Kyokutei Bakin thinks he’s a hack who writes inconsequential pulp that will be forgotten faster than yesterday’s headlines. He’d never believe that people hundreds of years later would still be talking about his work. Yet he may have a point in his conviction that people crave simple stories where good triumphs over evil specifically because the real world is not really like that and a lot of the time the bad guys end up winning. But does that mean then that all his stories are “lies” and he’s irresponsible for depicting the world not the way that it is but the way he wants it to be?

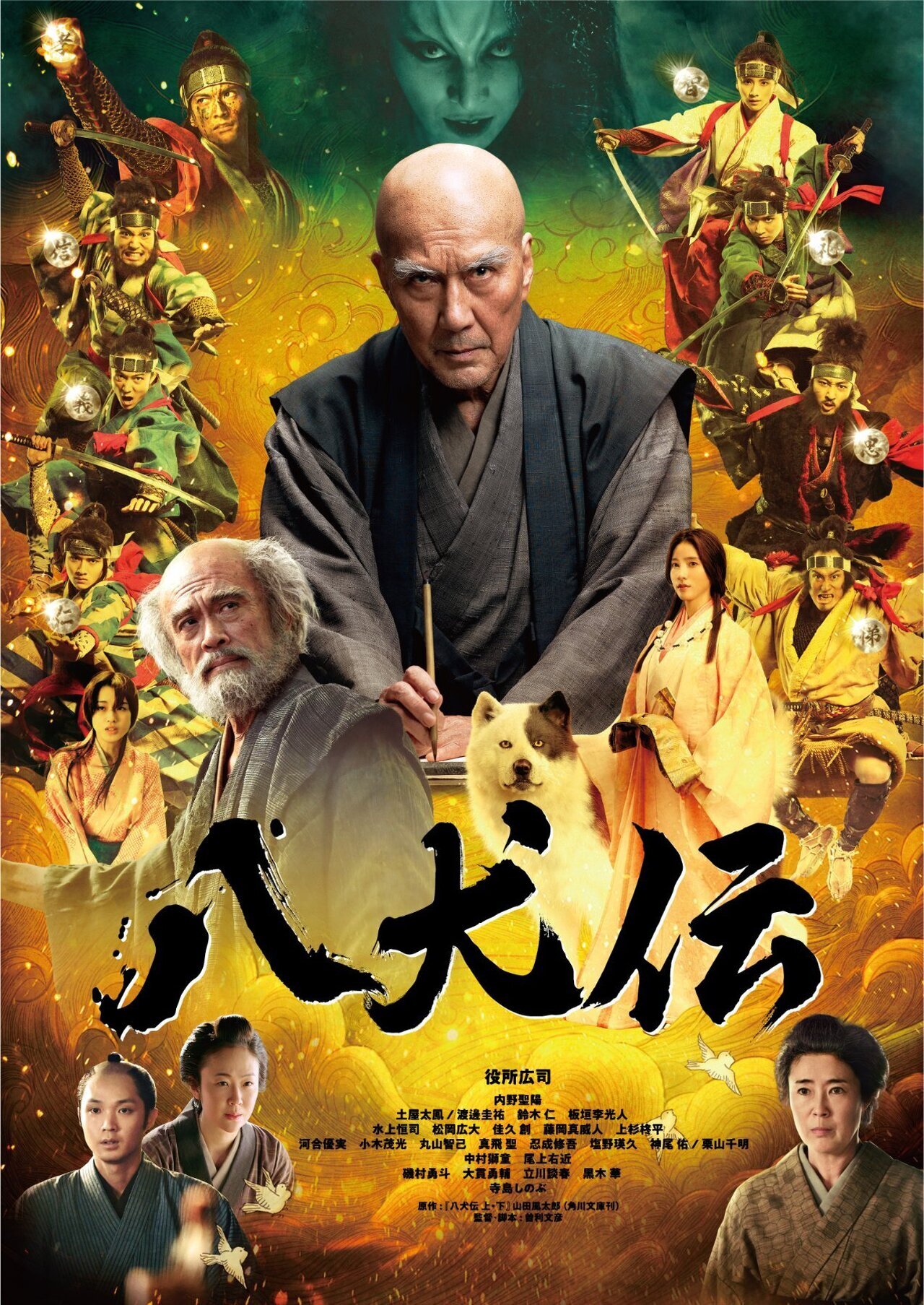

Fumihiko Sori’s Hakkenden (八犬伝) is on one level an adaptation of the famous tale probably most familiar to international audiences as The Legend of the Eight Samurai, and also a story of its writing and the private doubts and fears of its author. In dramatising the tale, Sori plays fantasy to the max and revels in Bakin’s outlandishness. An unusually picky Hokusai (Seiyo Uchino), Bakin’s best and he claims only friend and unwilling collaborator, points out that his use of guns is anachronistic because they didn’t come to Japan until 60 or 70 years after the story takes place but Bakin doesn’t care. He says people don’t notice things like that and all they really care about is that good triumphs in the end, so he’ll throw in whatever he feels like to make a better story. In any case, the tale revolves around magical orbs, evil witches, dog gods and good fairies, so if you’re worrying about there being guns before there should be, this isn’t the story for you.

Hokusai is also shocked that Bakin has never been to the place where the story is set, but as he tells him it all happened long ago and far away so going there now would be pointless. Even so, Hokusai needs to see what he draws which is why he spends half his life on the road costing him relationships with his family. Whatever else anyone might say about him, and he admits himself to being a “difficult” person, Bakin is very close to his family even if his wife yells at him all the time for being rude to influential people and not making any money when he could have just taken over her family’s clog-making business rather than carry on with this writing malarkey. His biggest ambition is that his son become a doctor to a feudal lord and thereby restore their samurai status which on one level points to a kind of conservatism that doesn’t matter to Hokusai and singles Bakin out as a tragic figure because the age of the samurai is nearing its end anyway.

In his fantasy, however, he hints at and undoes, up to a point, injustices inflicted on women in the romance between Shino (Keisuke Watanabe) and Hamaji (Yuumi Kawai) who is almost forced into a marriage with a wealthy man because of her adoptive parents’ greed but is finally revealed to be a displaced princess and returned to her father who is thereby redeemed for having accidentally killing his other daughter in a mistaken attempt to control her after accidentally promising her in marriage to a dog god without really thinking about what he was saying. A neat parallel is drawn in a brief mention of Hokusai’s artist daughter Oi and Bakin’s daughter-in-law Omichi (Haru Kuroki) who did not receive an education and is almost illiterate but finally helps him to complete the story by transcribing it in Chinese characters he teaches her as they go after he loses his sight.

As his literary success increases, Bakin’s own fortunes both improve and decline. He becomes wealthier and moves to nicer houses in samurai neighbourhoods, but his son Shizugoro’s (Hayato Isomura) health declines and he never opens his own clinic like he planned while remaining committed to the idea that his father is actually a great, unappreciated artist. In a way, completing the story gives Bakin a way to say the world could be kind and just even if it has not always been so to him. He needs to maintain the belief in a better world in order to go living even if he feels it to be inauthentic while his life itself is a kind of fiction. On a trip to the theatre, he ends up seeing Yotsuya Kaidan and is at once hugely impressed and incredibly angry. The world that Nanboku sees is the opposite of his own. People are selfish and greedy. The bad are rewarded and the innocent are punished. Yet perhaps this is the “reality” of the way the world really is, where as his work is a wishful fantasy. All he’s doing is running away from the truth. But then, as his son’s friend tells him, if a man devotes himself to the ideal of justice and believes in it all his life, then it becomes a reality and ceases to be fiction. There is something quite poignant about the dog soldiers coming to take Bakin to the better world he dreamed of where bad things happen but good always triumphs in the end, which has now indeed become a reality if only for him.

Hakkenden screens 13th June as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)