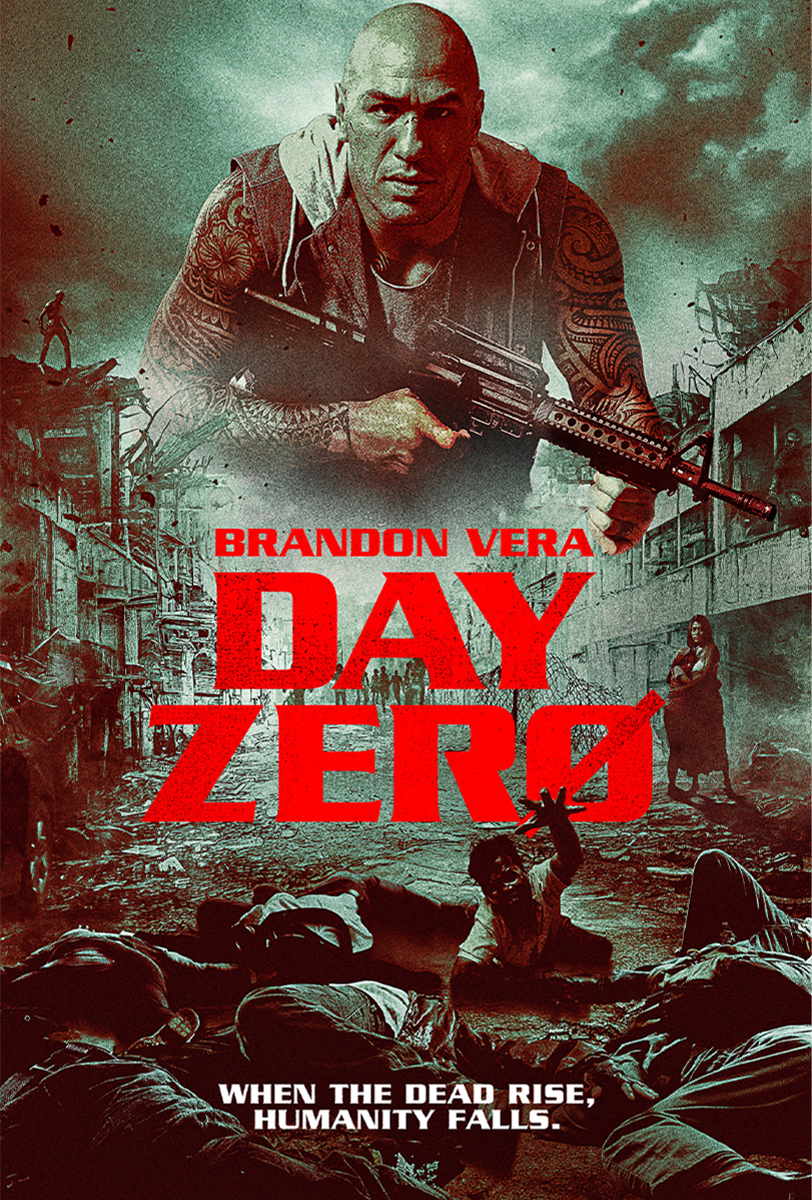

“This has been a really catastrophic day” according to a sympathetic, if not very reassuring, voice on the radio at the conclusion of Joey De Guzman’s zombie horror Day Zero. As the title suggests, the film takes place over 24 hours and marks the beginning but not end of the outbreak which will continue long after the end credits roll with ordinary people desperately trying to escape the seemingly endless stream of undead assailants.

Perfectly placed to face off against them is Emon (Brandon Vera), though he’s spent the last few years in prison for serious assault resulting in permanent disability. Emon is a former US special forces soldier and has apparently been a model prisoner so has won his parole and is hoping to return home to his wife Sheryl (Mary Jean Lastimosa), and daughter Jane (Freya Fury Montierro), who is deaf, but his hopes are dashed when he’s surrounded by other prisoners who attack him when he sticks up for his timid friend Timoy (Pepe Herrera) at which point his release is cancelled. As it turns out, that doesn’t matter very much because of an outbreak of suspected Dengue fever which has mutated causing corpses to come back to life and attack people. The warden apparently had a moment of compassion before becoming a zombie and opened the gates telling the prisoners to escape and allowing Emon and Timoy to try to make their way back to Sheryl and Jane.

Like the similarly themed Train to Busan, the narrative arc is paternal redemption as Emon must reclaim his role as a father by becoming a man who can protect his family even if it’s true that it’s the same self-destructive forces, his capacity for violence, which enable him to do so. Even the warden had remarked on Emon’s intimidating physicality admitting that it’s unsurprising the other inmates largely leave him alone while his attempt to impress Sheryl by telling her how some guys hassling Timoy had walked away when they saw him coming backfires as she sees it as evidence that he really hasn’t changed and is still wedded to a destructive code of masculinity founded on dominance and violence. The implications of the fact he learned these skills as a member of the US military otherwise goes largely uncritiqued as does the presence of heavy weaponry including an assault rifle in the home of a local police officer.

Then again, police chief Oscar (Joey Marquez) later becomes a secondary enemy after turning on some of the other survivors when someone close to him is zombified though it’s Sheryl, not Emon, who must eventually contend with him. The two men present conflicting visions of fatherhood, one protective and the vengeful prepared to kill a child just to get revenge against her father. In any case, Emon must learn to channel his violence in a more positive direction by killing as many of the zombified locals as possible to clear a path for Sheryl and Jane to escape the apartment building where the family have become trapped. Though he may eventually be able to reclaim his paternity, it’s also true the problematic violence that allows him to do so may prevent him from reintegrating into his family in a more “normal” post-outbreak world.

The film doesn’t have much time to go into its zombie mythology save the allusion to Dengue fever, but does give them the novel quality of falling asleep when not otherwise engaged allowing the survivors to escape through a life or death game of grandmother’s footsteps. This leaves Jane additionally vulnerable because of her disability but also grants her an advantage as the family can communicate through sign language to avoid waking the zombies. Most of the action is however left to Emon who staggers through darkened corridors armed with an assault rifle, pistol, knife, and finally just his fists facing off against the zombie hoards hoping to hold back the tide so his family can escape to look for safety and stability. Mostly serious in tone, the film allows a few moments of dark comedy such as a teenage survivor’s attempt to take care of a zombie using a rechargeable drill frustrated by its battery life, but mostly relies on the claustrophobic atmosphere of the darkened apartment block and heartwarming story of familial reconciliation along with intense zombie action to carry itself through.

Day Zero is available on Digital now in the US and released on DVD & blu-ray July 11 courtesy of Well Go USA.