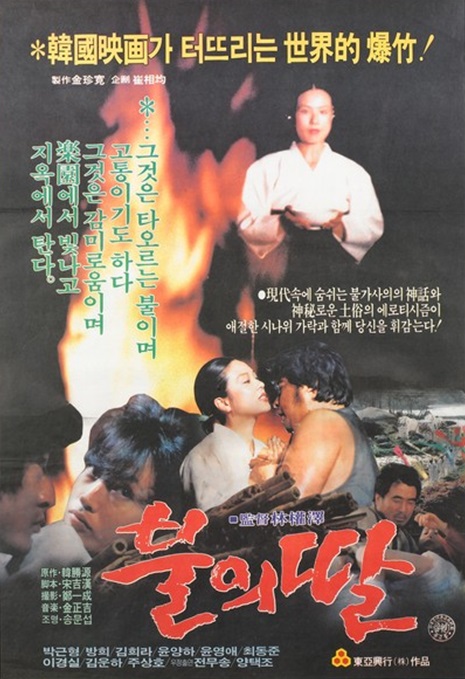

“Doctor, is it possible in our modern society for someone to suffer from that kind of illness?” the conflicted hero of Im Kwon-taek’s Daughter of Fire (불의 딸, Bul-ui ttal) asks his psychologist, plagued by nightmares of the mother who abandoned him at 11 and suffering what seems to him to be the call to shamanism, only what place could such a backward and superstitious practice have in “our modern society?”. In many ways, it’s exactly that question which Im seems to find so essential, implying in a sense that even in the politically repressive but increasingly prosperous Korea of the late ‘70s that they have perhaps lost something of their essential Koreanness in their abandonment of their ancestral beliefs in favour of modern “sophistication”.

Listening to his troubles, the disinterested psychiatrist reassures Hae-joon that it’s just a “minor neurosis” caused by “frustration” which can easily be cured. On his way home, however, Hae-joon is accosted by an older woman dressed in shaman’s clothing who addresses him as a son, reminding him that he has the blood of shamans running in his veins and try as he might he’ll never be able to escape it. Her intervention perhaps links back to an earlier encounter with the pastor at his wife’s church who explained to him that his wife is at the end of her tether, embarrassed by his lack of faith believing that it reflects badly on her as a religious woman hoping to lead others towards the lord if she cannot at least count her husband among the saved. So great is her distress that she has apparently even considered divorce. This is perhaps one reason Hae-joon is so keen to exorcise his shamanistic desires, though it’s also clear that his presence in his home is intensely resented, his wife later only warmly greeting him by hoping that he’ll be able to let go of his “dark and diabolical life” for something brighter and more cheerful, ie her religion though the grey uniformity and intense oppression of her practice only make her words seem more ironic.

The pressing problem in his family is that his daughter is also sickly, seemingly with whatever it is which afflicts Hae-joon. She has begun sleepwalking and later suffers with fits and seizures which to a certain way of thinking imply the onset of her shamanistic consciousness. Hae-joon’s Christian family, in a touch of extreme irony, are convinced that an exorcism in the form of a laying on of hands will cure her, yet they like many others view the ritualised religious practice of the shaman as a backward relic of the superstitious past. The ironic juxtaposition is rammed home when Hae-joon is sent to cover a supposed miracle for his newspaper that his wife and her friends from church regard as the second act of Moses, standing ramrod straight and singing hymns while a noisy festival of shamanic song and dance occurs further along the beach apparently a rite to appease both the sea god and the vengeful spirit of an old woman accidentally left behind when her community migrated to another island to escape an onslaught of tigers. Stuck in the middle, Hae-joon exasperatedly explains to his photographer that this parting of the seas isn’t any kind of miracle at all, merely a natural result of low tide revealing that which would normally be hidden.

Yet despite his unsatisfactory visit with the psychologist, Hae-joon becomes increasingly convinced that only by finding his mother can he come to understand what it is that afflicts him. Speaking to the various men who knew her from the step-father he later ran away from to escape his abuse after his mother disappeared, to a blacksmith who cared for him as an infant, and the men she knew after, Hae-joon begins to understand something of her elemental rage. Driven “mad” by the murder of her lover by the Japanese under the occupation, she wandered the land looking for fire to exorcise her suffering only later to lose that too when the oppressive Park Chung-hee regime outlawed shamanism entirely in his push towards modernity. Consumed by the fires of the times in which she lived, there was no place in which she could be at peace and nor will there be for Hae-joon or for his daughter until they embrace the legacy of shamanism within.

“Shamanism will not disappear and die” Hae-joon later adds, now able to see that there is or at least could be a place for it in “our modern society” or perhaps that it’s the modern society which must change in order to accommodate it. Despite his long association with depictions of Buddhism, it is the shaman which Im considered the foundation of Korean culture, something he evidently thinks in danger to the perils of a false “modernity”, Hae-joon eventually professing his concerns that without it Korea will forever be oppressed by foreign influence. Only by accepting the shaman within himself can he hope to find freedom in an oppressive society.

Daughter of Fire streams in the UK until 11th November as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.