Director Kim Soo-yong began his career while still in the military shortly after the end of the Korean War, originally making “military films” for the Ministry of Defence’s Film Department. Since his debut in 1958, Kim had directed 19 features before the release of his “breakout” transition into mainstream cinema with Bloodline (血脈 / 혈맥, Hyeolmaek, AKA Kinship) – an early example of the “literary film” with which Kim would become heavily associated. Like much of Kim’s later work, Bloodline is a socially progressive, empathetic look at the lives of everyday people living in very difficult circumstances but trying their best to be their best all the same.

Director Kim Soo-yong began his career while still in the military shortly after the end of the Korean War, originally making “military films” for the Ministry of Defence’s Film Department. Since his debut in 1958, Kim had directed 19 features before the release of his “breakout” transition into mainstream cinema with Bloodline (血脈 / 혈맥, Hyeolmaek, AKA Kinship) – an early example of the “literary film” with which Kim would become heavily associated. Like much of Kim’s later work, Bloodline is a socially progressive, empathetic look at the lives of everyday people living in very difficult circumstances but trying their best to be their best all the same.

The film opens in 1946, immediately after the end of the Second World War which is also, of course, the end of the Japanese Colonial Period and the beginning of a short-lived Korean post-war democracy. A small shantytown courtyard in Seoul is home to three families – the wealthier Kim Deok-sam (Kim Seung-ho) who was once a successful mining agent in Japan and lives with his grown-up son Geobugi (Shin Seong-il), the tinker “Ggangtong” (Choi Nam-hyun) who lives with his second wife Ongmae (Hwang Jung-seun) and daughter Boksun (Um Aing-ran), and Wonpal (Shin Young-kyun) whose wife (Lee Kyoung-hee) is seriously ill while his daughter (Lee Gyeong-rim) is disabled. Wonpal, a refugee from North Korea, is also responsible for his elderly Christian mother (Song Mi-nam) and younger brother Wonchil (Choi Moo-ryong) who went to university in Japan but has come back with literary aspirations and has so far refused to get a job and help support the family.

The world of 1946 is an immensely chaotic one in which the old order has been destroyed but nothing has yet arrived to take its place. For good or ill, the American occupation has become an essential economic force – Deok-sam is forever urging Geobugi to get a job on the American military base which he believes will pay well both in terms of salary and a series of perks official or otherwise. Meanwhile, Wonchil’s old girlfriend, Oki (Kim Ji-mee), is one of many women who’ve found themselves without support in the desperate post-war economy and has become the mistress of an American serviceman. Like Won-chil she came from the North with nothing and was left with no other option than entering the sex trade as a bar girl – the same fate which awaits Boksun at the behest of her step-mother who plans to sell her to a bar to provide for the family and has been forcing her to learn bawdy folksongs in order to become a fully fledged “gisaeng”.

Both generations are, to a particular way of thinking, intensely selfish. The old, still bound up with a series of ancient social codes, try to oppress their children in the same way they were oppressed only now they’re in charge and reluctant to cede the little power they have now they finally have it. The parents want their children to do what is best for the “family” regardless of their personal happiness. Deok-sam is determined that his son should get a job with the Americans, Ongmae is determined that Boksun become a bar girl so that she and her husband can live in comfort, while Wonpal just wants to support his wife and daughter but can’t and resents his brother for not helping more. Yet the young people want their freedom and to be a part of the world which is opening up before them. They are filial and want to look after their parents, but reject their oppressive demands especially when it comes to their romantic futures. Ggangtong disagrees with his wife’s decision to sell Boksun and has hatched a plan to marry her off to a nice barber who has asked for her hand and seems to have good prospects, but Boksun is in love with Geobugi and wants to marry him, only he is dragging his feet because he has no money and worries about his father. Geobugi wants to get a job in a nearby factory, but hasn’t had the courage to go against his father’s wishes.

Kim Soo-yong, as unjudgemental as always, places his sympathies firmly with the young as they demand their right to choose while also reserving a right to a fresh start for all – including bar girl Oki who is allowed to simply walk away from her life in the sex trade and into a happier future once the moody Wonchil has learned to accept her past and also reconciled with his brother, literally “repairing” the family home in fixing the hole in the leaky roof through which Wonpal’s wife once used to watch the stars. Meanwhile, Boksun and Geobugi also look forward to their brighter future with jobs in a progressive factory which is friendly, bright, and open. Ggangtong, who resented his wife’s feudal desire to sell their daughter but also tried to arrange her marriage, is the first to see that his era has ended, affirming that the youngsters were right to leave and that the world now belongs to them. Eventually sense is seen, the old give way and accept the desires of the young, realising that they will lose their children if they cannot learn to set them free. The world has changed, mostly for the better, and familial bonds will have to change with it but they will not necessarily have to break if each side is willing to give ground in expectation of a better tomorrow.

Bloodline is available on English subtitled DVD courtesy of the Korean Film Archive in a set which also includes a bilingual booklet featuring an essay by director Kim Soo-yong, and an article about the restoration by the Korean Film Archive’s Kim Ki-ho, as well as full cast and crew credits.

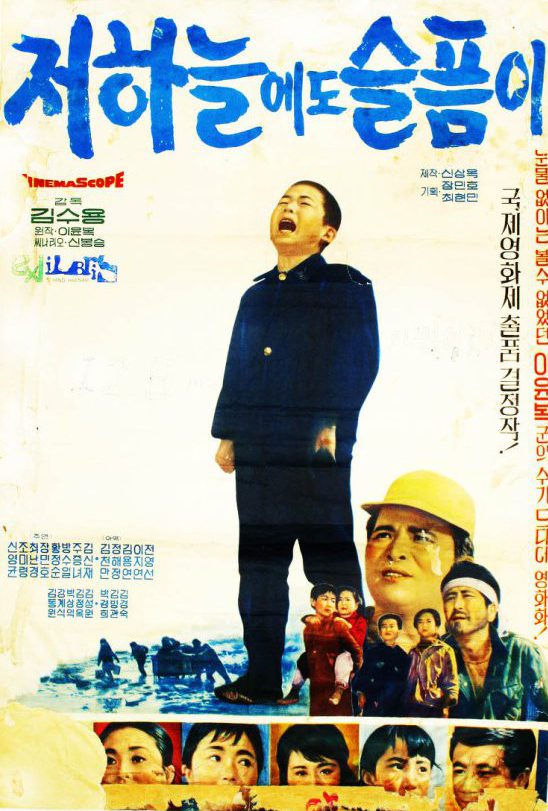

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?