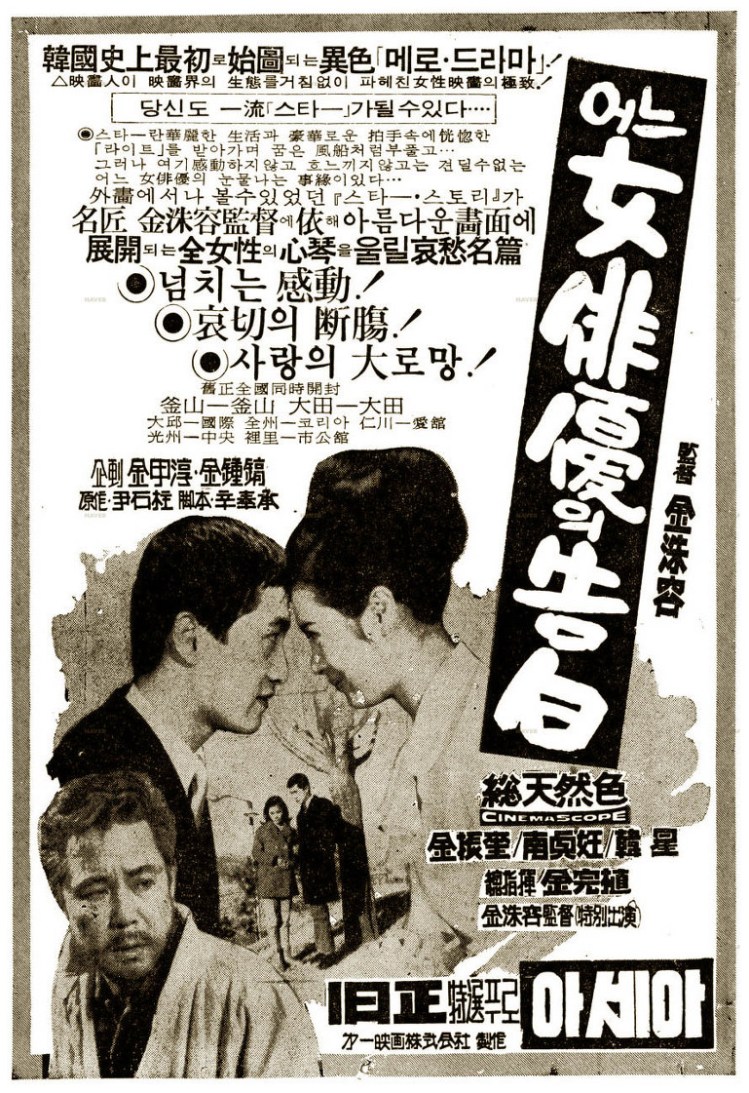

Korean filmmaking of the 1960s is sometimes referred to as a “golden age”, but the reality is that films were often churned out at a rapid pace for immediate distribution. Producers got an advance from local distributors, picked a scenario, assigned a suitable director and slotted in big name stars they already had under contract. For this reason production values are often low, but performance standard high despite the fact that many stars are bouncing around from one film to another shooting a scene here and a scene there. Director Kim Soo-yong filmed 10 features in 1967 – including his masterpiece Mist. Confessions of an Actress (어느 여배우의 고백 / 어느女俳優의告白, Eoneu Yeobaeu-ui Gobaek), inspired by a novel by Yun Seok-ju, is the kind of straightforward melodrama that was going out of style – a virtual remake of Chaplin’s Limelight with a little Phantom of the Opera thrown in, but Kim neatly repurposes it as a meta take on the Korean film industry of the day.

Korean filmmaking of the 1960s is sometimes referred to as a “golden age”, but the reality is that films were often churned out at a rapid pace for immediate distribution. Producers got an advance from local distributors, picked a scenario, assigned a suitable director and slotted in big name stars they already had under contract. For this reason production values are often low, but performance standard high despite the fact that many stars are bouncing around from one film to another shooting a scene here and a scene there. Director Kim Soo-yong filmed 10 features in 1967 – including his masterpiece Mist. Confessions of an Actress (어느 여배우의 고백 / 어느女俳優의告白, Eoneu Yeobaeu-ui Gobaek), inspired by a novel by Yun Seok-ju, is the kind of straightforward melodrama that was going out of style – a virtual remake of Chaplin’s Limelight with a little Phantom of the Opera thrown in, but Kim neatly repurposes it as a meta take on the Korean film industry of the day.

Kim Jin-kyu (played by the actor of the same name) was once a famous movie star, but heartbreaking tragedy ruined his career and now he’s a washed up drunk dreaming of the past. Hearing the dreaded “hey mister, didn’t you used to be somebody?”, Jin-kyu wanders into a film shoot and is thrown back to a happier time when he starred in prestige pictures with his regular co-star who was also his lover. Sadly, Miyong died of an illness leaving their last picture unfinished. The studio producers wanted to replace her and complete the movie, but Jin-kyu wouldn’t have it. They sued him for obstruction and his career was ruined. Jin-kyu was told that the child Miyong was carrying had died, but unbeknownst to him, a daughter was born and Miyong asked her friend Hwang Jung-seun to give the baby up for adoption and save it from the stigma of being illegitimate. Running into Jung-Seung at the shoot, Jin-kyu finds out his daughter is alive and determines to turn her into a great star – the only thing he can do for her as her father now that he is in such a sorry state.

Almost all of the characters in the film are named for their actors, though they are obviously not playing themselves in any biographical sense. Nevertheless, there is an intentional reflexivity in Kim’s decision to shift away from his literary source to towards one more immediately cinematic. Much as in Chaplin’s Limelight which does seem to provide a blueprint for the narrative, the arc is one of tragedy and redemption as Jin-kyu attempts to make up for lost time by imparting all his professional knowledge to the daughter he never knew and ensuring her success even at the cost of his own. Ashamed to introduce himself to her as a father given that long years of lonely drinking have reduced him to a broken old man, Jin-kyu gives his advice via letter and avoids seeing Jeong-im, longing to embrace her but afraid he’ll bring shame on her growing fortunes.

When Jin-kyu gets Jeong-im into show business, Kim gets a chance to put the Korean film industry on screen. He starts with a mildly sleazy producer and the established star who’s getting too old for ingenue roles but is desperate to hang on to her leading lady status. Nevertheless, she does have the option, as she points out, of a dignified escape through marriage should her career fail – something that is not an option for her male co-stars. As a young hopeful with no experience and nothing to recommend her beyond a pretty face, Jeong-im’s entry into the world of film is a baptism of fire. Rushed through makeup with its uncomfortable fake eyelashes and into an unfamiliar costume, Jeong-im’s rabbit in the headlights performance does not endear her to the director or more particularly the producer who is looking on from the wings in exasperation quietly calculating how much all of these extra takes are costing in wasted film. Nevertheless, the film is a success and, thanks to Jin-kyu’s careful tutoring, Jeong-im is on track for stardom.

Kim fetishises the camera, the process of filming with its bright artificial lights, tricks and techniques from the ice cold studio shoots to the difficult trips out on location. He makes full use of the relatively rare colour format utilising frequent superimpositions and montages, overlaying the bright neon lights of Seoul with the interior journey of our leading lady as she begins to find her voice. Making a final self cameo, Kim gives in to the inherently melodramatic quality of the underlying narrative but he does so somewhat ironically, rolling his eyes at the need for overly dramatic emotionality while actively embracing it, and lamenting the hardships of filmmaking while churning out his third picture in as many months. Confession of an Actress is not the salacious exposé promised by the title, but it is an illicit look at the decidedly unglamorous side of film production a world away from the bright lights and glossy magazines.

Available on DVD as part of the Korean Film Archive’s Kim Soo-yong box set. Not currently available to stream online.

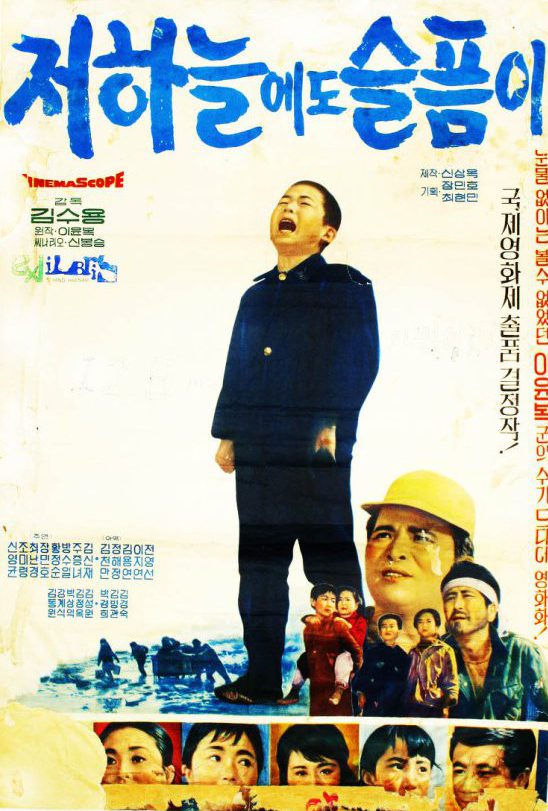

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?