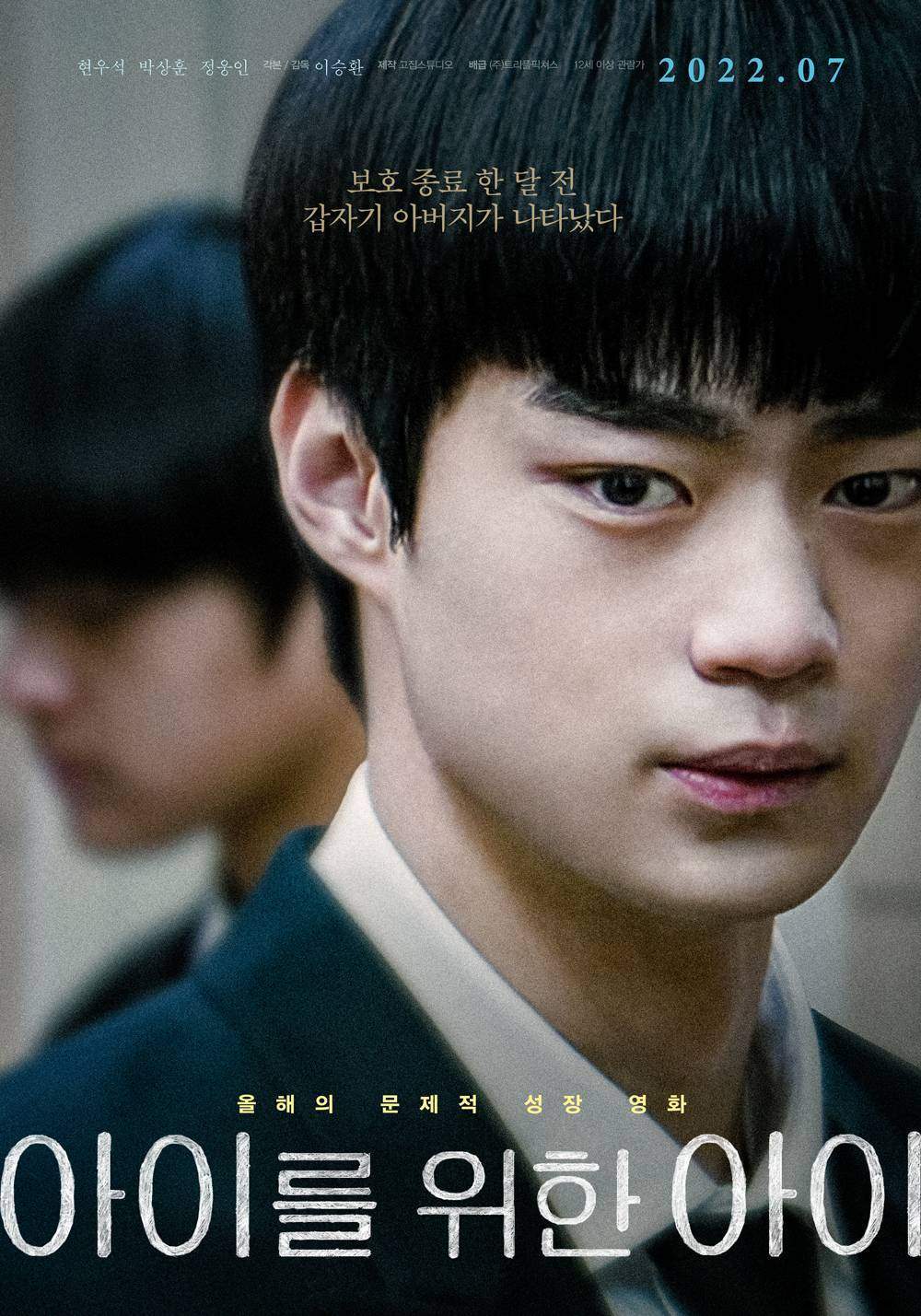

Unexpectedly reunited with his estranged father, a young man is confronted with a series of choices on leaving the care system in Lee Seung-hwan’s darkly comic coming-of-age drama A Home from Home (아이를 위한 아이, Ayireul Wihan Ayi). The Korean title may mean something more like a child looking after a child, but the English also neatly encapsulates the hero’s dilemma on being ejected from the orphanage where he has lived for most of his life into a new “family” home with two strangers he hardly knows at all.

Do-yun (Hyeon Woo-Seok) is about to come of age. In less than a month he will have to leave the orphanage where he lives and has nowhere else to go. Working as a takeaway delivery driver, he is acutely aware of the prejudice directed towards those who have no families with both his boss and unreasonable customers making jibes about how they expect no better from someone who “wasn’t raised properly”. Prejudice is one reason he longs to leave Korea for the promise of Australia, explaining that there he’ll simply be “Korean” rather than an “orphan” and will be able to build an independent life for himself. All his plans are scuppered, however, when a man turns up at the orphanage claiming to be his estranged father and offering to take him in.

Understandably resentful, Do-yun is persuaded to accept the offer and discovers that he has a younger half-brother, Jae-min (Park Sang-Hoon). Seung-won (Jung Woong-In), his father, claims that he gave up Do-yun for Jae-min wanting to remarry after his first wife died but apparently unable to take his first son with him. That might be reason enough to resent Jae-min, but Do-yun doesn’t particularly only wanting to save enough money to get to Australia and leave the family behind. The problem is that Seung-won soon passes away leaving Do-yun with a still deeper sense of loss and resentment while wondering if Seung-won only returned to claim him because he needed someone to look after Jae-min in his absence. Only 20 years old, he ends up becoming Jae-min’s guardian and despite himself decides to put his Australian dreams on hold to look him.

Becoming an accidental “father” so young does indeed force Do-yun to grow up quickly, learning to cook (well, divide a microwave dinner onto plates) and keep the apartment Seung-won left them tidy. Perhaps he’d have had to figure all that out for himself alone on leaving the orphanage and having to manage on his wages from the delivery job, but there is also a lingering resentment that he’s putting his life on hold for a “brother” he didn’t know until a few weeks previously wondering what sort of responsibility he really bears for him even as he begins to ease into a sense of familial comfort he had never known before. Even so, an unexpected revelation sees him questioning himself further and trying to figure out whether he really belongs with Jae-min at all or should cut his losses and go to Australia anyway.

In an odd way, he comes to view his new familial relationship as “just another prison” while jealous of Jae-min’s opportunities and yearning for independent freedom. Meanwhile, he finds himself targeted once again by exploitative adults in the form of a gold-digging aunt and her obnoxious husband intent on getting their hands on Jae-min’s inheritance, and scammed out of money he’d saved for his new life abroad by another “brother” he’d grown up with in the orphanage. What he wants is to make a decision that’s his own rather than being railroaded by the circumstances of his life or manipulated by forces beyond his control but also begins to develop a genuine familial connection with Jae-min even while remaining mildly distrustful and trying to figure out where it is that he truly belongs. Exploring the effects of a societal prejudice against orphanhood as well as the practical and emotional difficulties faced by those who are abruptly ejected from the care system into an uncaring world, Lee’s strangely cheerful drama finds two young men searching for support but finally discovering they may have only themselves to rely on.

A Home from Home streams in the US until March 31st as part of Asian Pop-Up Cinema Season 16.

International trailer (English subtitles)