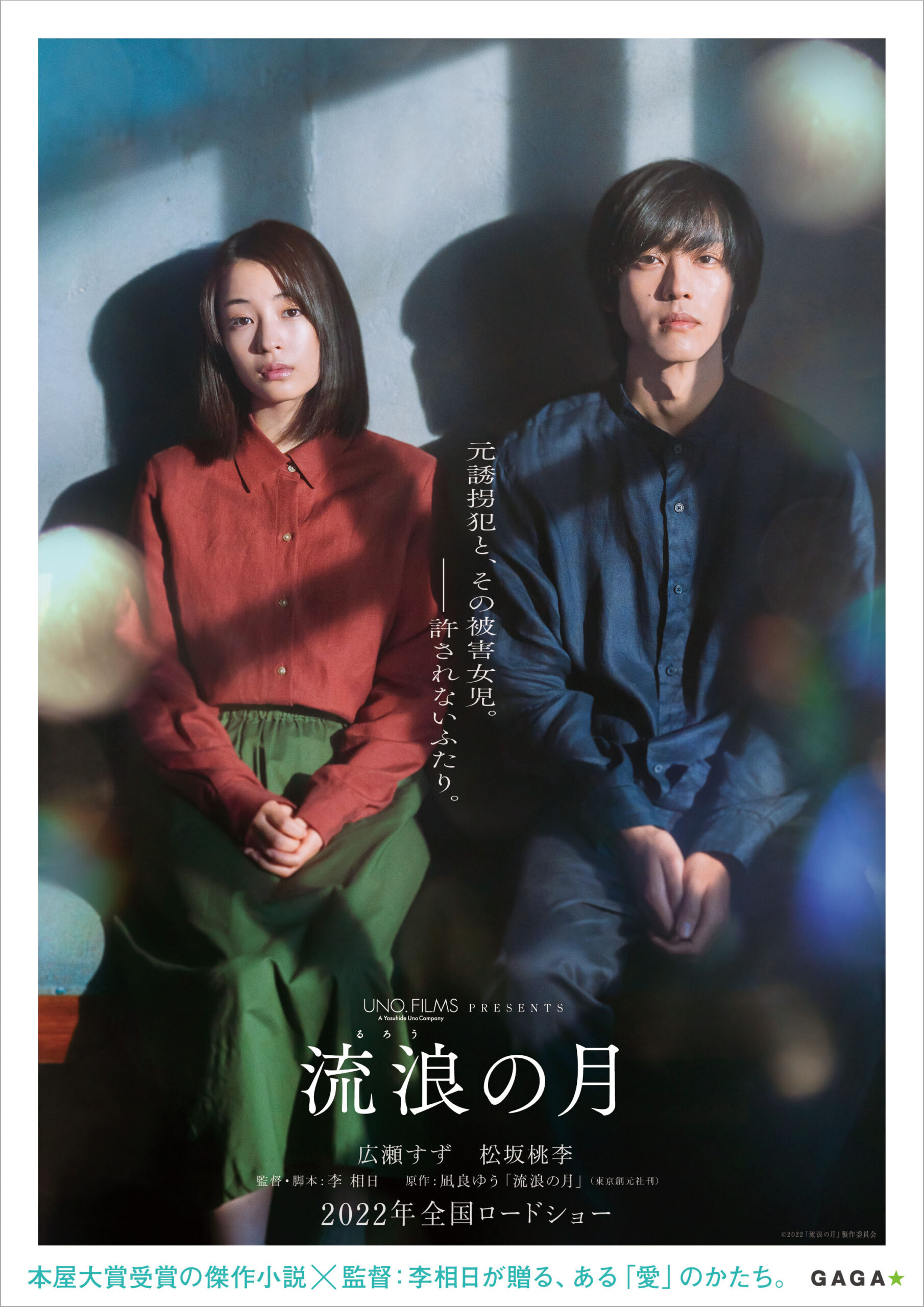

The fact that “people only see what they want to see”, as one character puts in Wandering (流浪の月, Rurou no Tsuki), has a been a minor theme in the work of Lee Sang-il for whom nothing is ever really as black and white as it might seem. Adapted from a novel by Yu Nagira, the film asks some characteristically difficult and necessarily uncomfortable questions while otherwise contemplating the toxic legacy of parental abandonment and the cycle of abuse.

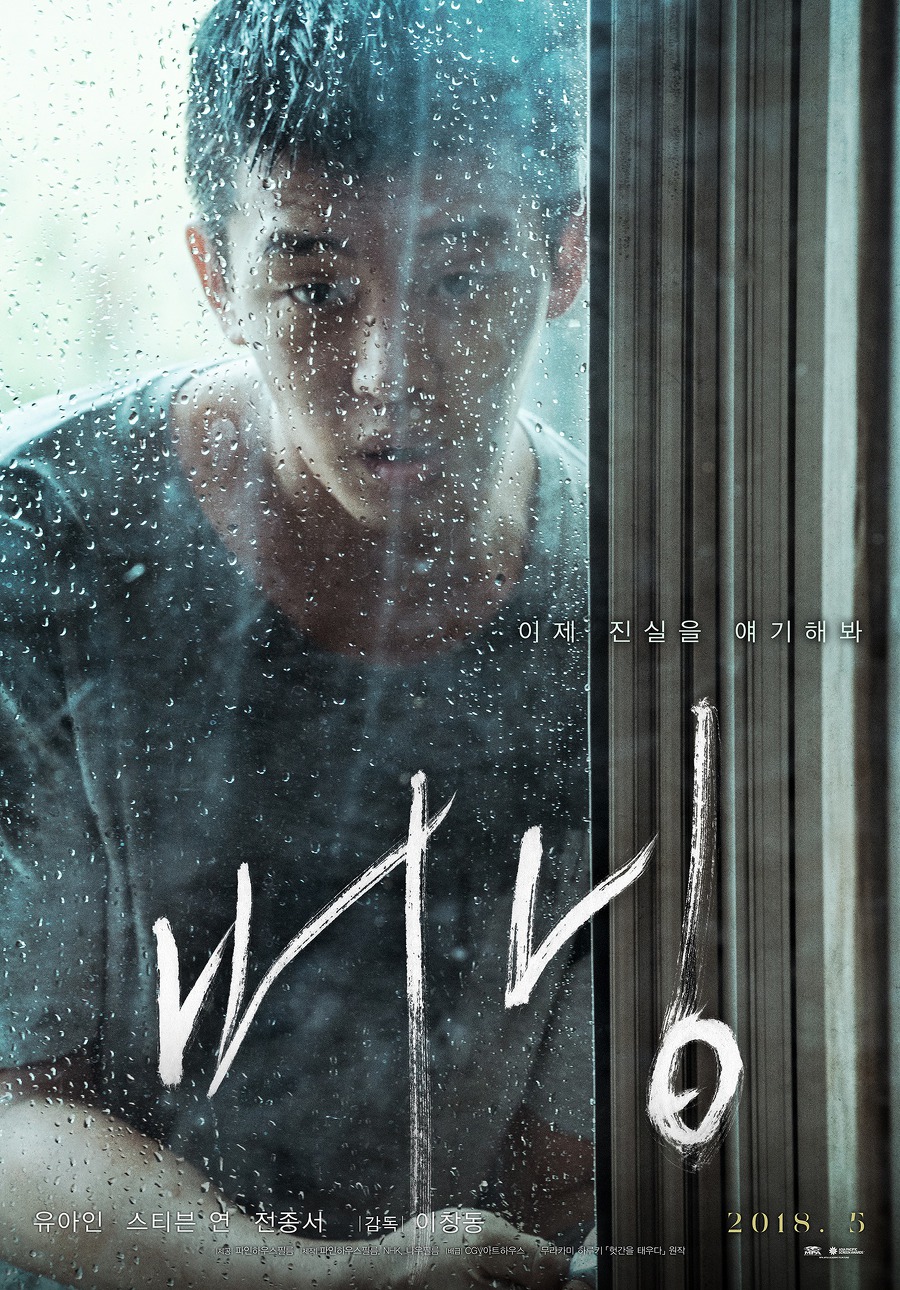

On a rainy day in 2007, a 19-year-old student, Fumi (Tori Matsuzaka), extended an umbrella to a lonely nine-year-old girl, Sarasa (Tamaki Shiratori), sitting out in the rain because she didn’t want to go home. He invites her to come back to his place and she agrees, later asking him if she can stay which she does for a couple of months until the police tear her away from Fumi’s side after tracking them down to a local lake. Fifteen years later, Sarasa (Suzu Hirose) has a job at a diner and is engaged to successful salaryman Ryo (Ryusei Yokohama) but though her life may look superficially perfect there are deep-seated cracks in the foundations. Ryo is a brittle and volatile man who is controlling and possessive, though Sarasa can’t seem to decide if she ought be “grateful” for the life she has or find away to break of Ryo before it’s too late.

Many of Ryo’s problems are apparently a result of latent trauma caused by his mother’s abandonment. Shortly before paying a visit to his family, Ryo had become violent with Sarasa and though his family notice the bruises they choose to say nothing until his sister, less out of compassion than a kind of spiteful gloating, explains that he’s done this sort of thing before and often picks vulnerable young women with disordered familial histories in the knowledge that it will make it much more difficult for them to leave. Sarasa had herself been abandoned by her mother who palmed her off on an aunt after her father’s death from cancer to run off with another man. The irony is that Fumi is accused of kidnapping her but is the only person to have shown her kindness while giving her the confidence to reassert her autonomy. Nevertheless he is branded a paedophile, while the relative who had sexually molested her while she was living with her aunt is allowed to go free.

Then again, it seems that Fumi does, in fact, have an attraction to young girls though he never behaved in a harmful way towards Sarasa and appears to have taken her in for otherwise altruistic reasons. The film asks the uncomfortable question of how we should respond to a person who identifies themselves as a paedophile but knows that to act on it would be wrong and therefore does not do so. Lee often frames Fumi in Christ-like fashion, cutting to his bare feet on the water of the wooden pier and later in the closing scenes catching him in a crucifixion pose with his legs slightly bent and his arms outstretched all of which emphasises his suffering and mental anguish in being afflicted with these unwelcome desires which after all he did not ask to be burdened with.

But this framing is further complicated by a final revelation that Fumi is suffering with a medical condition that prevented him from passing through puberty. His body is therefore not sexually mature and he feels himself to be, in this sense, a “child”. Most often what he says is that he is someone who cannot love an adult woman, which is most obviously a way of articulating that he cannot fulfil the sexual dimensions of an “adult” romantic relationship. Sarasa, meanwhile, comes to feel something much the same, explaining that she does not enjoy physical intimacy because of the trauma of her abuse which is recalled to her in Ryo’s aggressive and one-sided love making.

These are not distinctions which occur either to the police or the gutter tabloid press. The young Fumi had tried to explain to the detectives that Fumi had not harmed her, but they didn’t listen, while the pair later become fodder for malicious gossip when they re-encounter each other by chance and it is salaciously suggested there is something unseemly in their relationship. The gossip ends up costing Sarasa her job, while the notoriety of her past as a kidnapping victim had also been used against her by Ryo not to mention the casually biting remarks of some of her workplace friends. As she says though more of her hopes for her relationship with Ryo, people only see what they want to see and are often unable to look past their biases and preconceived notions.

As it turns out, Sarasa did have other people around her who cared for and supported her such as the sympathetic boss who tried to protect her both from her increasingly paranoid boyfriend and the judgemental guys from HR. She’d forgotten what Fumi had told her in that she was the only person who could own herself and she shouldn’t allow other people to bend her to her will, restoring to her the confidence and independence which had been taken from her by toxic familial history. Sarasa in a sense returns the favour, Fumi also burdened by a sense of rejection likening himself to a weak sapling his mother ripped from the soil before it had a chance to mature, as reflected in the poignant scene of Fumi fast asleep mirroring that of herself when she first arrived at the cafe. Poetically lensed by Hong Kyung-pyo, Lee lends the melancholy tale a poetic quality as the heroes eventually find a home in each other if only to be condemned to a perpetual wandering.

International trailer (English subtitles)