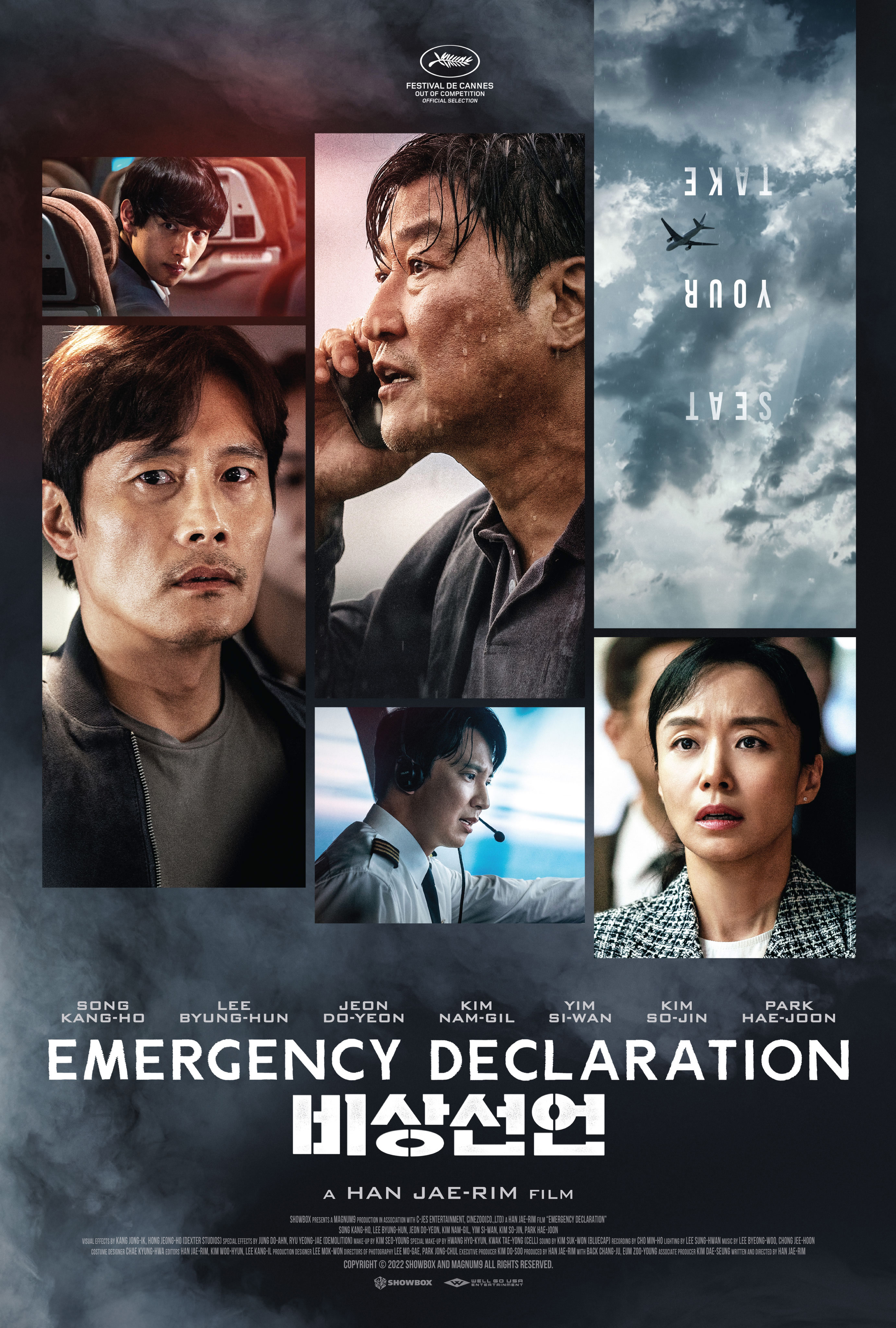

“Disasters are arbitrary” admits a pundit commenting on a potential air disaster, “people became victims for being in a certain place at a certain time”. “We were caught in a disaster that none of us wanted” the pilot later echoes while explaining that they have chosen to exercise what little control is left to them in making their own decision as to how they intend to deal with the hand that fate has dealt them. Han Jae-rim’s Emergency Declaration (비상선언, Bisang Seoneon) harks back to classic disaster pictures of the 1970s such as genre archetype Airport but also meditates on Korea’s place in the contemporary global order along with the rights and wrongs of exercising one’s own judgement when it goes against all practical advice.

The disaster in this case begins with a mad scientist, Ryu (Im Si-wan), who decides to kill as many people as possible along with himself by releasing a deadly virus he tweaked to make even more lethal aboard a commercial airliner. Later it’s suggested that Ryu had some kind of breakdown after the death of his mother, also a microbiologist, who had a domineering influence on his life which does seem to play into an uncomfortable trope of blaming the mother for everything that goes wrong with a child though Ryu’s resentment is in part towards the pharmaceuticals company he claims fired him unfairly. As in many recent Korean films, a strong undercurrent of anti-Americanism runs throughout, the international pharmaceuticals company with an American CEO refusing to assist the Korean police’s inquires not wishing to admit that they illegally procured a deadly virus from the Middle East and then allowed Ryu to get hold of it illicitly. This also of course means that they are slow to grant access to a potential antidote/vaccine despite carrying both. Meanwhile, the plane is later turned back from Honolulu and prohibited from landing anywhere on US territory because of the uncertainty surrounding the infected on board.

The plane in effect becomes a kind of plague ship that takes on additional significance during an era of pandemic. Having been rejected by the US, the plane tries to land in Japan but is also refused permission and later threatened by the Japanese Self Defence Forces who even open fire on it and threaten to shoot the plane down if it does not leave Japanese airspace. The official response is more nuanced than it had been with the Americans, a politician expressing his regret and sympathy with the people of Korea but also emphasising that their responsibility is towards the people of Japan and that as they cannot be sure the treatment will work on Ryu’s mutated variant, they cannot allow the plane to land. As the opening titles explain, an Emergency Declaration is a sacred aviation rule that means no one should be refusing them help, yet they do begging the question of what it really means if in the end the authorities can just choose to ignore it.

But then again, it seems that not even Korea is fully onboard with accepting the plane back onto Korean soil. With news quickly spreading via social media, mass protests erupt from those who brand it a “biochemical missile” and would rather it be shot down than risk contaminating the wider population while counterprotests insist that there are many Korean people onboard and it’s only right that they be allowed to return home and be cared for by the authorities. The authorities are however torn, unwilling to admit they’re considering simply allowing 150 people to die for the greater good leaving only the Transport Minister (Jeon Do-yeon) to exercise her own judgement in arguing for the plane landing with quarantine procedures in place.

Former pilot Jae-hyuk (Lee Byung-hun), a passenger on the flight with his little girl who suffers from eczema, is later tasked with exercising his own judgement in deciding whether to land the plane at a closer airport he feels is safer or try to hold out until the destination recommended by the authorities despite dwindling fuel supplies. The plane disaster is Jae-hyuk’s redemption arc allowing him to overcome past trauma in having made a similar decision before which led to the deaths of two cabin crew thanks to the selfishness of passengers who blocked exits trying to retrieve their luggage before escaping. One thing that wasn’t so much of an issue in the ’70s is that passengers are now able to receive information in real time via their phones thanks to onboard wireless, meaning that they learn all about the virus, the cure, and that the cure might not work independently giving rise to even more chaos and confusion and presenting a serious threat to traditional disaster management techniques. Nevertheless, they too eventually exercise their own judgement in coming to the conclusion that perhaps it is better if they choose not to land rather than risk infecting their friends and family.

The passengers on the plane do not blame those on the ground accepting that they are simply afraid. “You can’t just save yourselves” a particularly paranoid passenger is fond of saying completely oblivious to the fact that’s what he’s been trying to do with a pointless insistence in segregating the infected aboard a plane that exclusively uses recycled air only to completely reverse his thinking on hearing the plane may make an emergency landing in which case the rear of the plane, where the infected are, is safer. It is in the end a radical act of self-sacrifice by a policeman on the ground (Song Kang-ho) that paves the way to a happier solution for all but could just as easily have turned out differently. Disasters are arbitrary after all, at least as long as you aren’t the one causing them. Counterintuitively, the message may be that your government might not help you and others certainly won’t, but if you’re making your own emergency declaration you have the right to exercise your own judgement in the knowledge that either way you’ll have to answer for your decision.

Emergency Declaration is released in the US on Digital, Blu-ray, and DVD on Nov. 29 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Clip (English subtitles)

Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but such power is often a matter more of faith than actuality. Coming at an interesting point in time, Han Jae-rim’s The King (더 킹) charts twenty years of Korean history, stopping just short of its present in which a president was deposed by peaceful, democratic means following accusations of corruption. The legal system, as depicted in Korean cinema, is rarely fair or just but The King seems to hint at a broader root cause which transcends personal greed or ambition in an essential brotherhood of dishonour between men, bound by shared treacheries but forever divided by looming betrayal.

Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but such power is often a matter more of faith than actuality. Coming at an interesting point in time, Han Jae-rim’s The King (더 킹) charts twenty years of Korean history, stopping just short of its present in which a president was deposed by peaceful, democratic means following accusations of corruption. The legal system, as depicted in Korean cinema, is rarely fair or just but The King seems to hint at a broader root cause which transcends personal greed or ambition in an essential brotherhood of dishonour between men, bound by shared treacheries but forever divided by looming betrayal.