The Wicked Priest returns for a second instalment but once again finds himself confronted with imperfect paternity in The Wicked Priest 2: Ballad of Murder (極悪坊主 人斬り数え唄, Gokuaku Bozu: Hitokiri Kazoe Uta). This time directed by Takashi Harada, the series begins to embrace its anarchic nature in the sometimes cartoonish exploits of its hero who largely just wants to have a good time but is inconveniently called to missions of justice while silently stalked by ghosts of the past in the form of spooky monk Ryutatsu (Bunta Sugawara) whom he blinded in a fight at the end of the previous film.

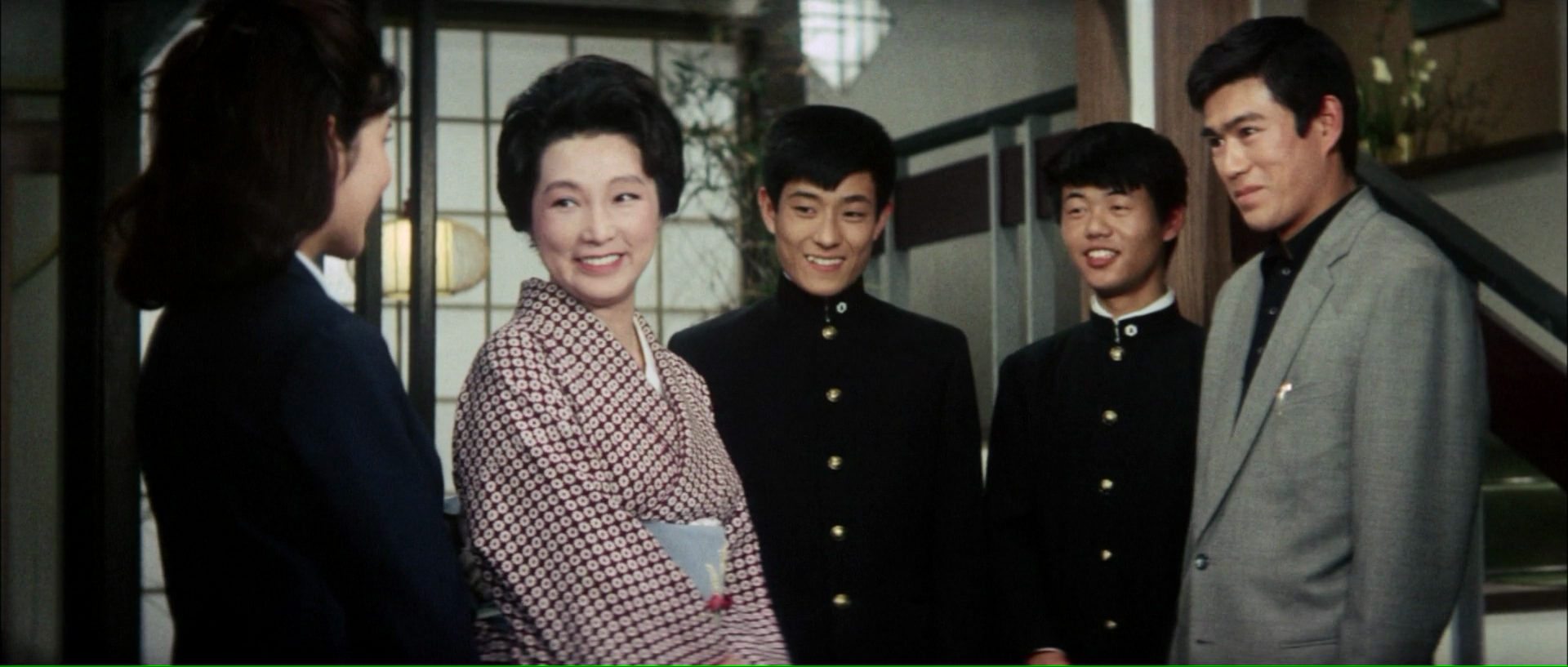

Now a lonely wanderer, Shinkai (Tomisaburo Wakayama) comes across a fleeing yakuza with a small boy in tow and steps in to help. As he discovers, the man, Rentaro (Asao Koike), is a former gangster whose wife has passed away leaving him the sole parent to Seiichi, a little boy of around six. Rentaro wants to turn himself in to the police so he can fully sever his ties to the underworld and start again along a more honest path to raise his son right, but needs to deliver him to his father, a jujitsu instructor, before he can. Somewhat surprisingly, Rentaro suddenly asks Shinkai, a man he’s never met before, to take Seiichi to his grandfather before rushing off supposedly to give himself over to justice. When Shinkai arrives, however, Iwai (Hideto Kagawa), the grandfather, refuses to let them in having disowned his son over a local scandal some years previously.

As in the first film the major theme is paternal disconnection, Rentaro caught between wanting to be a good father to his son and seeking his own father’s approval. Fatherless himself, Shinkai cannot understand nor condone Iwai’s stubbornness in refusing even to look at his small grandson but resolves to care for him himself until his grandfather changes his mind or for as long as he is needed. Meanwhile it turns out that Rentaro was once involved with the evil gang, Godo, who have been causing trouble in the town by trying to muscle on the local cockfighting scene.

Godo have also been force recruiting some of the local men to increase their dominance while schmoozing with a corrupt politician, Kadowaki (Hosei Komatsu), hoping to make cockfighting a local speciality, even going so far as to kidnap a young woman known to Shinkai and gift her to him. Shinkai manages to rescue her after dressing up as a head priest and subtly suggesting to Kadowaki that his election prospects might suffer if any rumours were to get out about untoward goings on in his household. Iwai explains that jujitsu is not meant to be a violent art used to tackle evil gangsters but is anyway posited as a kind of local resistance leader standing up to Godo but with little effect other than making himself a target for their ire while left vulnerable in their ability to use Rentaro against him.

While getting mixed up in a local dispute trying to stand on the side of the little guy while looking after Seiichi, Shinkai’s exploits are often comedic in nature as he continues to play the part of the ironic monk though with real sincerity. Sneaking into a temple and belatedly discovering it to be a convent he becomes captivated by a Buddhist nun who appears to experience some kind of sexual awakening but then becomes fixated on him, insisting on becoming his wife and causing him to hide in a chicken coop to avoid her. On the other hand, his stalking by Ryutatsu takes on an almost spiritual quality as the near silent monk, now even more gaunt than before, shuffles his way towards him. Yet this Ryutatsu is a little more spiritual than before, agreeing to postpone his quest for vengeance unwilling to fight Shinkai with little Seiichi looking on and even at one point stepping in to protect him himself because all children are Buddha. Nevertheless, the film ends with another bloody battle surprising in its intensity with severed limbs and sudden violence as Shinkai ensures that those in the wrong get what’s coming to them, speeding up the wheel of karma by a turn or two to make sure they face justice, of one sort of another, in this world if not the next.