Chinese cinema, it could be said, has been looking for the road home for quite some time. Not only is the past a relatively safe arena for present allegory, but even among the previously hard edged fifth generation directors, there’s long been a tendency to wonder if things weren’t better long ago in the village. Zhang Yimou certainly seems to think they might have been, at least in the beautifully melancholic The Road Home (我的父亲母亲, Wǒde Fùqin Mǔqin) in which a son returns home after many years away and reflects on the deeply felt and quietly passionate love story that defined the life of his parents.

Chinese cinema, it could be said, has been looking for the road home for quite some time. Not only is the past a relatively safe arena for present allegory, but even among the previously hard edged fifth generation directors, there’s long been a tendency to wonder if things weren’t better long ago in the village. Zhang Yimou certainly seems to think they might have been, at least in the beautifully melancholic The Road Home (我的父亲母亲, Wǒde Fùqin Mǔqin) in which a son returns home after many years away and reflects on the deeply felt and quietly passionate love story that defined the life of his parents.

In the late ‘90s, a successful businessman, Luo Yusheng (Sun Honglei), drives back to his rural mountain village on hearing of the sudden death of his father, Changyu (Zheng Hao ) – a school teacher. The village’s mayor explains to him that for some years his father had been desperate to improve the local school and, despite his advanced age, had been travelling village to village raising money until he was caught in a snow storm and taken to hospital where they discovered he had heart trouble. The mayor wanted to pay for a car to fetch Changyu, but Yusheng’s mother Zhao Di (Zhang Ziyi) wants him to be carried back along the road to the village in keeping with the ancient tradition so he won’t forget his way home.

The problem, as the mayor points out, is that like Yusheng, most of the other youngsters have left the village and there just aren’t enough able-bodied people available to make Zhao Di’s request a realistic prospect. Zhang’s film is not just a warm hearted love story, but a lament for a lost way of life and a part of China which is rapidly disappearing.

This fact is poignantly brought home by Yusheng’s realisation that his parents’ love, set against one kind of political turbulence, was a kind of revolution in itself. In the Chinese countryside of the 1950s, marriages happened through arrangements made by (generally male) family members, no-one fell in love and then decided to spend their lives together. Yet Zhao Di, a dreamy village girl whose own mother was so heartbroken by the death of her husband that she was blinded by the strength of her tears, dared to believe a in romantic destiny and then refused to accept that it could not be.

Zhang begins the tale in a washed out black and white narrated by the melancholy voice over of the bereaved Yusheng whose first visit home in what seems likes years is tinged with guilt and regret. His father wanted him to be a teacher in a village school, but Yusheng left the village and like most of his generation took advantage of changing times to embark on a life of wealth and status in the city. As remembered by their son, the love story of Zhang Di and Luo Changyu is one of vivid colour from the freshness of the early spring to the icy snows of winter.

An innocent love, the courtship is one of sweet looks and snatched conversations. Zhao Di, captivated by the new arrival, listens secretly outside the school and waits for Changyu on the “road home” as he escorts the children back to the village. Yet these are turbulent times and even such idyllic villages as this are not safe from political strife. The burgeoning romance between a lonely village girl and earnest young boy from the city is almost destroyed when he is ordered back “to answer some questions” for reasons which are never explained but perhaps not hard to guess. Zhao Di chases him, the totality of her defeat crushing in its sense of finality but again she refuses to give up and remains steadfast, waiting for her love to reappear along the road home.

Though “the road home” carries its own sense of poignancy, the Chinese title which means something as ordinary as “my mother and father” emphasises the universality of Yusheng’s tale. This is the story of his parents, a story of true and enduring love, but it could be the story of anybody’s parents in a small rural village in difficult 1950s China. The world, Zhang seems to say, has moved on and consigned true love to an age of myth and legend while the young, like Yusheng, waste their lives in misery in the economic powerhouses of the city never knowing such poetical purity. China has been away too long and lost its way, but there will always be a road home for those with a mind to find it.

International trailer (English voiceover)

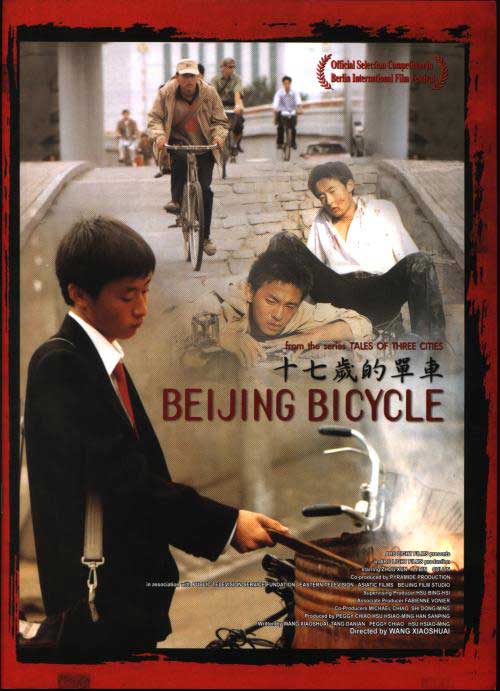

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.