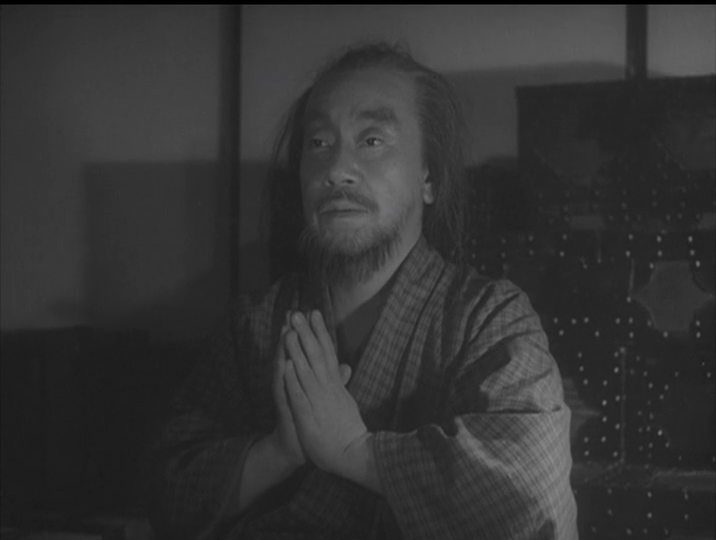

In the opening scenes of Hiroshi Shimizu’s Sound in the Mist (霧の音, Kiri no Oto), a young woman tells another that “as women, we need to create our own happiness,” though as it turns out it’s something that neither of them are really able to do. A classic melodrama, the film once again hints at Shimizu’s mistrust of romance and the frustrating inability of men and women to communicate or embrace their love for one another even when the seeming barriers preventing it have been removed.

To that extent, it’s interesting that the chief disagreement between unhappily married botanist Kazuhiko (Ken Uehara) and his wife Katsuyo is over her feminist politics and desire to devote herself to women’s emancipation under the new post-war constitution. The main bone of contention is that she wants to sell a mountain owned by Kazuhiko’s family to fund her political career though as he later says this mountain is his life. In any case he lets her sell it, believing there’s no point putting up a fight. He puts up even less of one in his relationship with Tsuruko (Michiyo Kogure), his assistant who is hopelessly in love with him yet after his wife’s angry visit decides to absent herself feeling as if she’s in the way.

It was her friend Ayako, a Tokyo dancer, who told her that women need to make their own happiness but in the end she couldn’t do it either. She was similarly involved with a weak-willed married man who continued to vacillate over leaving his wife offering the justification that he didn’t want to mess things up for his children. Eventually the pair find escape through double suicide which only emphasises the futility of their romantic connection. Tsuruko similarly makes several comments about the idea of death and dying, stating that if she were to die she’d want to go to a particular spot in the mountain which seems like heaven to her.

Though Katsuyo describes it as a “filthy” place the cabin does indeed become a kind of haven, a bubble of apparently chaste love and longing inhabited only by Kazuhiko and Tsuruko as the voiceover says hiding out from post-war chaos. Tsuruko seems to be the kind of woman Kazuhiko regards as the ideal wife in that she cares for him and supports his work even if he tells Katsuyo he just needed someone to run errands and do the grocery shopping so Tsuruko is there as his maid. Both are at pains to emphasise that no physical relationship exists between them but are otherwise prevented from acting on the their love because of Kazuhiko’s marriage along the existence of his daughter, Yuko (Keiko Fujita), who may be adversely affected by her parents’ decision to divorce in an age when such things were less common.

Kazuhiko continues to return to the mountain cabin which has since become an inn at regular intervals to see the Harvest Moon, as does Tsuruko though she also carries a degree of shame that makes her fear re-encountering Kazuhiko having become a geisha apparently solely to ensure her proximity to the mountain. Once again filming with the gentle lateral motion familiar from his later films, Shimizu focuses on the landscape and suggests that these lovers are only free to love in the natural world unconstrained by the petty concerns of civilisation which prevent them from embracing their desires. The sound in the mist is perhaps that of Kazuhiko’s latent romanticism and the implication that to him it may be better to suffer for love than to accept it. The same may be true for Tsuruko who is equally powerless if filled with regret that in the end she gave up so easily rather than fight for the love of her life.

On the other hand, the cabin seems to have given rise to a love match between Kazuhiko’s daughter Yuko and her husband who vow to continue the tradition of coming to the inn on the occasion of the Harvest Moon which marks both their wedding anniversary and the time they met. Yuko’s melancholy expression on coming to an understanding of her father’s “special memories” suggests a gentle sympathy but also that this younger generation is freer to love though no less romantic.The poignant closing scenes in which Kazuhiko wanders into the mist are nevertheless filled with irresolution, regret, and a longing that express only a deep sadness for the misconnections and misunderstandings of a less open past.

Sound in the Mist screens at Japan Society New York on May 23/30 as part of Hiroshi Shimizu Part 2: The Postwar and Independent Years.