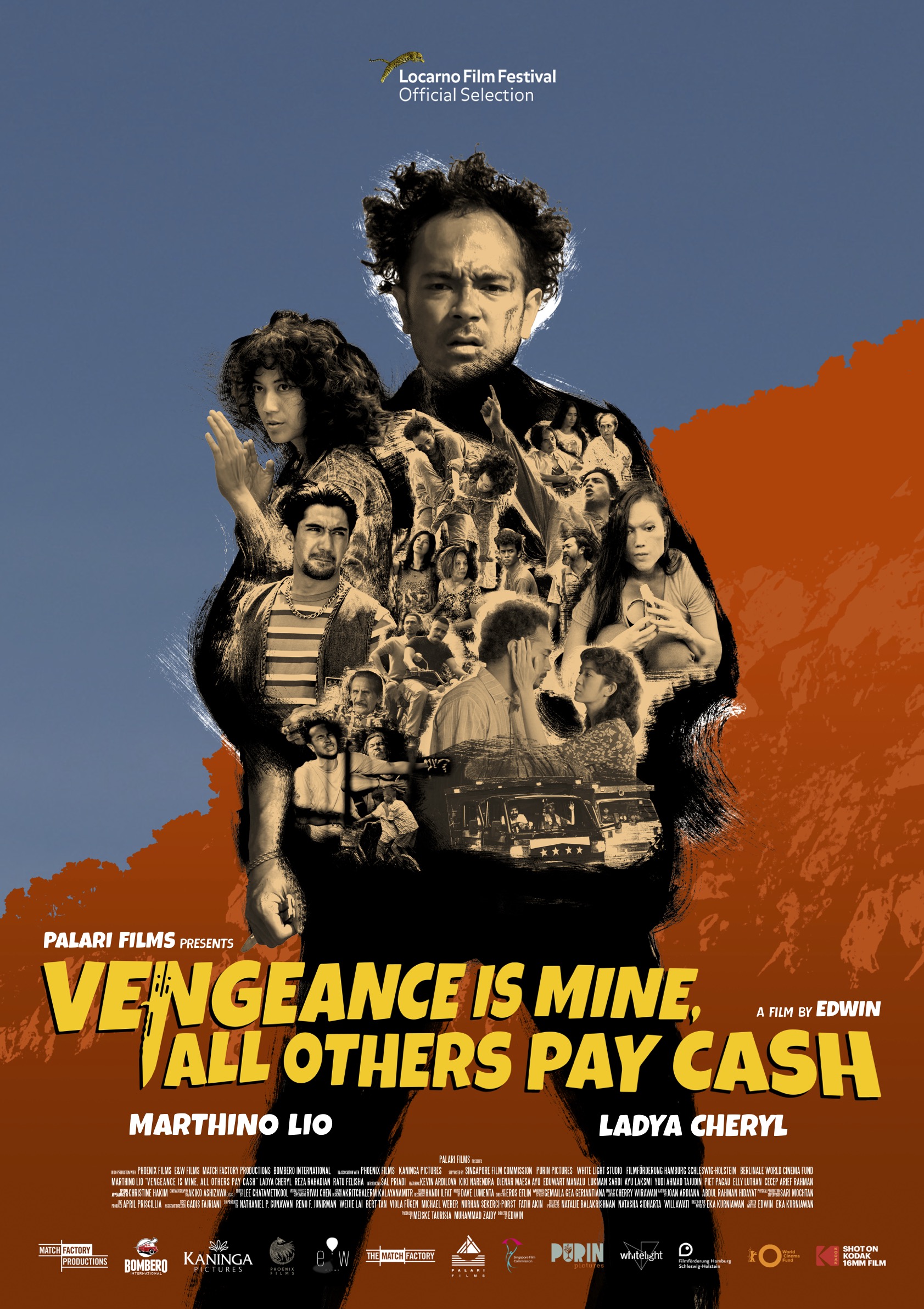

The innocent love of a pair of traumatised youngsters is crushed by the society in which they live in Edwin’s ‘80s-set pulp adventure, Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash (Seperti Dendam, Rindu Harus Dibayar Tuntas). An absurdist parable about the corrosive effects of toxic masculinity and its links to oppressive authoritarianism, Edwin’s outlandish drama sees a young man contend with literal and societal impotence through the medium of violence while falling in love with a woman equally in desire of revenge against her misuses at the hands of a misogynistic society.

Rendered sexually impotent after childhood trauma, 20-something Ajo (Marthino Lio) gets his release through violence well known for always being up for a fight whether there’s money involved or not. Yet as we see he seems to enjoy being on the receiving end, almost giggling when he’s set upon by a small mob in a bar. During the course of one particular job with a social justice angle roughing up an overreaching local businessman who apparently pressed a man into debt in order to extract the payment from his wife, Ajo ends up running into Iteung (Ladya Cheryl), his target’s bodyguard and a lover of violence like himself. The pair fall in love, but Ajo is afraid to pursue a relationship because of his impotence eventually provoked into a rain-soaked confession only to realise that just like everyone else in town Iteung already knows and doesn’t care. She marries him anyway but is continually stalked by a resentful ex, Budi (Reza Rahadian), while Ajo is preoccupied with a job he unwisely took on to knock off a gangster rival of former general Uncle Gembul (Piet Pagau).

The pair are in a sense pursued by their pasts each of which stems back to an instance of sexual abuse, the young Ajo forced to participate in a rape after being kidnapped by a pair of corrupt soldiers and thereafter rendered impotent. In an ironic touch, the assault takes place on the day of an eclipse which president Suharto had issued advice not to look at owing to the possibility of damaging one’s sight though in essence Ajo gets in trouble for looking directly at something he should not have seen and is rendered impotent by corrupt state power. Years later, Iteung decides she wants revenge, that if she could track down and enact justice on these two former soldiers she might be able to lift Ajo’s curse and ironically enough restore his manhood so that they might have a full marriage.

She meanwhile is also carrying her own trauma having been subject to male sexualised violence from a young age. Given Ajo’s condition, the pair consummate their relationship through pugilism, a fight scene standing in for sex but the disruptive presence of the brooding Budi continues to linger on the horizon Iteung coming to regret a bargain she made with him in the hope of tracking down the soldiers. Having quelled his lust for violence, discovering that Iteung has betrayed him sends Ajo into a murderous rage finally completing the job he had been afraid of doing in fear that it would pollute his otherwise blissful relationship with his new wife. In an ironic touch, Budi’s big business plan is selling a snake oil male virility tonic, his insecure yet superficially powerful vision of masculinity held up as an ideal while Ajo once again attempts to validate his manhood through violence. After a period of wandering and an encounter with a mysterious figure he begins to rediscover a sense of security in masculinity that is not linked with sexuality realising that all he wants is to be with Iteung and he no longer cares whether or not his impotence is ever cured.

A retro homage to the action exploitation movies of the 1980s, Edwin’s absurdist world building is a direct attack on a macho culture that manifests itself in oppressive authoritarianism along with the concurrent misogyny that leaves women vulnerable to male violence. At heart a romance in which love ultimately triumphs over the corrosive effects of toxic masculinity and entrenched patriarchy, Edwin’s absurdist tale later takes a turn for the metaphysical in the form of the arrival of a ghostly avenger come to enact justice on those who presumed themselves above the law but nevertheless ends on a note of cosmic irony in which the wages of vengeance must indeed be paid in full.

Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash screens in New York March 19 with lead actress Ladya Cheryl appearing in person as part of Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look 2022. Due to popular demand, a second screening without guest appearance has now been added on March 26.

International trailer (English subtitles)