A kind-hearted taxi driver becomes our guide to the post-war society in a cheerful omnibus movie co-scripted by Akira Kurosawa and directed by Senkichi Taniguchi, My Wonderful Yellow Car (吹けよ春風, Fukeyo, Haru Kaze). Inspired by a Reader’s Digest column titled “human nature as seen in the rearview mirror”, the film follows cheerful cabbie Matsumura (Toshiro Mifune) as he drives around Tokyo in 1953 picking up various fares and sometimes adding commentary or trying to help with whatever kind of problem seems to be bothering them.

Then again, he stays well out of the first fare’s business as a young couple have obviously had some kind of falling out. Bursting into tears, the girl (Mariko Okada) announces that she wants to postpone the wedding and maybe even rethink this whole thing, while the boy reiterates with slight irritation that he’s said he’s sorry with the implication that that should be the end of it though we have no idea what (if anything) he’s actually done. In any case, they eventually patch things up over some canoodling in the back seat and ask to be dropped off so they can get something to eat. In some ways, the young couple represent a more hopeful vision of post-war youth who have no apparent worries besides their tiff and are financially comfortably enough not only to be getting married but can afford to travel by taxi and pay for a meal on the same occasion.

Their situation is later contrasted with that of an older couple who’ve moved from Osaka to Tokyo in their old age and have bought a box of live lobsters to celebrate their silver wedding anniversary but as Matsumura notes though they appear to be quite well off they also seem somehow sad. That turns out to be because they lost their only son the previous summer and have moved into his old apartment. The old lady also cries in the back seat, but for a completely different reason. As they’ve only just moved here, they don’t have friends or anything to do and are completely lost in the wake of their son’s death. Matsumura’s kindness is demonstrated when he borrows three flowers from a bouquet delivered to a girl at the petrol station and presents them as an anniversary gift. The couple are so touched they invite him to enjoy their anniversary dinner with them and by the end of it have made the decision that they should go back to Osaka and restart their lives by re-opening their old business.

Throughout all this, Matsumura is very conscious of the meter. Every second he spent in the old couple’s apartment cost him money, but as he’s fond of saying you can’t always think of things like that. Even so, he reminds himself he has a wife and child so should be mindful of the clock but still turns down a fare to go back to the station and check on a young girl he’s pretty sure is trying to run away from home. A weird guy was sniffing around her and was in fact just about to lead her off when Matsumura gets back and announces he’s come to pick her up. Matsumura spends the rest of the ride trying to convince her to go home, repeatedly reminding her that most of the “panpans”, or streetwalking sex workers catering to US servicemen, were also once runaway girls. To more modern eyes we might wonder if sending her home is what’s best without knowing the reasons she wanted to leave. He goes so far as to buy her ramen which costs him more money on top of the lost fare which doesn’t collect from her either when he, a little less responsibly, abandons her when she refuses to tell him where she lives. Thankfully, it all seems to work out. The girl made a sensible decision to go home after all and is later seen happily doing her Christmas shopping with her mother who also thanks him for looking out for her.

Perhaps these kinds of altruistic acts of kindness explain why Matsumura’s own clothes are quite ragged with a hole in his jumper and a tear to the shoulder of his jacket. He’s driving the cab in straw sandals which apart from anything else is probably quite cold in the winter. He spends another afternoon giving a free ride to some children, about 15 of them, who’ve crowdfunded 100 yen because they’ve never been in a car before and want to go as far it’ll take them having no idea that 100 yen is actually the initial charge so you can’t go anywhere on it all. Of course, Matsumura ends up taking them a bit further, and then realises he’ll have to take them back to where they were because they won’t have any other way of getting there or of knowing where they are now.

On the other hand, sometimes he ends up with nuisance fares such as two drunk guys who keep singing their university song. One of them even climbs out of the window and up onto the roof, causing Matsumura to assume he’s fallen off somewhere and he’ll have to go back and look for him to make sure he’s not hurt only to find him burbling in the footwell. He also ends up getting hijacked by a crook with a gun on his way back from Yokohama but getting a telling off from the police rather than a thank you for catching him after unwisely taking hold of the gun himself and messing up all the fingerprints.

One might think the time he had a famous actress in the back of his cab who even sang along with the jingle he’d written for the cheerful yellow vehicle might make up for all that, but he says the story that best exemplifies why he loves driving a taxi is that of a middle-aged couple he picked up at the harbour shortly after a boat had docked repatriating people from China. Even in 1953, some had not yet returned after becoming trapped by the Chinese Civil War and eventual Communist victory. The man is dressed in military uniform and says he’s just been demobbed when Matsumura asks him, trying to lighten the mood while there’s obviously some degree of tension between the man and his wife. But as we gradually come to understand, it’s all just a ruse and he has in fact been in prison in Japan for the last seven years for an unspecified crime.

His wife asks Matsumura to drive around the city and attempts to show him how much things have recovered, suggesting that they can now put the past behind them and start over. But the man remains sullen and grumpy. He’s afraid to go home, afraid to face the neighbours worrying if they know what he did and that he’s been in prison. But most of all he’s afraid to face his children, the youngest of which he’s never met. The kids have been teaching themselves to say “Welcome home, Daddy,” in Mandarin believing he’s been in China all this time which the wife has to explain before they get there. The man tells his wife he understands if she doesn’t want him back, but she assures him that the children are excited as is she to start their new life together. Nevertheless, though they’ve been eagerly practicing, the older two children simply freeze when confronted by this anxious stranger who turns around to leave again feeling as if he doesn’t have the right to come back here after all only for the youngest one to suddenly pipe up with the phrase note perfect. It’s this kind of scene, getting people to where they need to be physically and emotionally, that seems to make Matsumura’s job worthwhile. In essence, he’s ferrying people towards the cheerful post-war future his cute yellow cab represents while driving round the rapidly changing city wondering who it is that’s going to end up in the rearview mirror today.

Title song (no subtitles)

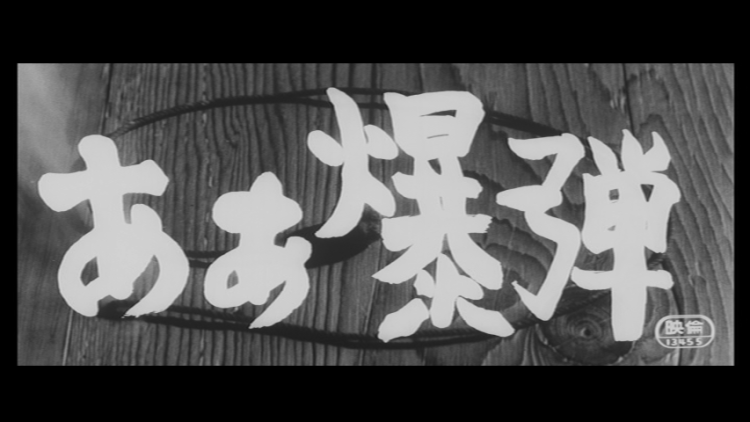

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.