A feckless gambler gets a final shot at redemption when he’s suddenly asked to take care of an autistic son he never knew he had in Anthony Pun Yiu-Ming’s nostalgic drama, One More Chance (別叫我”賭神). Previously titled “Be Water, My Friend”, the film has had a troubled production history only reaching cinema screen four years after filming concluded in March 2019 and has been retitled in the Chinese “Don’t Call Me the God of Gamblers” which seems to be a blatant attempt to cash in the audience’s fond memories of similarly pitched Chow Yun-fat vehicles from the ’80s and ’90s such as All About Ah Long.

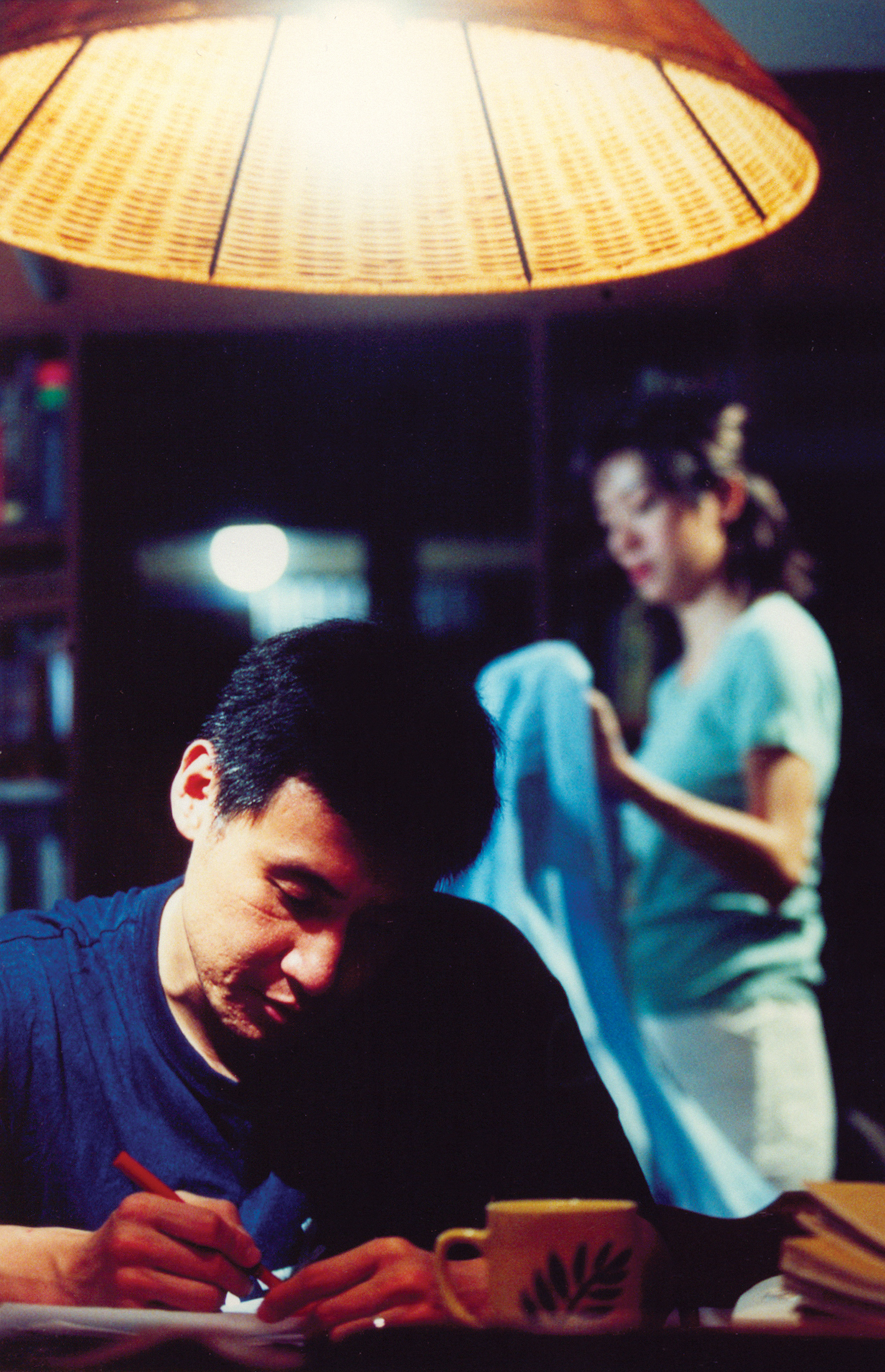

In truth, Chow is probably a little old for the role he’s cast to play as the middle-aged barber Water who’s long since fled to Macao in an attempt to escape problems with loansharks caused by his gambling addition. Of course, Macao is one of the worst places someone with a gambling problem could go and so Water is already up to his neck in debt and a familiar face at the local casino. That’s one reason he ends up going along with the proposal of old flame Lee Xi (Anita Yuen Wing-Yee) to look after her grownup son, Yeung (Will Or Wai-Lam), who is autistic, for a month in return for 50,000 HK dollars up front and another 50,000 at the end assuming all goes well. She claims that Water is Yeung’s father and even provides forms for him to send off for a DNA test if he doesn’t believe her, but at this point all Water is interested in is the cash.

To begin with, he pretty much thinks of Yeung as cash cow, descending on a Rain Man-esque path of using him to up his gambling game but otherwise frustrated by his needs and ill-equipped to care for an autistic person whom he makes little attempt to understand. For his part, Yeung adapts well enough and tries to make the best of his new circumstances but obviously misses his mother and struggles when Water selfishly disrupts his routines. For all that, however, it’s largely Yeung who is looking after Water, tidying the apartment and bringing a kind of order into his life while forcing him to reckon with the self-destructive way he’s been living.

Picking up a casino chip in the opening sequence, Water describes it as a “chance” in an echo of the way he’s been gambling his life just as he decides to gamble on taking in Yeung. At one point, he wins big on the horses but takes his winnings straight to the casino where he’s wiped out after staking everything on a single bet only to realise he’s been played by another grifter at the table. It seems that Xi left him because of his gambling problem and the resultant change in his lifestyle that had made it impossible for her to stay or raise a child with him, causing Water to become even more embittered and cynical. Where once he provided a refuge for wayward young men trying to get back on the straight and narrow, now he’s hassled by petty gangsters over his massive debts.

Nevertheless, it’s re-embracing his paternity that begins to turn his life around as he bonds with Yeung and begins to have genuine feelings for him rather than just fixating on the money while simultaneously recognising that Yeung is already a man and able to care for himself in many more ways than others may assume. One could say that he gambles on the boy, staking his life on him rather than endless rolls of the dice to fill an emotional void but also rediscovering a sense of himself and who he might have been if he had not developed a gambling problem and left it up to chance to solve all his problems. Unabashedly sentimental, the film flirts with nostalgia in the presence of Chow and Anita Yuen and largely looks back the Hong Kong classics of the 80s and 90s if with half an eye on the Mainland censors board, Bruce Lee shrine not withstanding, but nevertheless presents a heartwarming tale of father and son bonding and paternal redemption as Water crosses the desert and finally reclaims himself from his life of dissipation.

Original trailer (English subtitles)