Naomi Kawase had provoked a minor upset with her unexpected Grand Prix win for 2007’s The Mourning Forest and has since earned a reputation as a festival darling. Her followup film, 2008’s Nanayo (七夜待, Nanayomachi), however, failed to make much of an impact in the international festival scene and seems to have been more or less forgotten, considered among the most minor of Kawase’s disparate filmography. In some ways it picks up where The Mourning Forest left off as a young woman looks for meaning in the primitive beauty of nature, but it’s also a major departure in being the first of her films made outside of Japan and dealing with far broader themes from her familiar focus on familial disconnection to oblique references to the traumatic legacies of colonialism and the inefficiency of language as a tool for communication.

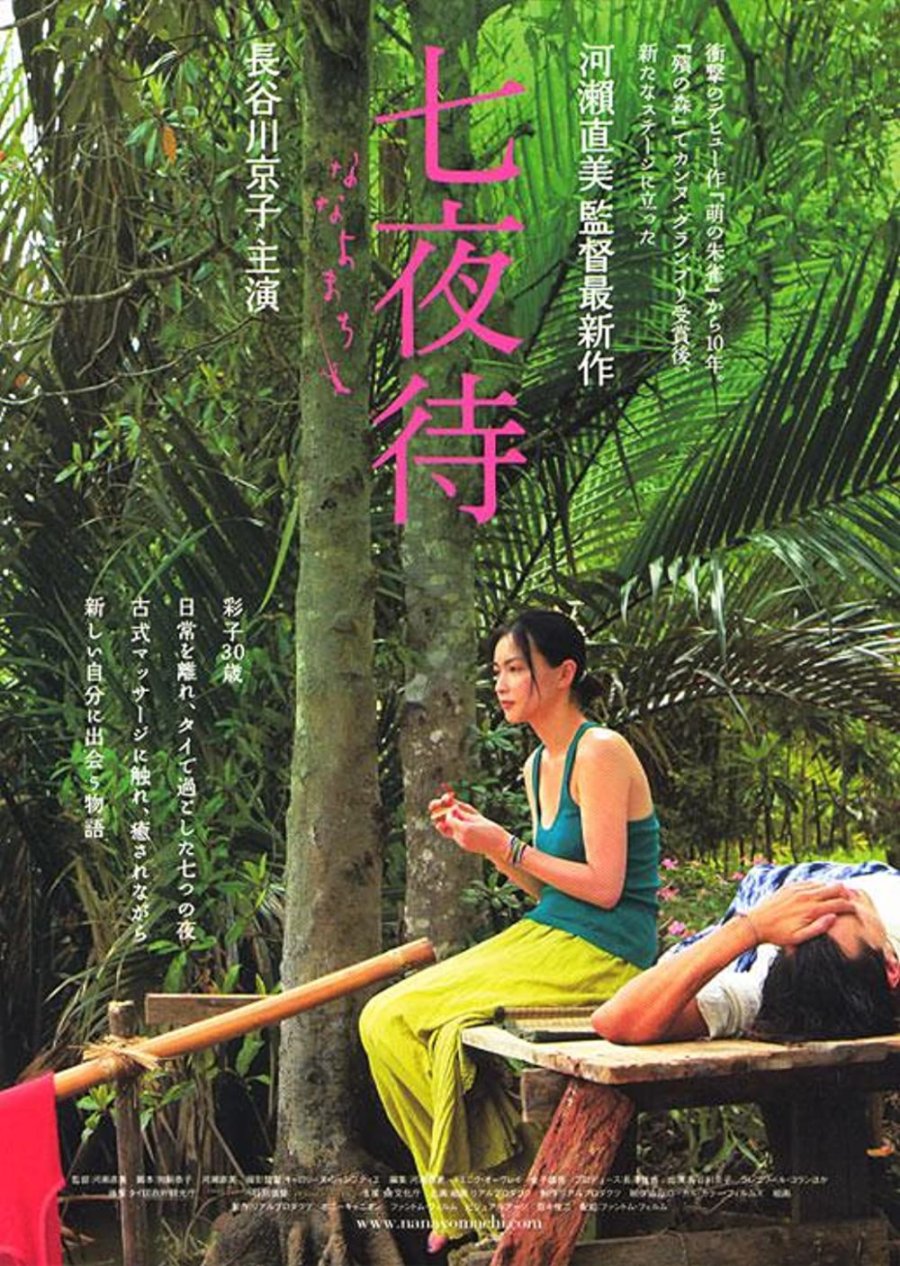

The heroine, Saiko (Kyoko Hasegawa), arrives in Thailand it seems without much of a plan or a clear idea of where she’s going. Largely unable to communicate in any language other than Japanese, she wanders around lost looking for her hotel until someone is able to explain to her that she’s in completely the wrong place, and as the hotel is too far to walk she’d best take a taxi. The taxi driver, however, can’t understand her either but for some reason agrees to take her. Saiko falls asleep and wakes up sometime later to realise he’s driven her out to the middle of nowhere, belligerently insisting she get out of the car. Understandably fearing the worst, she manages to dodge past him and run off into the forest leaving her bags behind. Eventually she encounters a random Frenchman, whom she can’t understand either, who takes her back to the small guest house he’s staying at to learn Thai massage. Later the taxi driver, Marwin (Netsai Todoroki), turns up too and in a weird coincidence it turns out that he’s the brother of the woman running the massage school, Amari (Kittipoj Mankang).

Despite having no common language, the four of them along with Amari’s half-Japanese son Toi (which in Japanese anyway means “far”) become an odd kind of family, relying on universal human gestures in an effort to communicate. To this extent, it is perhaps a shame that the film is subtitled in that the impossibility of true understanding through verbal communication seems to be a key theme. At one point, Frenchman Greg (Grégoire Colin) opens up to Saiko about his reasons for coming to Thailand, that he’d been in denial of his homosexuality and is finally beginning to accept himself. Perhaps he tells her precisely because she will not understand, but it’s an immense irony that her first question is to ask if the pretty bracelet on his wrist was a gift from a girlfriend. In their shared mix of broken English, she thinks he’s saying “lovely” when he’s really just trying to say that it looks like rain.

Meanwhile, Amari has some Japanese, presumably learnt from Toi’s absent father of whom she gives no further details. Marwin later implies that she met him through some kind of sex work, and we later see him fall out with his daughter over something much the same in accusing her of being in a compensated relationship with a foreigner while she fires back that it’s none of his business seeing as he failed as a father in proving unable to support her financially. When Saiko makes the perhaps unwise decision to get in Marwin’s cab, it’s in the process of being vacated by a drunk and extremely rude Englishman who yells some vaguely racist abuse at him and then walks off with a Thai beauty. The prevalence of sex work appears as an extension of contemporary colonialism, something of which both Greg and Saiko may be accidentally guilty in coming to Thailand to look for something as nebulous as spiritual awakening, beckoned in by orientalist notions of Eastern mysticism. Amari, while never resenting Saiko, perhaps sees in her an echo of her absent lover, repeatedly asking her son if he’d want to meet his father or to visit Japan. The climactic fight which emerges seemingly out of nowhere is fought over Amari’s decision to send Toi to a temple to train as a monk, affirming that Saiko wouldn’t understand because her country is “beautiful and rich”, explaining that she wants her son to grow up rich spiritually not to be materialistic, though Saiko herself describes Japan only as “peaceful” lacking the warmth that she feels in the Thai people.

Saiko of course cannot understand because she has absolutely no idea what anyone is saying, realising only that Toi has gone missing and everyone is so intent on arguing in several languages that no one’s bothering to look for him. She doesn’t understand why everyone’s shouting at her when she’s only a bystander, perhaps another comment on the legacy of colonialism, while to Marwin it seems obvious that the boy’s run off because he doesn’t want to be a monk and is sad thinking his mum doesn’t want him anymore. When Saiko finds him, it seems that he’s particularly preoccupied with whether or not his father loved his mother, perhaps beginning to understand the complexities of his birth and his dual nationalities.

Once again adopting an elliptical structure, Kawase builds slowly towards the scenes which opened the film in which Toi and Marwin prepare to enter the temple as monks, the moment attaining a kind of spiritual catharsis which seems at odds with the conflicts of the preceding scenes which asked if Amari was right to separate from her son and force him to become a monk against his will. The temple scene is followed by a ritual dance similar to that in Shara in which Saiko seems to cast off her gloominess in spiritual release, building on earlier scenes in which she idly fantasised about intimate massages from a Japanese monk (Jun Murakami) apparently achieving an entirely different kind of enlightenment. Touch, Kawase seems to say, is the only true communication, leaving it to former soldier Marwin to expound on how we’re all different and speak different languages but we should love each other rather than kill in war. There is danger everywhere he explains, though Kawase’s gentle pan to the tranquility of life on the wide river might seem to contradict him.

Trailer (no subtitles)