One of the more surprising things about Polar Rescue (搜救, sōujiù, AKA Come Back Home), a rare vehicle for Donnie Yen outside of the martial arts and action genres, is just how unheroic its panicked hero is. Though he may start off as a frantic parent who has our sympathies, we later begin to realise that he is at least severely flawed while there are also a few perhaps subversive hints towards the pressures of the modern China which have frustrated his attempts to be what he would assume a good father to be.

Despite later hints that the family is in a spot of financial bother, they’ve all gone on what looks like a fairly expensive skiing holiday in a European-style resort. The problem begins towards the end of their stay when eight-year-old Lele starts acting up in part because his father, De (Donnie Yen), promised to take him to Lake Tian to see the monster but has broken his word because of road closures due to the adverse weather. Wanting to make it up to his son, De decides to try going anyway via the backroads which are still open but soon enough gets stuck in a ditch. Events from this point on are deliberately obscured, but somehow Lele gets separated from his parents and sister and goes missing in the freezing wilderness.

Rather than a father’s one man race against time to find his missing son, the film soon shifts into familiar China has your back territory as the full force of artic rescue complete with helicopters and specialist equipment is deployed to find this one missing boy. De is still not satisfied and at several points frustrates the rescue effort by getting into trouble himself without really reflecting that it’s his own irresponsibility and paternal failure that have caused the rescuers to risk their own lives trying to find his son.

Though we might originally have sympathised with him, particularly as it seems clear Lele is behaving very badly and will not listen to either of his parents, we later come to doubt De on learning that Lele’s disappearance is at least in part related to an incredibly ill-advised though perhaps understandable parenting decision. As the film would have it, De is both too old fashioned in his authoritarian approach in which he’s often been violent towards his son, and too slack as evidenced by the boy’s bad behaviour. He’s failing in most metrics as a father given that he’s run into career difficulty as an engineer after challenging some of the nation’s famously lax safety regulations on a site he was working on he believed to be unsafe and then getting swindled on another construction project by a client who ran off with all the money. He also seems reluctant to allow his wife (Han Xue) to work to ease the family’s financial burden out of a mistaken sense of male pride.

This ties in somewhat to the propagandist themes as we see him totting up how much it would cost to send his kids to school overseas only for his wife to tut that Chinese education is good too, while the fact the family have two children also hints at a new ideal in the wake of the loosening of the One Child Policy to encourage correction to the rapidly ageing population. The rescuers, meanwhile, are portrayed in a perhaps slightly ambiguous light given than many of them quickly become sick of De and think they should stop looking given the unlikeliness of a child surviving alone for several days in such freezing conditions. Some even suspect De may be responsible for his son’s disappearance and is using them to cover up the crime. Even so, they get to sing a rousing song to the tune of Bella Ciao and re-echo their commitment not to give up until they’ve found Lele even if it turns out to be too late to save him.

A subplot about the two-sided nature of social media in cases like these is dealt with only superficially, while many other things do not quite make sense including the inclusion of a bear and his cub whose appearance, though obviously serving a symbolic purpose, seems like overkill. Nevertheless, there’s a good degree of ambiguity in the central disappearance that helps to head off the otherwise predictable nature of its trajectory.

Polar Rescue is out now in the US on Digital and Blu-ray courtesy of Well Go Usa.

US trailer (English subtitles)

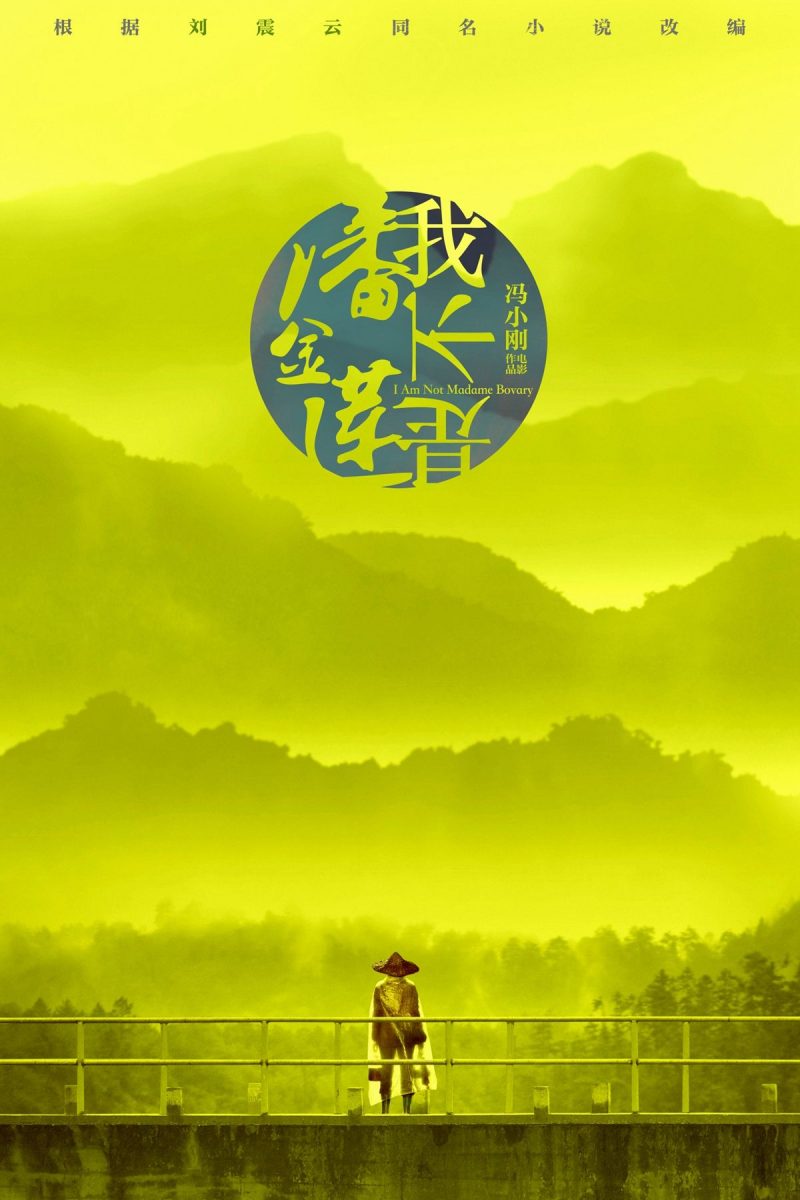

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and