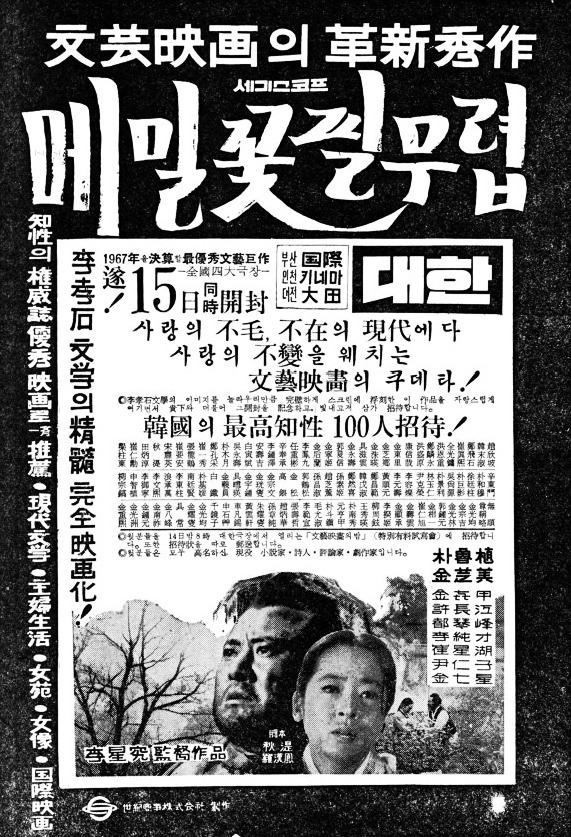

The false promises of the post-war era are brought home to two romantic youths dreaming of an illusionary future in Chung Jin-woo’s Green Rain (草雨 / 초우, Chou). At that time the youngest director to debut at just 25 years old with 1963’s The Only Son, Chung was a proponent of the “Cine Poem” movement which, in direct contrast to the literature film, sought to communicate through image alone minimising dialogue as much as possible. Heavily influenced by the French New Wave, particularly Godard’s Breathless and Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows, Green Rain is essentially an anti-romantic melodrama in which each of the lovers deceives and is deceived only to be awakened to the final truth that romantic salvation is nothing more than a childish fantasy.

Chung opens with an excitable sequence in which the heroine, Yeong-hui (Moon Hee), introduces us to her “home”, which is in actuality that of a diplomat who has just been appointed Ambassador to France and so is currently living in Paris. Yeong-hui had hoped that the family would take her with them, but Mrs Kim and her daughter who is suffering from an otherwise unexplained illness and uses a wheelchair, have been left behind alone and she with them. Yet Yeong-hui loves everything about the idea of Parisian sophistication, overexcited when a package arrives from abroad that turns out to contain the latest French fashions for the two Kim ladies. Yeong-hui looks on wide-eyed, but the daughter is petulant and resentful. She doesn’t want her father’s presents and views them as insensitive because it’s not like she has anywhere to show off nice clothes when she’s stuck at home ill. The two women debate giving the clothes away but can’t decide who best to give them to before Mrs. Kim casually offers Yeong-hui the stylish raincoat which is in its own way about to change her life.

As she later puts it, putting on the raincoat turns her into someone else. She waits eagerly for a rainy day and steps into a hip jazz club, somewhere she wouldn’t usually go, where she attracts instant attention precisely because of the coat. The women look on with scorn, noting the mismatch between the coat and the rest of her appearance, while the men swarm on her unpleasantly. Luckily, Cheol-su (Shin Seong-il) comes to her rescue and offers to drive her home believing that Yeong-hui is the ambassador’s daughter while she fails to disabuse him. He meanwhile tells her he’s a chaebol son, but really he’s a mechanic and sometime university student currently in a compensated relationship with a stylish older woman who we later learn to be some kind of gang leader.

They fool themselves into thinking they’re falling in love, deceiving themselves as well as each other in playing at innocent romance. They meet every time it rains and go on charmingly innocent dates to parks and boating lakes shot with a dreamy romanticism, but also, in contrast to Barefooted Youth, indulge in stereotypically “low” forms of entertainment such as boxing and horse races without ever managing to blow their covers as they simultaneously both pretend to like Tchaikovsky because they’re trying to live up to an image of upperclass sophistication.

Yet, there are cracks in their connection. They talk idly of the kind of future they’ll have with Cheol-su wanting an “enormous concrete home” while Yeong-hui claims she’s fine with somewhere small so long as there’s sunlight because she wants her life to be “real, not for show”. It’s an ironic statement under the circumstances, one which is perhaps brought home to her by the otherwise kindly old washerwoman across the way who is forever complaining about her “fake” coal that won’t light and moans about “fakes passing themselves off as the real thing”. Yet she continues to believe in her fairytale romance with Cheol-su, even while declaring it to seem “like a dream”, terrified that he’ll find out she’s just a maid and leave her. He, meanwhile, is less invested in the idea of romantic love, describing her first as a “business opportunity”. On their first meeting he finishes with the older woman, drops out of the “third class uni” he thinks is more trouble than it’s worth, and continues to push his luck with his boss by repeatedly “borrowing” customers’ cars because he thinks he’s on to a sure thing with the ambassador’s daughter and no longer needs to worry about keeping the job. He presses his friends for money, pawns everything he can get his hands on, buys a fancy suit and tries to convince Yeong-hui he’s upperclass only to be pushed into a corner when she declares she wants fancy crockery in her simple home. To get his dream life, Cheol-su commits a robbery only to be surrounded by an angry mob a la Bicycle Theives and receives the first of many beatings.

This sense of frustrated humiliation might explain the unexpectedly traumatic closing scenes which contrast so strongly with gentle romanticism with which the film opened. Cheol-su risked everything for a mistaken ideal and he’s failed. He realises Yeong-hui has been deceiving him too, but rather than a cute romantic resolution that returns them both to the grounding of their original social class, he reacts with hypocritical rage and anger. Yeong-hui reemphasises that she loves him anyway, clinging fast to her dream of love, but he ruins her, consumed by toxic masculinity in his sense of hopelessness and inferiority as a working class man with no prospect of improvement now that his dream of marrying up has dissolved. In another film he might be the hero, reinforcing duplicitous ideals of societal misogyny, but in this one he is the fool and the villain. “Without an ounce of sorrow I understood what it was to be a woman” Yeong-hui adds bitterly, finally understanding her romantic fallacy for what it was, learning a painful lesson in naivety and self-deception and striding boldly back to her old life, wiser if perhaps less hopeful whereas Cheol-su runs away still chasing an easy fix to a more prosperous future. At once a criticism of the increasingly consumerist society, its deeply entrenched social inequalities, and its patriarchal social codes, Green Rain is most of all an anti-romantic melodrama in which love is nothing more than childish fantasy incapable of offering salvation in a world of constant impossibility.