Like a character from one of his novels, Osamu Dazai is remembered as a figure of intense romanticism, an image fuelled by his love suicide with a woman who was neither his wife nor the mistress with whom he had conceived a child. A proponent of the “I novel”, Dazai lived as he wrote, but crucially gives the hero of his final book, No Longer Human, a less destructive ending than he eventually gave himself in that he finally accepts his toxicity and chooses self-exile in the belief that he has fallen so far as to lose the right to regard himself as “human”. Mika Ninagawa’s biographical treatment of Dazai borrows the title from his most famous novel (人間失格 太宰治と3人の女たち, Ningen Shikkaku: Dazai Osamu to 3-nin no Onnatachi), but gives it a subtitle which pulls focus from the author himself towards the three women who each in their own way made him what he was.

Yet what he was, in Ninagawa’s characterisation at least, was hollow. Late into the film, she includes a famous literary anecdote in which a young Yukio Mishima (Kengo Kora) turns up to a party where Dazai (Shun Oguri) is holding court following the publication of The Setting Sun and accuses him of being a poseur, a coward who writes endlessly about death but has no real intention of following through. That’s something of which he was often accused, having already failed to die as we see in the film’s opening in a love suicide in which the woman died calling out another man’s name. Intensely insecure, he carps on about being disrespected by the literary establishment, in fact using his final days and one of his last chances to pen an embittered screed against the famous authors who read but apparently did not care for his work. His editor despairs of him, resenting him not only for the debauched lifestyle which interferes with his writing but his essential caddishness that sees him both mistreat his loyal wife and use countless women as fuel for his art never quite caring about what happens to them afterwards.

Dazai claims that Michiko (Rie Miyazawa), his legal wife and mother of his children, is OK with his affairs because it is “love in the service of art”. There is some truth in that, though as Michiko points out, Dazai himself would have no interest in a woman so passively self-sacrificing as that of Villon’s Wife. When the children catch sight of their father embracing another woman at a festival, she calmly tells them that he is “working” before pulling them on in embarrassment, putting up with it perhaps more because she has no other option than in respect for Dazai the great artist.

Yet as his new lover Shizuko (Erika Sawajiri) claims, beautiful art comes from broken people, an idea which perhaps enables Dazai’s grandiose vision of himself as an unjustly dismissed literary genius. Just as Villon’s Wife was “inspired” by his relationship with Michiko, The Setting Sun is about Shizuko, only this time Shizuko is more collaborator than muse. He plunders her diaries and the most famous line from his novel, “Men are made for love and revolution” was in fact not written by him but stolen from her (she eventually asks for a co-writing credit but evidently did not get one, penning her own book instead). What she asks him for in return is a child, a strangely common request also made of him by Tomie (Fumi Nikaido), the woman with whom he eventually dies largely, the film suggests, because despite the longing for life that birth represents she pulled him towards death and he was too indifferent to resist. Dazai’s resistance, if you can call it that, is listlessness in which he has no desire to live but equally perhaps no real desire to die.

Despite the foregrounding of the title, the three women are perhaps three paths he could take – the conventional as a husband and father, the radical as man standing equal with a woman who is not a wife with whom he births “a new art”, and finally the nihilistic “death” which is the route he eventually takes. With or perhaps for Tomie he writes the work he knows will destroy him in which he excoriates himself rather than her but, unlike in life, receives the gift of self-awareness and then lets himself (partially) off the hook. In Ninagawa’s visual complexity he is perhaps to an extent already dead, collapsing in the snow after haemorrhaging blood in the later stages of TB next to a red circle looking oddly like the flag of Japan only for white petals to begin raining down on him as if he were already in his coffin. We see repeated shots of shimmering water reminding us of his death by drowning, and for all of Ninagawa’s characteristically colourful compositions it’s the women who are surrounded by the vibrancy of flowers in full bloom never Dazai himself. On her husband’s death, Michiko can exclaim only (and ironically) that the sun has finally come out as she gets on with her life putting out the washing. Shizuko affirms that Dazai was the love of her life while asserting her own artistic identity in pushing her book which is an inversion of his. Meanwhile, Dazai has consumed himself, a cad to the last, overdosing on romanticism as an artist who fears he has nothing else to say.

Hong Kong trailer (English/Traditional Chinese subtitles)

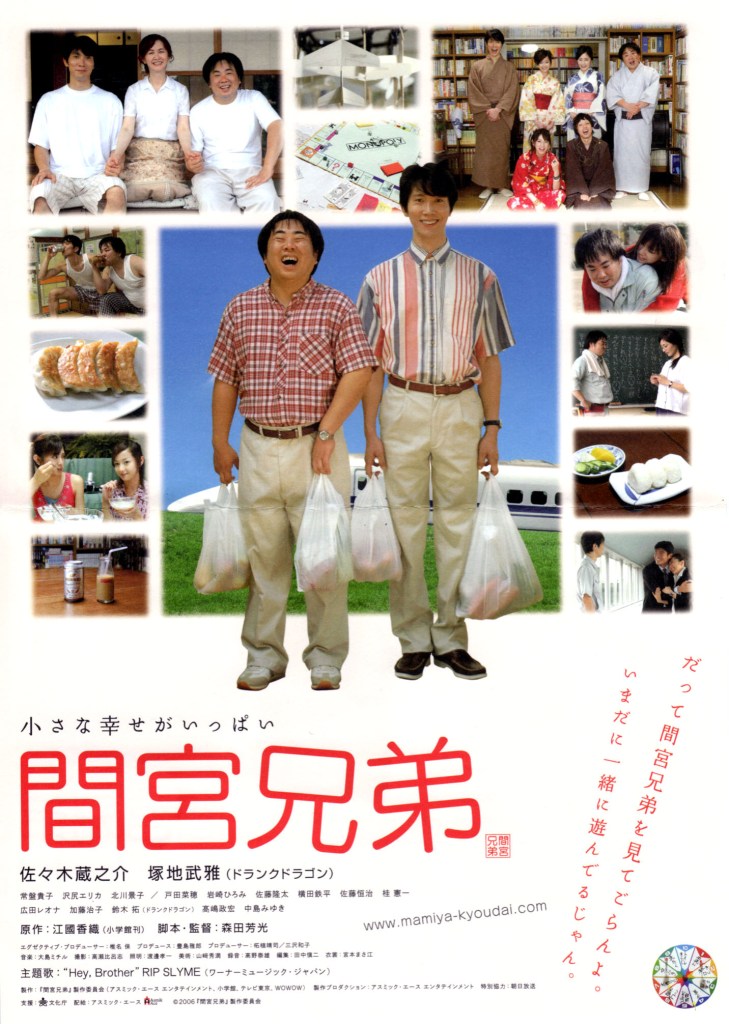

Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.

Ever the populist, Yoshitmitsu Morita returns to the world of quirky comedy during the genre’s heyday in the first decade of the 21st century. Adapting a novel by Kaori Ekuni, The Mamiya Brothers (間宮兄弟, Mamiya Kyodai) centres on the unchanging world of its arrested central duo who, whilst leading perfectly successful, independent adult lives outside the home, seem incapable of leaving their boyhood bond behind in order to create new families of their own.

Enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry Sion Sono has always been prolific but recent times have seen him pushing the limits of the possible and giving even Takashi Miike a run for his money in the release stakes. Indeed, Takashi Miike is a handy reference point for Sono’s take on Shinjuku Swan (新宿スワン) – an adaptation of a manga which has previously been brought to the small screen and is also scripted by an independent screenwriter rather than self penned in keeping with the majority of Sono’s directing credits. Oddly, the film shares several cast members with Miike’s Crows Zero movies and even lifts a key aesthetic directly from them. In fact, there are times when Shinjuku Swan feels like an unofficial spin-off to the Crows Zero world with its macho high school era tussling relocated to the seedy underbelly of Kabukicho. Unfortunately, this is somewhat symptomatic of Sono’s failure, or lack of will, to add anything particularly original to this, it has to be said, unpleasant tale.

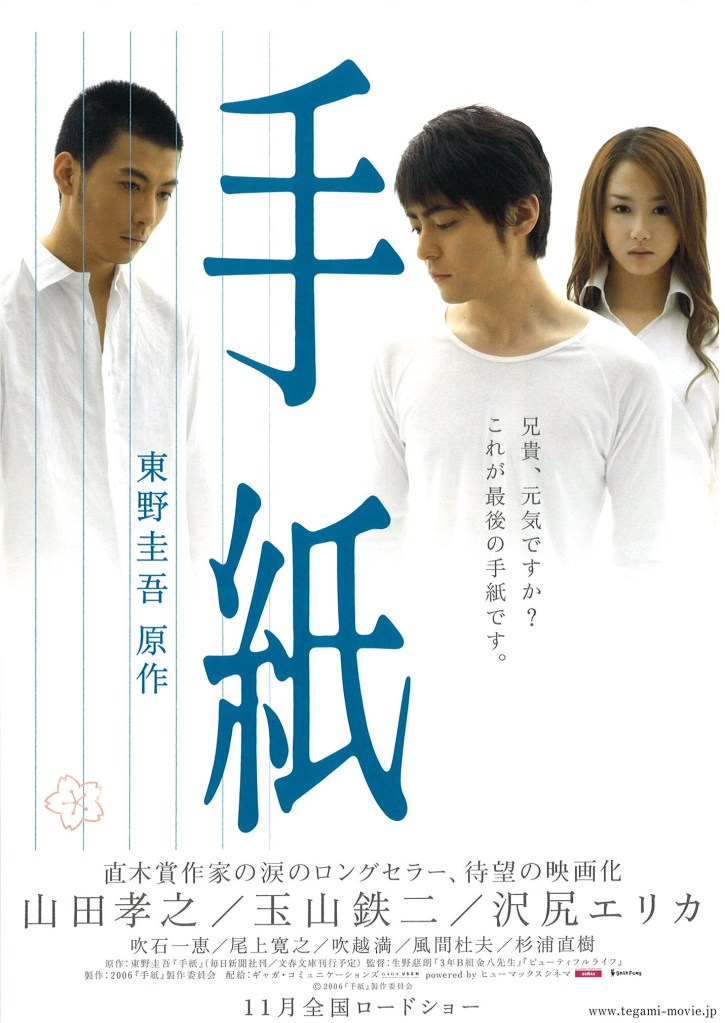

Enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry Sion Sono has always been prolific but recent times have seen him pushing the limits of the possible and giving even Takashi Miike a run for his money in the release stakes. Indeed, Takashi Miike is a handy reference point for Sono’s take on Shinjuku Swan (新宿スワン) – an adaptation of a manga which has previously been brought to the small screen and is also scripted by an independent screenwriter rather than self penned in keeping with the majority of Sono’s directing credits. Oddly, the film shares several cast members with Miike’s Crows Zero movies and even lifts a key aesthetic directly from them. In fact, there are times when Shinjuku Swan feels like an unofficial spin-off to the Crows Zero world with its macho high school era tussling relocated to the seedy underbelly of Kabukicho. Unfortunately, this is somewhat symptomatic of Sono’s failure, or lack of will, to add anything particularly original to this, it has to be said, unpleasant tale. When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.