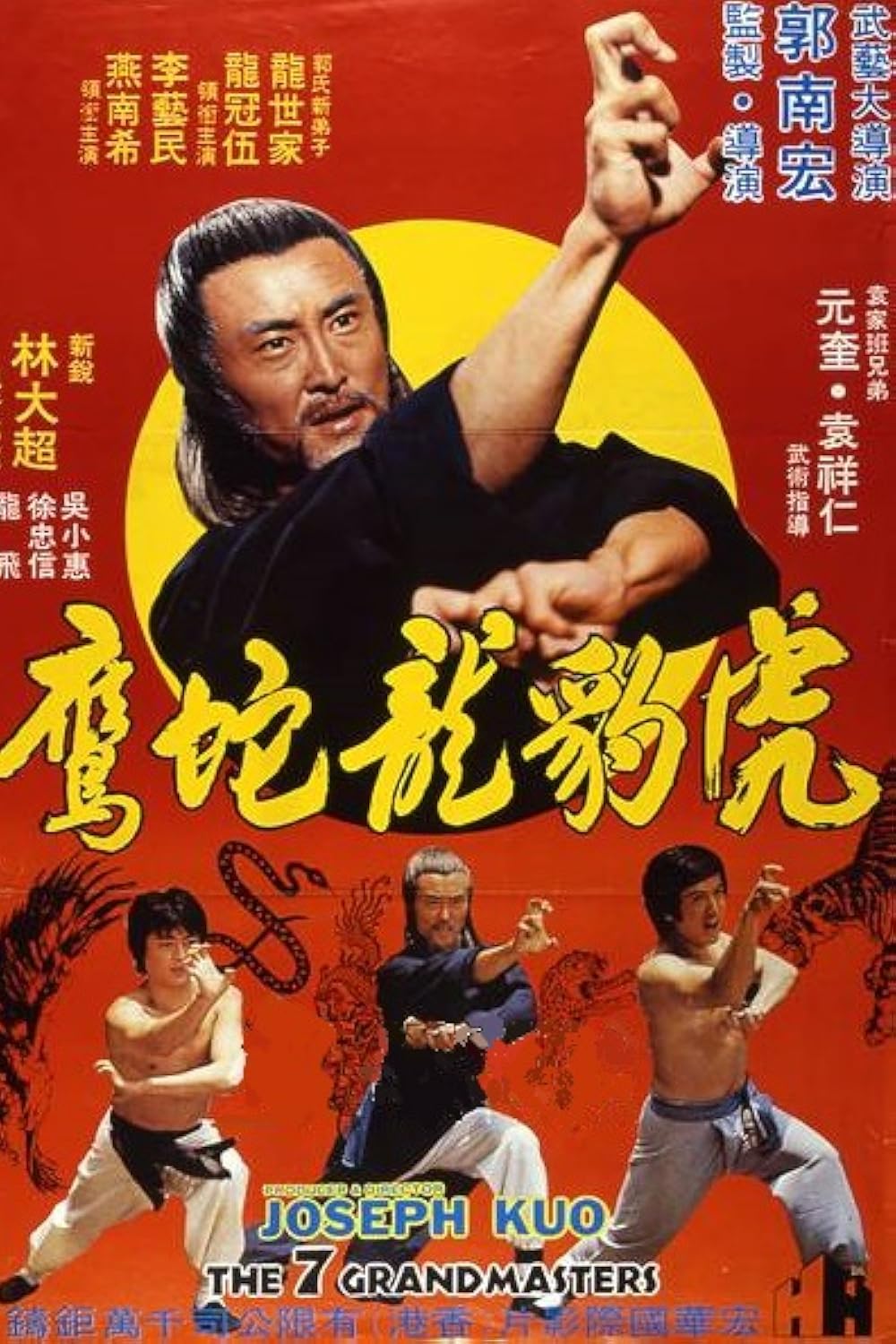

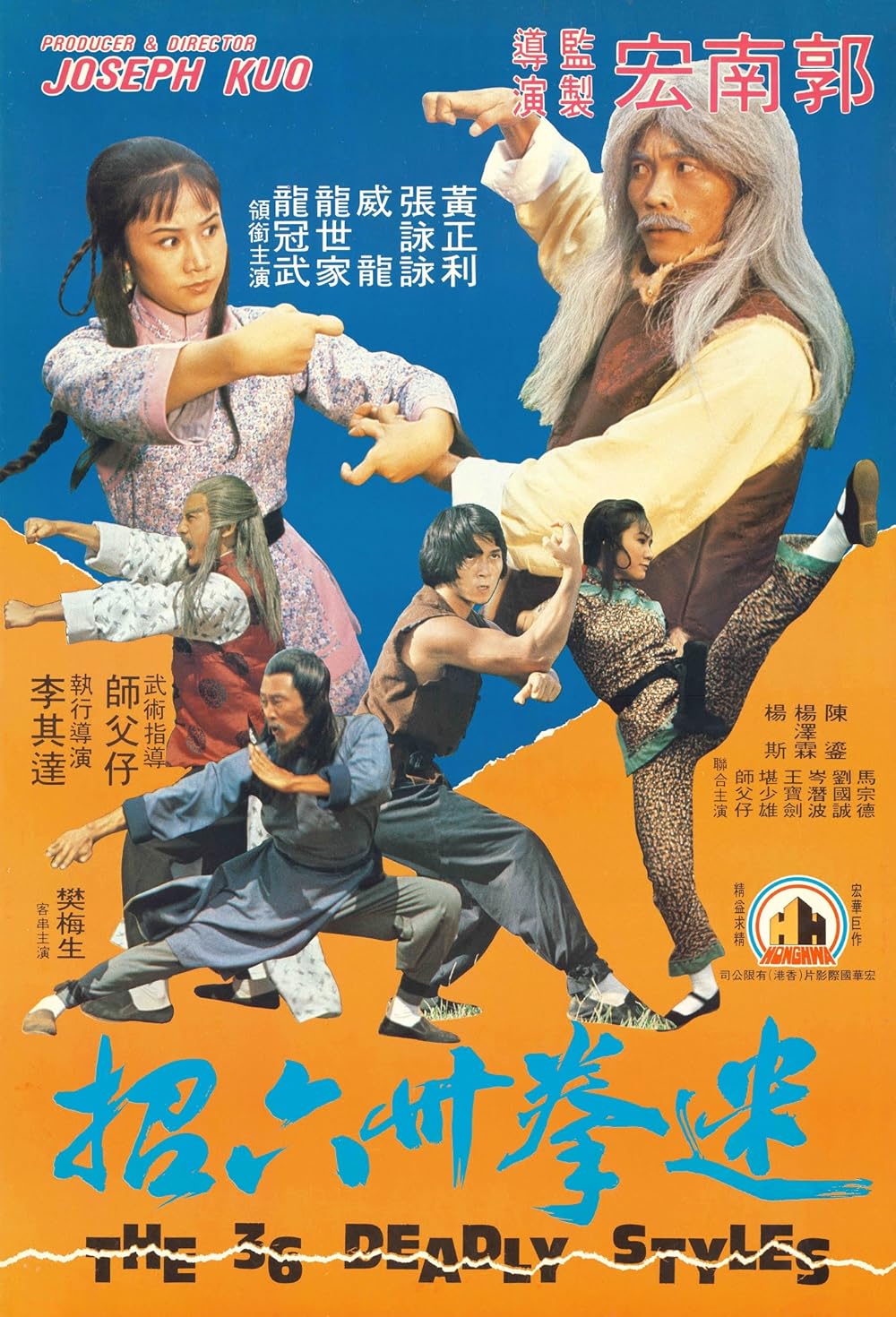

First you and your uncle are forced to flee for your life after getting attacked in a forest, then your uncle dies, you wake up in a monastery where you’re not a monk but the head monk keeps making you do all the chores anyway, and you still have no real idea of what is going on. That’s what happens to poor Wah-jee (Nick Cheung Lik) in Joseph Kuo’s wilfully confusing kung fu drama The 36 Deadly Styles (迷拳三十六招) which leaves us as much in the dark as the hero as he finds himself inexplicably pursued by a man with a red nose and his brothers who are each for some unexplained reason wearing ridiculous wigs.

As much as we can gather, Wah-jee is on the run because the brother of a man his late father apparently killed by accident after messing up a kung fu move seeks vengeance against his entire family, leaving his uncles scattered and apparently unknown to him. As a young man, however, he is less than impressed with life in the monastery and often displays a comically cocky attitude, though if his torment of two of the lesser monks is intended to be comedic, it often comes off as cruel and bullying rather than just silly banter. Meanwhile, he remains clueless as to how to complete basic tasks familiar to the monks and even manages to get himself into a fight when sent to buy soy milk after forgetting he’d need to pay for it..

While all of this is going on, Kuo switches back and forth between a secondary plot strand concerning another man searching for the book of the 36 Deadly Styles before tracking down the man who’s supposed to have it only to be told he burnt the book ages ago without even reading it because it caused too much trouble in the martial arts world. It’s unclear how or if these two plot strands are intended to be connected, but they do perhaps hint at the confusing nature of personal vendettas and ironically destructive quests for full mastery over a particular style. Tsui-jee’s father (Fan Mei-Sheng) effectively splits his knowledge between Wah-jee and his daughter as a complementary pair of offence/defence partners.

Meanwhile, Huang (Yeung Chak-Lam) and Tsui-jee’s father are also afflicted by pangs to the heart as a result of their previous battles, which can only be eased with strange medicine and herbal wine. Huang is a Buddhist monk but is seen early on skinning a live snake in order to make such a concoction. These are presumably symbolic of a bodily corruption caused by violence and the slow poisoning of the unresolved past. Wah-jee, a child at the time of his father’s transgression, is also forced to inherit this chaos of which he has little understanding and no real stake save vengeance for his familial disruption and a vindication for his father and brothers. If there is any kind of moral it seems to be in the ridiculous futility of vengeance as dictated by the codes of the martial arts world which demands that honour be satisfied even when it has lost all objective meaning.

In any case, the narrative is largely unimportant merely connecting (or not) the various action scenes each well choreographed and expertly performed. Wah-jee undergoes a series of training sequences both at the monastery and after uniting with his second uncle who has some idiosyncratic teaching practices of his own that require Wah-jee to humble himself in order to learn. Then again, there are enough strange details to leave us wondering what is exactly is really going on such as Tsu-men suddenly turning up dressed as a woman looking for someone other than Wah-jee, eventually used for another bit of awkward comic relief as he struggles to write a letter and has to use drawings to make his point because he can’t remember the right characters. None of this makes any sense, but perhaps it never does when you live for the fight alone.