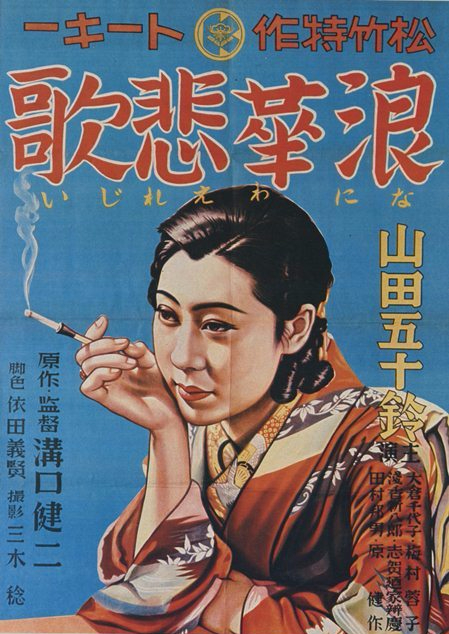

Kenji Mizoguchi felt he was hitting his artistic stride with Osaka Elegy (浪華悲歌, Naniwa Elegy). Released in 1936 amid the tide of rising militarism, Mizoguchi’s tale of sacrifice and betrayal is strikingly modern in its depiction of female agency and the impossibility of escape from the confines of familial power and social oppression. Sexual harassment was not so much a problem as an accepted part of life in 1936, but as always it’s never the men who suffer. In depicting life as he saw it, Mizoguchi’s vision is bleak, leaving his forward striding heroine adrift in a changing, volatile world.

Kenji Mizoguchi felt he was hitting his artistic stride with Osaka Elegy (浪華悲歌, Naniwa Elegy). Released in 1936 amid the tide of rising militarism, Mizoguchi’s tale of sacrifice and betrayal is strikingly modern in its depiction of female agency and the impossibility of escape from the confines of familial power and social oppression. Sexual harassment was not so much a problem as an accepted part of life in 1936, but as always it’s never the men who suffer. In depicting life as he saw it, Mizoguchi’s vision is bleak, leaving his forward striding heroine adrift in a changing, volatile world.

Beginning not with the protagonist, Mizoguchi first introduces the quasi-antagonist, lecherous boss Asai (Benkai Shiganoya), who feels trapped in an unhappy marriage to a bossy, shrewish woman. For Asai, the head of a family pharmaceuticals firm, work is an escape from family life and the same is also true for telephone switchboard operator Ayako (Isuzu Yamada) who lives with her feckless father whose gambling problem has left them all with serious debts. Asai, encouraged by Fujino (Eitaro Shindo), a colleague well known to be a womaniser, has developed a crush on the meek and innocent Ayako and continues to harass her at work, invading her personal space and pleading with her to have dinner with him. She declines and leaves distressed but when her father is discovered to have embezzled a large sum of money from his company which they will let go if he pays it back, Ayako is faced with a terrible dilemma.

In essence, Osaka Elegy is a hahamono which shifts focus to the self-sacrificing daughter of motherless family rather than a betrayed mother who gives all for her children and receives little in return. Ayako flits between resentment of her useless father’s poor parenting which has left her the sole figure of responsibility for a younger sister and older brother who already seem to hate her even before her present predicament. Yet however much she loathes her father for his weaknesses, she still feels a responsibility to help him and to avoid the social stigma should he fail to repay the money he stole and is arrested. Once she makes the difficult decision to become Asai’s mistress, her fate is sealed. She loses her future, her right to be happy, and the possibility of marriage to her equally meek boyfriend Nishimura (Kensaku Hara).

Being Asai’s mistress is perhaps not as bad as it sounds. Ayako is at least provided for – Asai pays her father’s debt and sets her up in an apartment they can use to conduct their affair but her status will always be uncertain. Asai’s wife (Yoko Umemura), ironically enough, is fond of Nishimura who may be something of a gigolo but their situation is unlikely to entail further consequences for either of them. In her relationship with Asai, Ayako begins meekly, playing the part-time wife which is exactly the figure Asai desires – someone to lovingly help with his coat and throw a scarf around his neck. When the affair is discovered by Mrs. Asai, Ayako’s character undergoes a shift. No longer meek and passive, she declares she will not see Asai again. Her physical presence and manner of speaking reverts to the repressed resentment previously seen only when dealing with her father.

If the failed affair allows a certain steel to rise within her, her neat kimono swapped for the latest flapper fashions, Ayako remains ill equipped to operate within the world she has just entered. About to renounce her “delinquent” life, Ayako fixes her hopes on reuniting with Nishimura and the normal, peaceful marriage to a kind and honest man that should have been hers if it were not for her father’s lack of care. Just when it looks as if she may triumph, a second familial crisis sends her right back into the world she was trying to escape but Ayako overplays her hand and suffers gravely for it.

Having sacrificed so much for her family, Ayako is rejected once again. Her feckless father and cruel siblings do not want to be associated with her “immoral” lifestyle which has made her a media sensation and continues to cause them embarrassment. She has lost everything – career, love, family, reputation and all possibility for a successful future. Yet rather than ending on the figure of a broken, desolate woman, Mizoguchi allows his heroine her pride. Ayako, far from collapsing, straightens her hat and walks towards the camera, facing an uncertain fate with resolute determination, defiantly walking away from the patriarchal forces which have done nothing other than conspired to ruin her.

Screened at BFI as part of the Women in Japanese Melodrama season. Screening again on 21st October, 17.10.

Also available on blu-ray as part of Artificial Eye’s Mizoguchi box set.

Opening scene (English subtitles)

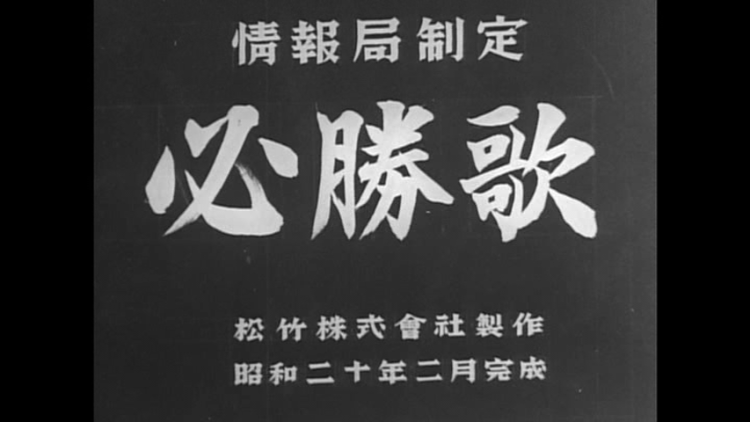

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles.

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles. Bunraku playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon had a bit of a thing about double suicides which feature in a number of his plays. Though these legends of lovers driven into the arms of death by a cruel and unforgiving society are common across the world, they seem to have taken a particularly romantic route in Japanese drama. Brought to the screen by the great (if sometimes conflicted) champion of women’s cinema Kenji Mizoguchi, The Crucified Lovers (近松物語, Chikamatsu Monogatari) takes its queue from one such bunraku play and tells the sorry tale of Osan and Mohei who find themselves thrown together by a set of huge misunderstandings and subsequently falling headlong into a forbidden romance.

Bunraku playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon had a bit of a thing about double suicides which feature in a number of his plays. Though these legends of lovers driven into the arms of death by a cruel and unforgiving society are common across the world, they seem to have taken a particularly romantic route in Japanese drama. Brought to the screen by the great (if sometimes conflicted) champion of women’s cinema Kenji Mizoguchi, The Crucified Lovers (近松物語, Chikamatsu Monogatari) takes its queue from one such bunraku play and tells the sorry tale of Osan and Mohei who find themselves thrown together by a set of huge misunderstandings and subsequently falling headlong into a forbidden romance.