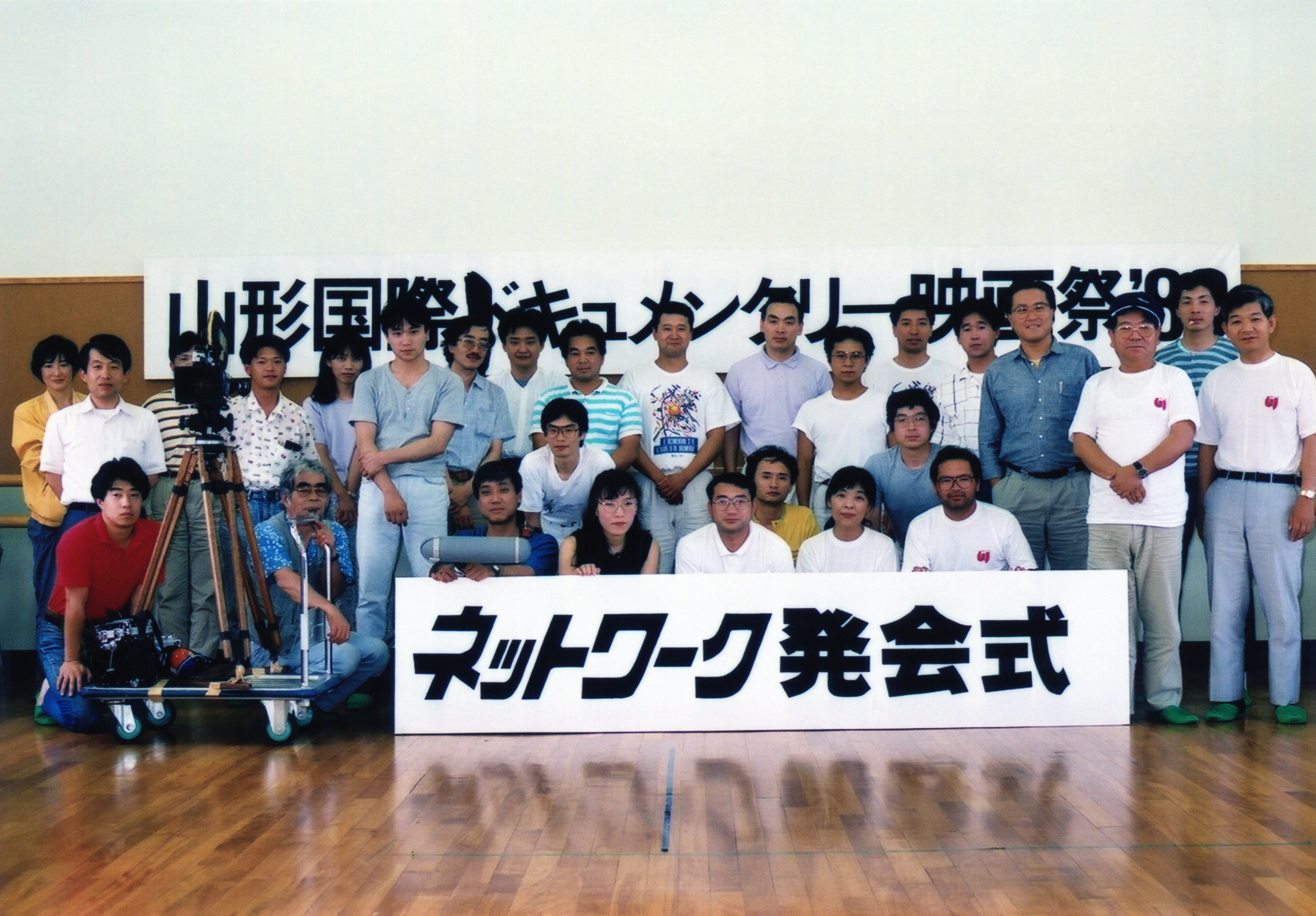

As the opening of Toshio Iizuka’s A Movie Capital (映画の都, Tokyo no Miyako) makes plain, 1989 was a year of turbulence all over the world but also perhaps also of hope as many of the directors invited to the very first Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival often insist in positioning their art as an act of resistance against authoritarianism. In essence a visual record commemorating the festival’s inauguration, Iizuka’s film also has its meta qualities interrogating not only what documentary is and what it’s for but its potential as a means of bringing disparate communities together in an exchange of truth and solidarity.

In fact, the film opens with a brief prologue dedicated to Dutch documentarian Joris Ivens, who sadly passed away just before the festival opened, contrasting Ivens’ 1928 work The Bridge with the box office hit of that year in Japan, Shozo Makino’s Chushingura. Jumping into the film proper we witness something similar as the tranquility of the Bubble-era nation is directly contrasted with the events of Tiananmen Square as seen in a video sent to the festival by a Chinese associate living in Hong Kong. In actuality, the first Yamagata featured no films from Asia in its competition section provoking a symposium in which a number of Asian directors, producers, and critics discuss why that might be. Ironically enough, fifth generation Mainland Chinese director Tian Zhuangzhuang (The Horse Thief) was invited but unable to speak because, as his wife explains during an exasperating phone call, it’s not as easy for someone from China to travel abroad as it would be for someone elsewhere. The authorities haven’t granted him permission to leave and so he cannot even apply for a passport.

Censorship and an element of personal danger to oneself or one’s family are otherwise cited as reasons documentary filmmaking has not taken taken off in Asia. The director of May 80 Dreamy Land which concerns the Gwangju Uprising is also unable to attend because he is currently on trial. Meanwhile, his representative Kong Su-Chang laments that he is among the older members of his small circle of documentary filmmakers who are of a generation without mentors having to teach themselves how to make films because there was no one there teach them. Filipino directors meanwhile cite the continuing influence of America along with wealth inequality as potential reasons the documentary has not flourished while asking if documentary and entertainment are in some way incompatible given that documentary is at its most popular at moments of crisis.

Still as almost every interview states at one time or another, their primary goal is to make sure the voices of their subjects are heard and their faces seen determined to capture the everyday experiences of ordinary people as honestly as possible. While it’s obviously true that none of them were themselves included in the competition, many directors also claim that more important is the opportunity to meet other filmmakers in order to generate friendships and exchange ideas. They see their mission as making the world a better place to live hoping to challenge the status quo through their filmmaking while what Yamagata becomes to them is an opportunity to improve the fortunes of documentary filmmakers throughout Asia through mutual solidarity while the town of Yamagata itself also comes together as a community in order to celebrate documentary art even recruiting the marching band of a local primary school to help.

One director’s suggestion that the future will become harder for dictators thanks to the democratisation of technology may in a sense be naive but in its own way true in the ability of ordinary people to record their own stories even if they face the same difficulties and dangers. Even so Iizuka’s assembled footage from the films which played that first edition alongside interview and Q&A footage not only help to give an impression of the open and enquiring nature of the festival, but also to interrogate itself and its art asking what it’s for and what purpose it can serve at a moment of geopolitical instability as the Berlin Wall falls and the echoes of Tiananmen reverberate while documenting not only a single event but its purpose and intention.

A Movie Capital streams worldwide (excl. Japan) via DAFilms Jan. 17 to Feb. 6 as part of Made in Japan, Yamagata 1989 – 2021 (films stream free Jan. 17 – 24)