An “evil learning sinner” and a young man fixated on Neo-Buddhist thought develop an unlikely friendship while compiling an encyclopaedia about sea life in Lee Joon-ik’s contemplative period drama, The Book of Fish (자산어보, Jasaneobo). Like those of Hur Jin-ho’s Forbidden Dream, the hero of Lee’s historical tale of competing ideologies dreams of a classless future but is exiled from mainstream society not for his revolutionary rejection of a Confucianist hierarchal society but for his embrace of Western learning and religion.

Like his two brothers, Chung Yak-jeon (Sol Kyung-gu) reluctantly joins the imperial court but later falls foul of intrigue when the progressive king falls only to be replaced by his underage son controlled by the more conservative dowager empress. Having converted to Christianity, Yak-jeon and his brothers are faced with execution but unexpectedly reprieved when the oldest agrees to renounce Catholicism and root out other secret Christians. Yak-jeon is then exiled to a remote island while his better known brother, the poet Yak-yong (Ryu Seung-ryong), is sent to the mountains. On his arrival, the local governor introduces Yak-jeon as a “traitor” and instructs the islanders not to be too friendly with him but island people do not have it in them to be unjustly unkind and so Yak-jeon is, if warily, welcomed into their community. “He maybe be a traitor, but he’s still a guest” his new landlady (Lee Jung-eun) explains as she prepares him some of the local seafood.

Yet Yak-jeon encounters resistance from an unexpected source, intellectual fisherman Chang-dae (Byun Yo-han) who goes to great lengths to acquire scholarly books despite his otherwise low level of education. Somewhat patronisingly, Yak-jeong offers to tutor him, but Chang-dae is a rigid thinker who believes the world is going to hell because people have forgotten their Confucian ideals so he’s no desire to be taught by a treacherous “evil learner” or be sucked in to his dangerous Catholicism. Surprisingly, however, for a man who risked death rather than renounce his religion, Yak-jeong is no fanatic and in fact does not appear to practice Christianity at any point while living on the island. What he professes is that Eastern and Western thought need not be enemies but can go hand in hand while a rigid adherence to any particular doctrine is what constitutes danger.

Chang-dae had insisted that he studied “to become a better human” but he also has a large class chip on his shoulder as the illegitimate son of a nobleman who refuses to acknowledge him, fully aware that as a “lowborn” man he is not allowed to take the civil service exam and in any case would not have the money to buy his way in to the court. Despite later professing egalitarianism, Yak-jeong treats the islanders, and particular Chang-dae, with a degree of superiority extremely irritated by Chang-dae’s refusal to become his pupil in the slight of his elite status often making reference to his “low birth”. Confessing his desire for a classless society with no emperor, however, Yak-jeong encounters unexpected resistance as the young man finds it impossible to envisage a world free of social hierarchy based on rights of birth and swings back towards desiring the approval of his elite father in the determination to climb the ladder rather than pull it down.

Chang-dae finds himself caught between two fathers who embody two differing ways of being, Yak-jeong advising him to think for himself rather than blindly follow Confucianist thought, while his father encourages him to towards the court and the infinite corruptions of the feudal order. Chang-dae does begin to interrogate some of the more persistently problematic elements of Confucian teaching including its views on women and entrenched social hierarchy but also feels insecure and desperately desires conventional success and entrance into a world he thinks unfairly denied to him. Once there, however, he discovers he cannot submit himself to duplicities of feudalism. The islanders are being taxed to into oblivion, not only is there a random counter-intuitive tax on pine trees but the government is also extracting taxes from the family members of the deceased as well as newborn babies while cutting sand into the rice rations it promises in return. His father and superiors laugh at him for his squeamishness, seeing nothing at all wrong in the right of the elite to exploit the poor. Trying to blow a whistle, Chang-dae is reminded that the courtly system is an extension of the monarchy, and so criticising a lord is the same as criticising the king which is to say an act of treason.

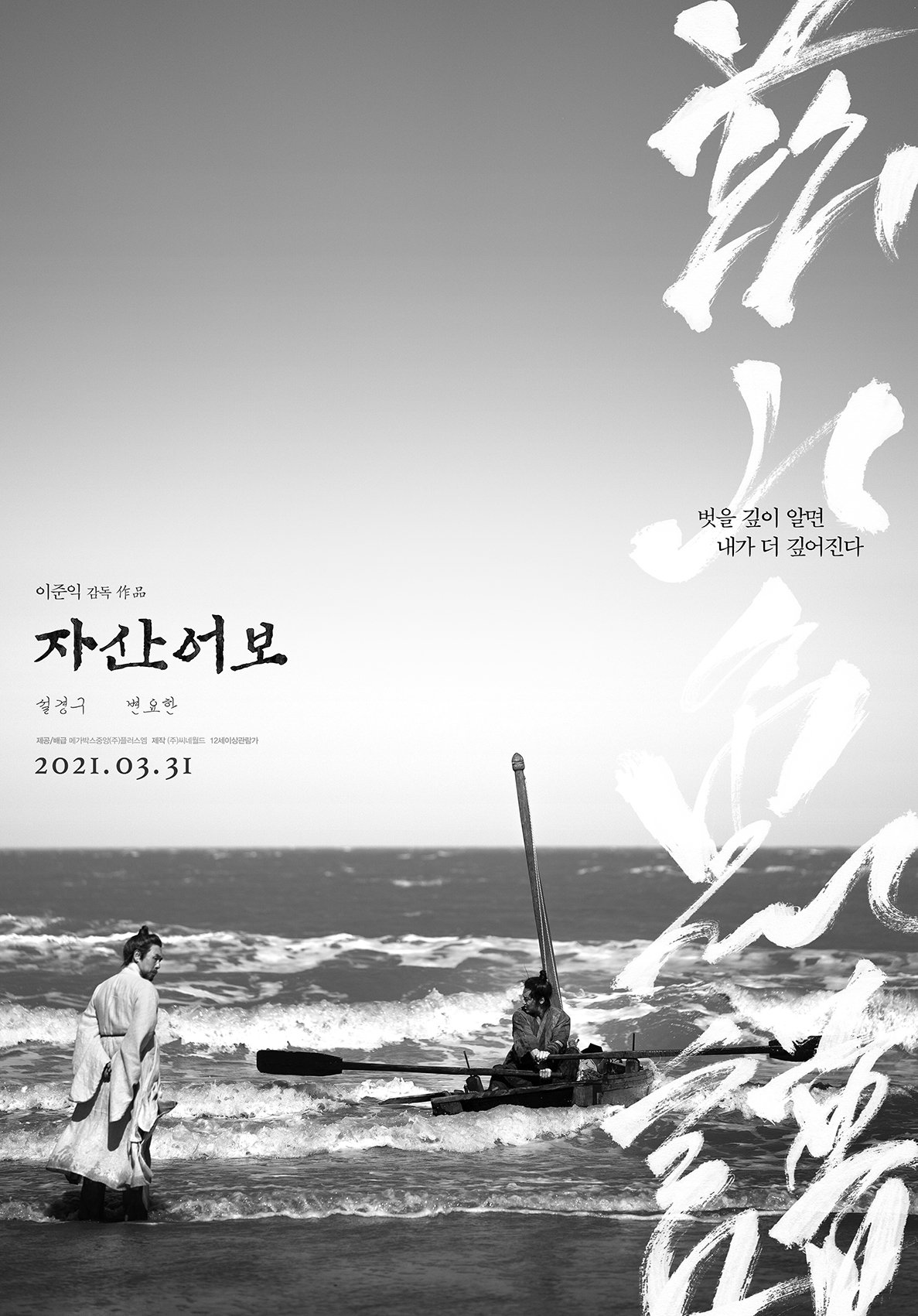

Having been accused of treason himself, Yak-jeong declines to enact his revolutionary ideas penning only a couple of books during his time in exile in contrast to his brother who published many treatises on effective government. Yak-jeong explains he dare not risk writing his real views which is why he’s immersed himself in the beauty of the natural world, exercising his curiosity writing about fish while making use of Chang-dae’s vast knowledge of the sea. The two men develop a loose paternal bond but are later separated by conflicting desires, Chang-dae eventually choosing conventional success over personal integrity only to regret his decision on being confronted with the duplicities of the feudal order. Shot in a crisp black and white save for two brief flashes of colour and inspired by traditional ink painting, Lee’s contemplative drama finds itself at a fracture point of enlightenment as two men debate the relative limits of knowledge along with the most effective way to resist a cruel and oppressive social order but eventually discover only wilful self exile as Chang-dae learns to re-embrace his roots as an islander along with the openminded simplicity of Yak-jeong’s doctrine of catholicity in learning.

The Book of Fish screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (Korean subtitles only)

“Hell Joseon” manifests as “toxic gas” in Lee Sang-geun’s Exit (엑시트). Millennial “slackers” losing out in Korea’s increasingly cutthroat economy find themselves consumed by their own sense of failure while those around them only compound the problem by branding them useless, no-good layabouts, writing off the current generation as lazy rather than acknowledging that the society they have created is often cruel and unforgiving. Yet, oftentimes those “useless” skills learned while having fun are more transferable than one might think and the ability to find innovative solutions to complex problems something not often found in the world of hierarchical corporate drudgery.

“Hell Joseon” manifests as “toxic gas” in Lee Sang-geun’s Exit (엑시트). Millennial “slackers” losing out in Korea’s increasingly cutthroat economy find themselves consumed by their own sense of failure while those around them only compound the problem by branding them useless, no-good layabouts, writing off the current generation as lazy rather than acknowledging that the society they have created is often cruel and unforgiving. Yet, oftentimes those “useless” skills learned while having fun are more transferable than one might think and the ability to find innovative solutions to complex problems something not often found in the world of hierarchical corporate drudgery.