What is it that binds a “family”, bonds or blood, and do you really have a choice when it comes to being in one? Those are all questions which might have greater import in societies in which the concept of family is clearly defined and deeply entrenched, but even so the answers may be in a state of flux in the face of rapid social change which perhaps dangles the possibilities of greater personal freedom while in other ways remaining rigidly conservative.

More literally translated as the birth of a family, Kim Tae-yong’s Family Ties (가족의 탄생, Gajokeui tansaeng) explores these changing connections through three interconnected stories, the first two occurring roughly contemporaneously and the third around a decade later. The heroine of the opening chapter, Mira (Moon So-ri), is a reserved young woman running a small cafe mostly catering to noisy teens. Originally excited to receive a phone call from her younger brother Hyung-chul (Uhm Tae-woong) whom she hasn’t seen for five years letting her know he’ll be coming home for a visit, Mira’s enthusiasm for the reunion dwindles when he turns up with a new wife, Mu-shin (Go Doo-shim), who appears to be much older than him. Mira is understandably put out. Firstly, he obviously didn’t invite her to his wedding, in fact he didn’t even bother to share the news he’d got married, and secondly it’s quite inconsiderate not to have warned her there would be an extra guest in tow especially as they’ve not met before.

On the other hand, perhaps seeing him again merely reminds her of all the reasons they haven’t stayed in touch. In a quiet moment, Hyung-chul reveals he wants to open a shop selling traditional hanbok nearby, which is a surprise, but Mira instantly realises he’s probably come for money and repeatedly tells him she doesn’t have any. When everyone’s asleep, she makes a point of putting her bank book in a locked box inside the safe just to be sure he won’t abscond with it in the night. With Hyung-chul picking a fight with her fiancé and a random child turning up who turns out to be Mu-shin’s unwanted stepdaughter from several relationships ago, Mira’s patience begins to come to an end. She suggests that perhaps they’ve outstayed their welcome, but then evidently thinks better of it only to be let down once again by her irresponsible brother who claims he can take care of everyone, but predictably does not follow through.

Family becomes a burden left to women to bear while acting as a safety net for men who view their role as protector yet largely can’t look after themselves. Sun-kyung (Gong Hyo-jin), the slightly younger protagonist of the second story, is frustrated by this same self sacrificing quality in her mother who has been continually deceived by useless lovers all her life including the most recent, a married man who won’t leave his wife and children. She also resents the presence of her much younger brother, still an elementary student doted on by the mother from whom she feels increasingly disconnected. Having run away from home to become a singer, Sun-kyung now has her sights set only on escaping abroad and is currently working as a guide for Japanese tourists only to end up bumping into her ex-boyfriend on a day out with his new partner. For her family is little more than a trap, her boyfriend apparently breaking up with her for being too selfish while she eventually pays a visit to the home of her mother’s lover to confront him and ask if “love” is really worth the price of sneaking around living a lie. Yet bonding with her brother and discovering what was in the mysterious suitcase her mother insisted on leaving at her apartment perhaps reconnects her with her childhood self and a more positive take on family bonds, even if that means in a sense regaining one dream only to abandon another.

In any case, the anxieties of the first two sequences are visited in the third through the story of a young couple we first meet sitting next to each other on a train. So familiar with each other are they that we assume they are already involved, but they are in fact strangers meeting for the first time. Flashing forward a little, however, we can see their relationship is strained. Kyung-seok (Bong Tae-gyu), the young man, has inherited a sense of male insecurity, flying into jealous rages ostensibly because his girlfriend Chae-hyeon (Jung Yu-mi), is simply too nice or more to the point she’s nice to everyone and not just to him. He is frustrated by her because he feels she allows herself to be taken advantage of, often lending money to people who won’t see the need to pay her back because she’s too “nice” to bring it up. The last straw comes when he feels she’s embarrassed him by not showing up for a family dinner because she got involved in the search for a missing child.

“When I’m with you I’m dying of loneliness” he somewhat dramatically announces as part of a breakup speech, annoyed that Chae-hyeon does not devote herself entirely to him as perhaps he expects a woman to do, but defiantly carries on being indiscriminately nice to everyone. He describes his mother as “pathetic” for having been overly attached to unreliable men, only to be corrected by his sister who reminds him that she merely had a big heart, something he’s perhaps lacking in his broody neediness. Yet through meeting Chae-hyeon’s family we get a sense of something different and new in which two women have raised a child unrelated to them by blood who came into their lives by chance as the result of a man’s irresponsible behaviour, an unnecessary throwaway reference to separate bedrooms perhaps undermining the boldly progressive introduction of Chae-hyeon’s two mothers to the extremely confused Kyung-seok. Nevertheless what we see in this last family, born as it was through a series of accidental meetings, is the first instance of a warm and loving home built on mutual support and affection rather than simply on blood or obligation. Having reclaimed the nature of family for themselves perhaps gives the women the courage and conviction to firmly close the door on those who might seek to misuse or corrupt it with their own sense of selfish entitlement, blood relation or not.

Family Ties streamed as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

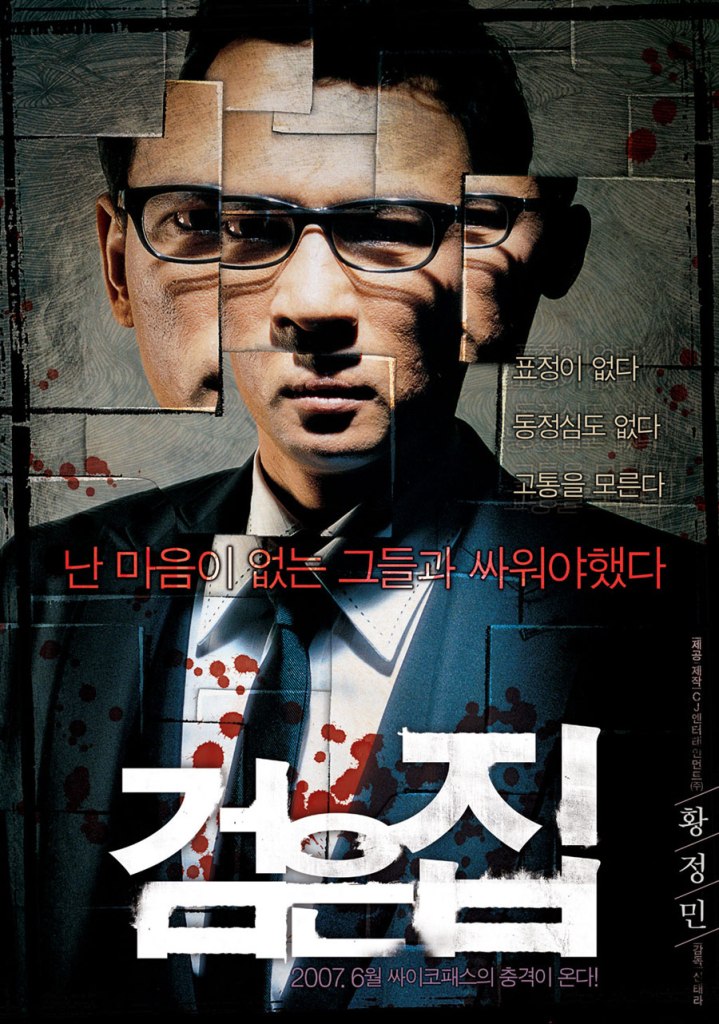

Yusuke Kishi’s Black House source novel was

Yusuke Kishi’s Black House source novel was