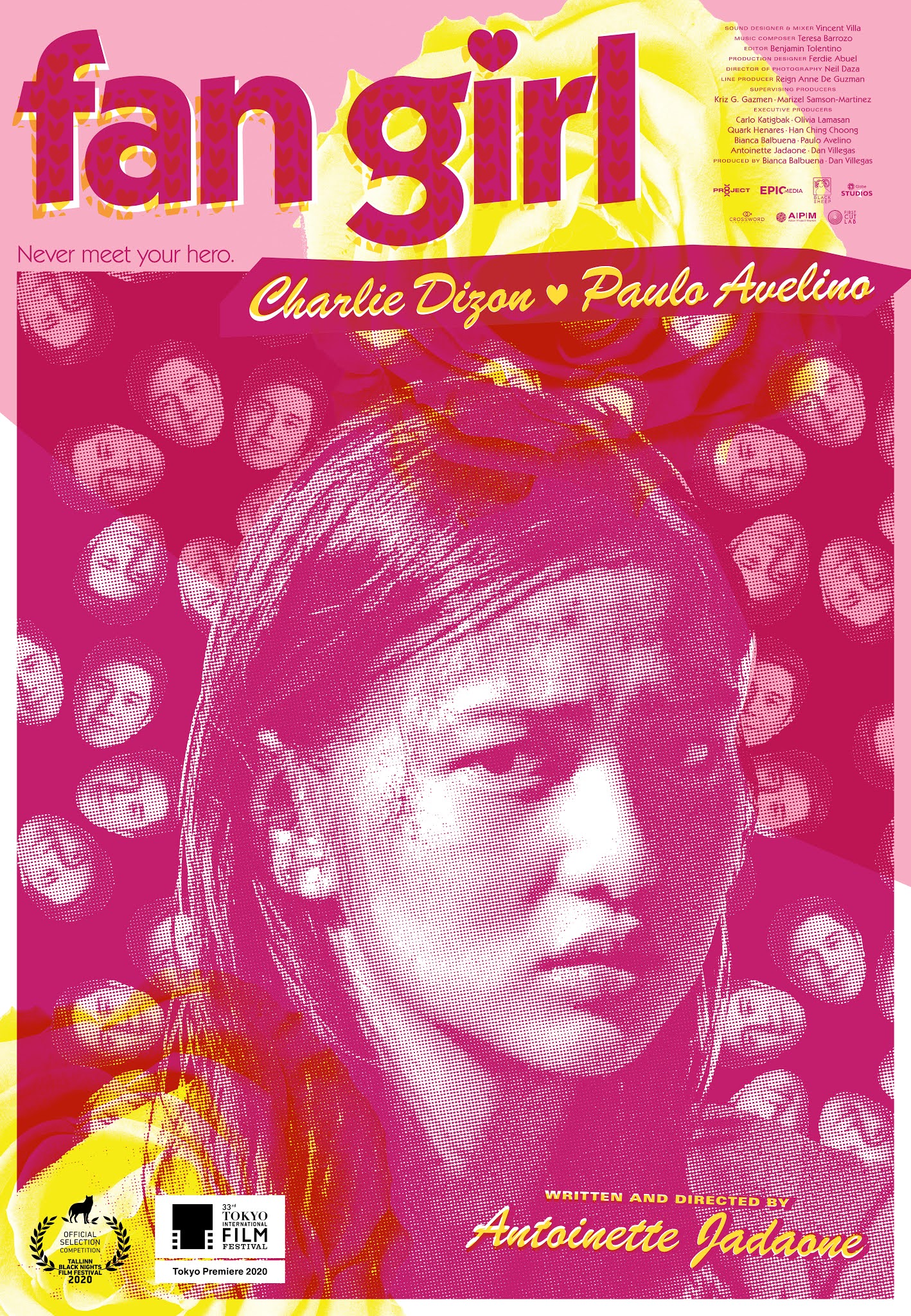

Never meet your heroes is the conventional wisdom, and for good reason in that nobody’s perfect and when you place someone on a pedestal they can’t help but disappoint you when they step down. For the heroine of Antoinette Jadaone’s Fan Girl, however, the clash between her youthful escapist delusions and the ugly truth that lies behind them is more than just a cautionary tale about the commodification of the human image exposing the unpleasant duplicities of a fiercely patriarchal, misogynistic society that those escapist images both mask and reinforce.

16-year-old Jane (Charlie Dizon) is completely obsessed with rom-com star Paulo Avelino (playing a heavily fictionalised version of himself), bunking off school to attend a publicity event at a local mall at which he and his co-star Bea Alonzo (also playing “herself”) with whom he is apparently in a real relationship are set to appear to promote their latest movie. In the ensuing crush, Jane manages to slip away from the crowd and stowaway on a pickup truck that improbably enough belongs to Paulo who will be driving himself away from the event. Excited in her illicit adventure, Jane snaps candid picks of her crush peeing on the roadside scandalised by the realisation that she’s glimpsed his intimate area, zooming in on her pic while messaging her friend to share the news that Paulo is “a biggie”. Soon after, however, she falls asleep and when she wakes up it’s already dark. The truck has arrived at a creepy gothic mansion out in the country. She thinks she sees Paulo beckon her inside and jumps the gate, only the figure she spots on the upstairs balcony doesn’t match the idea of the romantic prince in her mind nor is he very excited to see her.

To begin with, perhaps our sympathies are all with Paulo unwittingly stalked by this obsessive teenage fan who’s already invaded his privacy and feels herself entitled to his attention solely because of her devotion towards him. Yet we also fear for her, in the beginning at least Paulo is careful to rebuff her youthful romantic feelings and shows no signs of taking advantage of a naive teenager in the way some other stars might. In this situation of mutual threat, we can’t be sure who is most in danger, the vulnerable star struck fan or famous actor pursued by crazed stalker.

Nevertheless, Paulo is quickly stripped of his star appeal, his gentlemanliness undercut by his constant insistence that “this can’t get out” eventually knocking Jane’s phone out of her hand as she takes a selfie next to his sleeping face lest she post it online and cause a scandal. As soon as he climbs inside his pickup truck he begins to shed his star persona, wiping the makeup from his face complaining they’ve made him look “like a faggot”, pausing only when stopped by police who immediately let him off after getting him to sign one of the many posters he has on hand for their lovestruck teenage daughter at home. Sitting in the back Jane can perhaps hear his constant swearing, but it doesn’t seem to penetrate. When she calls out his name in the villa she finds him shirtless, slightly pudgy with a lewd tattoo of a cobra woman on his back, his long hair greasy as he snorts cocaine from his curled fist.

Paulo appears to live in the mansion but its gates remain permanently locked as if he doesn’t carry the key while the place is almost devoid of furniture, creepy its dusty emptiness. Perhaps it in a sense reflects his sense of self, somewhat hollow and ill-defined. Unravelling throughout his night with Jane he hints at a sense of impotence and despair, that he’s a slave to his image and in a sense no longer exists. The image Jane has of “Paulo Avelino” is entirely created by the marketing department, as is his apparently fictitious relationship with Bea, while he inhabits this shabby castle like a moody vampire apparently in love with a local woman who bore his child but is married to someone else. His lover later complains he treats her “like a whore”, stopping by only when he feels lonely or unfulfilled but apparently unready or unwilling to take real responsibility.

Nevertheless, the scales do not fall from Jane’s eyes for quite some time. We gradually realise that her warm romantic fantasies are a displacement activity masking her fear and her sorrow over all the men who have already betrayed her. We might ask if her mother isn’t wondering where she is, but she later calls only to complain about her abusive boyfriend who hasn’t returned home fearing he is with another woman. Jane recalls seeing her estranged father who abandoned her with his new family, perhaps reflecting on Paulo’s complicated familial situation while clinging fiercely to the image of “Paulo Avelino” from the movies, a sensitive, romantic man who’s not afraid to cry. But underneath it all the real Paulo is just as much a product of toxic masculinity as any other man, a closet misogynist who thinks all women are “whores” and reacts with violence when his authority is challenged.

Jane keeps insisting that she isn’t a kid anymore, consciously acting older drinking and smoking to perform the role of a mature woman, but finally comes of age only when all her illusions are shattered realising that Paulo is just another violent, abusive, man child resentful of his own insecurities. Returning home she surveys her pinups of him with a sense of regret, now denied even this small refuge of fantasy from the realities of her existence. Yet now she truly is no longer a child, angry but also realising that she doesn’t have to simply accept it in the way her mother has done resolving to seize her own agency though it remains unclear what kind of consequences if any her act of resistance may eventually provoke. A dark exploration of the interplay between fan and idol, the duplicities of image, and the persistent harm of an authoritarian patriarchy as evoked by the ubiquitous Duterte posters, Antoinette Jadaone’s nuanced drama paints a bleak portrait of the contemporary society but ends perhaps on a brief note of hope if also of tragedy as Jane smokes her cigarettes, not a kid anymore.

Fan Girl streams in the US until May 2 as part of San Diego Asian Film Festival’s Spring Showcase.

Original trailer (English subtitles)