The sudden arrival of a younger sister throws the despair and disappointment of an ageing chorus dancer into stark relief in Hiroshi Shimizu’s Dancing Girl (踊子, Odoriko). Chiyo (Machiko Kyo) is indeed a dancing girl, waltzing her way through post-war Japan with seemingly little thought for others or the consequences of her actions aware only of her ability to dazzle and what it might win her if used in the right way while her sister quietly yearns for a more comfortable, conventional kind of life.

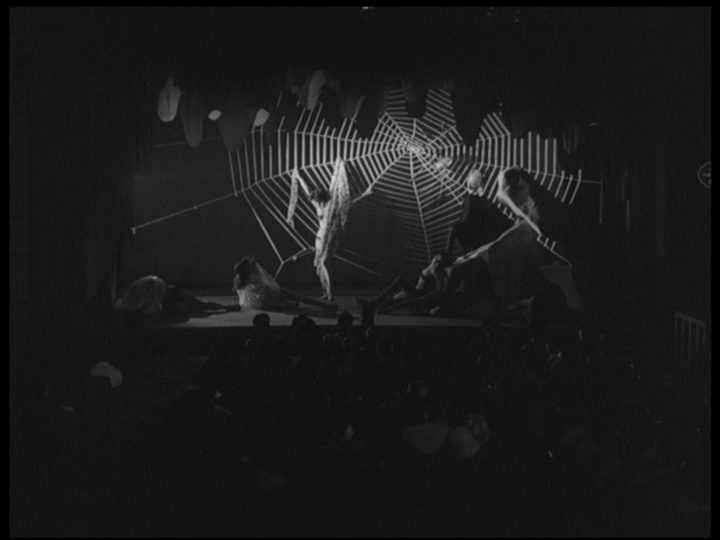

Hanae (Chikage Awashima) apologises for Chiyo’s childishness when she suddenly gets up to marvel at the snow during in an important meeting with choreographer Tamura (Haruo Tanaka) who has offered to take her on as a trainee dancer but he simply replies that it’s what makes her special in the way Hanae herself perhaps is not. In that sense there’s something a little uncomfortable in Tamura’s first word on meeting Chiyo being simply “sexy” uttered as if he were already salivating over her when the key to her appeal seems to lie in the awkward juxtaposition of her naivety and curvaceous figure. In many ways, it’s childishness that is Chiyo’s defining characteristic. She follows her impulses and is incapable of thinking beyond them. In a repeated motif we see her eat heartily as if she had not for eaten days or else to be snacking on something or other at a time when food is scarce. We later discover that she’s some kind of kleptomaniac, stealing at every opportunity even when she has no need to, simply taking something she wants without considering why it might not be right to do so as if all the world belonged to her. Meanwhile she embraces her sexuality without shame, sleeping with whomever she chooses but also doing so in a calculated effort to advance her own cause.

The irony is that her rise coincides with her sister’s fall. Hanae has passed the age at which she might have become a star and is beginning to age out of her career as a chorus dancer. She tells her husband, Yamano (Eiji Funakoshi), that what she wants is a comfortable life and to become a mother though the couple have been married for five years and not yet conceived a child leading her wonder if there’s medical issue in play though Yamano confesses in what turns out to be an ironic comment that he doesn’t really want children anyway. In any case, they are each becoming tired of life in Asakusa and their mutually unsatisfying careers. Crushingly they each fear they have disappointed the other, Hanae sorry that she never made it as a dancer and wondering if Yamano would have been better off marrying someone from a less stigmatised profession, while he feels guilty that he could not give her a better standard of life and has failed to progress in his own career as a violinist. Chiyo’s arrival reinvigates them both in different ways. Hanae shifts into a maternal mode otherwise denied her in looking after Chiyo as she begins her career as a dancer, while Yamano begins with her a sexual affair that rekindles his masculine drive.

But Chiyo also remains flighty and elusive. Essentially lazy, she soon tires of dancing and decides to become a geisha because it requires less rehearsal, then to give that up too to become someone’s second mistress. She rejects the conventional, settled life Hanae has come to long for and describes that in the countryside as “boring” when she suggests moving there having selflessly offered to adopt the baby Chiyo has also rejected which maybe Yamano’s or perhaps Tamura’s or someone else’s entirely not that it necessarily matters. The closing moments of the film perhaps imply a moralising rebuke of the new post-war vision of liberated sexuality, a despondent Chiyo once again making a surprise appearance and wanting to see her child but being afraid to do so unable to match up to the unsullied maternity of Hanae. Shimizu lends her passage a kind of transient quality in his restless camera which is in constant motion sliding laterally from one scene to another often coming to rest on emptiness even amid the bustling streets of a neon-lit Asakusa and the false promises of its illusionary glow.

Dancing Girl screens at Japan Society New York on May 18 as part of Hiroshi Shimizu Part 2: The Postwar and Independent Years.