Vengeful ghosts in Japanese cinema usually originate from some kind of injustice. Generally, they’ve met a bad end through no real fault of their own while the person who killed them continues to prosper, though it’s also true that becoming a vengeful ghost means becoming an embodiment of vengeance which is itself indiscriminate and directed towards an unjust society more than one particular transgressor. In The Ghost of Kasane, for example, the curse extends to target the murdered man’s own daughter rather than just the descents of the man who murdered him.

Loosely based on the same tale, Curse of the Blood (怪談残酷物語, Kaidan Zankoku Monogatari) is indeed rooted in an injustice, but the emotions that create the ghost are greed and pettiness much more than a desire for retribution. A hatamoto lord has borrowed a large sum of money from a blind masseur evidently running a sideline as a loan shark. The monk, Sojun (Nobuo Kaneko), points out the term is coming to a close and the money should be repaid but Shinzaemon (Rokko Toura) doesn’t want to pay. Having just watched Sojun give his wife Toyo a sexually charged acupuncture session, he coldly remarks that he’ll be paying with his wife’s body. Toyo is obviously not really onboard with this plan, while Sojun at first declines only for Shinzaemon to state that he has the husband’s permission so it’s all fine. But Sojun then attempts to pay Shinzaemon with the improbably large sum of money he’s currently carrying, agreeing to sleep with Toyo but stating that the debt and interest will remain unchanged.

In any case, as soon as Sojun begins caressing his wife’s body Shinzaemon brutally cuts him down. He asks his recently returned grown up son Shinichiro (Masakazu Tamura) to help him dump the body in a nearby lake. Shinichiro complies, but it soon becomes evident that he disapproves of his father’s debauched ways and treatment of his mother. Despite being in debt to Sojun, Shinzaemon has a mistress and an illegitimate child with another woman he is also raising in his house. Shinichiro is painted as the good samurai son, one who behaves with the proper decorum and is unlike his father in his sense of righteousness. Shinzaemon even says as much, urging him to study Confucius and martial arts to one day restore the family he has ruined through his moral transgressions.

But in taking a sword to the mistress, Shinichiro is himself corrupted. She merely seduces him and it seems to be this that pulls him over to the dark side. Some years later, Shinichiro becomes a bandit, conman, and murderer accidentally killing a woman during rough sex and then running off with the stash of gold from the home of the man who had taken him and promised him a respectable future. Then again, the man had run a pawn shop so perhaps he was’t as morally upright as he might seem despite his kindness to Shinichiro while it also transpires that he was extracting sexual favours from the maid, Ohana (Yukie Kagawa), who turns out to be one of Sojun’s two daughters.

In another strange twist it was Ohana and her sister Suga (Saeda Kawaguchi) that Sojun had cursed when he died. He blamed them for somehow orchestrating his death and was insistent he was taking his money to hell with him, so they couldn’t have any of it. Suga takes him to task, decrying that he wasn’t fit to be a father and tormented their mother to death while otherwise complaining that he’s a sleazy old miser who doesn’t share his wealth with them so she’s taking it and running away. Suga’s determination to take the money is an attempt to seize autonomy, but she ends up using it in much the same way as her father, essentially as means of buying sexual companionship. Unbeknownst to her, she becomes besotted by Shinzo (Yusuke Kawazu), Shizaemon’s now grown-up illegitimate son, and binds him to her through her wealth.

Just like Shinichiro, Shinzo has been corrupted by the world around him and has little sense of humanity or morality. As he says, you’d have to be a fool to be honest in this world. Like his brother he has a caustic voiceover stating what he really thinks in contrast to his meek and obedient exterior, decrying Suga as an ugly old hag and expressing disgust at the idea of sleeping with her but also a willingness to put up with it in order to get his hands on her gold. Money lies at the root of all problems, but less so the need for it than simple greed. Shinzo has unwittingly entered a more romantic sexual relationship with Ohisa (Hiroko Sakurai), who turns out to be his half-sister, but her material desires outweigh his own and they are unable to move forward with their lives because they lack the economic stability to set up home.

To that extent, money is a means of overcoming the barriers of social class or gender to pursue greater freedom that inevitably becomes a means in itself. Sojun does not appear often as a ghost but haunts all the same, an evil smile on his face each time he manifests and takes pleasure in the sight of those who robbed him of his wealth paying the price. Simply put, he remains jealous of his money and can’t bear the thought of anyone else having it so is determined to drag it all the way to hell. Shinzaemon may have cursed his family through his immoral behaviour, but Sojun is simply annoyed about the money. Then again, perhaps he’s just a product of the world in which he lives in which money is the only way to overcome the oppressive barriers of disability, social class, and gender for to be without it is to be a lonely ghost with no currency or agency in society ruled by a fiercely patriarchal hierarchy. Hase conjures some haunting ghost imagery and uses bouts of solarisation as if the world itself were being bleached by all this cruelty and cynicism, occasionally isolating each of the protagonists in a theatrical spotlight which doubles as a personal hell yet in the end suggesting that there really is no escape from the vengeful haunting of an unjust society.

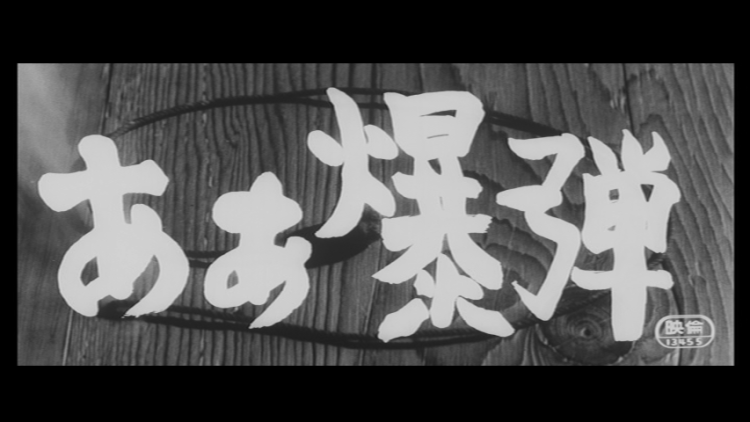

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.