“Those are the rules of the palace for a princess” the rebellious heroine of Choi Eun-hee’s second directorial feature A Princess’ One-Sided Love (公主님의 짝사랑 / 공주님의 짝사랑, Gongjunimui Jjaksarang) is told, though the “palace” is really the society and the “rules” those which all women are expected to “endure”. Quietly and perhaps subversively feminist, Choi’s humorous tale draws inspiration from Roman Holiday but unexpectedly engineers a happier ending for its lovelorn heroine who is permitted to transcend the constraints of her nobility if not quite of her womanhood.

Tomboyish princess Suk-gyeong (Nam Jeong-im) is the youngest of six princesses and the last to remain at home in the palace yet to be married. Consequently, she is infinitely bored all the time and continually up to mischief in part because as a princess she is not permitted to leave the estate and has a natural curiosity about the outside world. That curiosity is further sparked when she lays eyes on handsome scholar Kim Seon-do (Kim Gwang-su) who picks up a shoe she had dropped while inappropriately running on the day of her mother’s birthday celebrations. Possibly the first young and handsome man she has even seen, Suk-gyeong cannot help but be captivated by him and manages to convince her sisters to help her escape the palace to venture in search of her probably impossible love under the pretext of visiting her grandparents whom she has apparently never visited before.

Like Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday, what Suk-gyeong wants is a break from the “tedious and pathetic” life of a princess, but soon discovers herself to be entirely naive as to how the “real world” works. Her sisters agreed to help her in part because they acknowledge how difficult it was for them when they married and had to leave the palace with no understanding of how to live outside it. Having left in the clothes of a servant, the first thing that Suk-gyeong realises is that the outside world is governed by a different set of hierarchies and even if she’s a princess she is still a woman and therefore presumed to be “inferior” to men to whom she is expected to remain subservient. Her grandfather, who has never met her before, wastes no time exerting his patriarchal authority in his own, comparatively humble, home. “A woman, once married, must abide by the rules of her new family, the confucian ethics, and respect your father and husband and become a wise and obedient wife” he explains, striking her across the calves with a cane to teach her a lesson for her imperious tone in failing to pay him the proper respect.

Failing to use appropriately polite language with those around her, forgetting that she should now be deferent both to men and to those who exceed her in age, gets her into constant trouble. Nevertheless, a trip to the marketplace gains her a further understanding of the extremes in her society firstly when she misunderstands a rice cake seller’s patter and assumes he intended to gift her some of his produce as he might to a princess, and secondly when she bumps into a woman with a baby on her back and breaks the pots she was hoping to sell to pay for her husband’s medical care. Introduced to such desperate poverty, the undercover princess knows not what to do but later gifts her a jade pin hoping perhaps to at least cure the husband’s malady, only to wander into another dangerous situation when she is mistaken for a sex worker by a trio of drunken noblemen who pull her into a drinking establishment which is in fact a brothel. Naively drinking with the men she mocks them for their attempts to play on their names each boasting of their famous fathers and personal connections to men she knows to be elderly cranks and obsequious fools. Shocked to discover what goes in establishments like these she tries to make her escape but is almost assaulted by one of the men, Shim, who is later posited as an ideal match by her unsuspecting mother laying bare another patriarchal double standard as Shim plays the part of the gentleman in order to effect his advancement. Luckily, she is saved by Seon-do who happens to be passing but mistakes her for a boy because of the disguise she is currently wearing.

Selfish in her naivety, Suk-gyeong is warned that her impossible crush might end up harming Seon-do’s hopes of making it into the elite through success in the state exam while he, once made aware of the truth, immediately does the right thing by kindly rebuffing the princess’ inappropriate interest leaving her with a poetic love letter claiming he’s gone off to a temple for a spell of intensive study. Perhaps improbably it’s the love letter that eventually saves them, touching the king’s heart and convincing him to acquiesce to his sister’s wishes of escaping the gilded cage of nobility. Suk-gyeon’s pleas to renounce her royal title might also stand in for a desire to renounce womanhood in that it “stops us from doing anything we want. We are matched up with an unknown husband and we spend our youths in misery for our lives are tedious and pathetic”, reminding her brother that as a king but in truth as a man he cannot understand even while he reminds her that these are the “rules” endured by countless ancestors. The king is moved, he breaks with tradition and frees his sister yet he does so to allow her to become a wife even if he has also granted her the freedom to choose her husband and live in the outside world unconstrained by the strictures of nobility but nevertheless bound by oppressive patriarchal social codes. Nevertheless, it’s an unexpectedly progressive conclusion advocating for change and personal happiness over the primacy of duty and tradition.

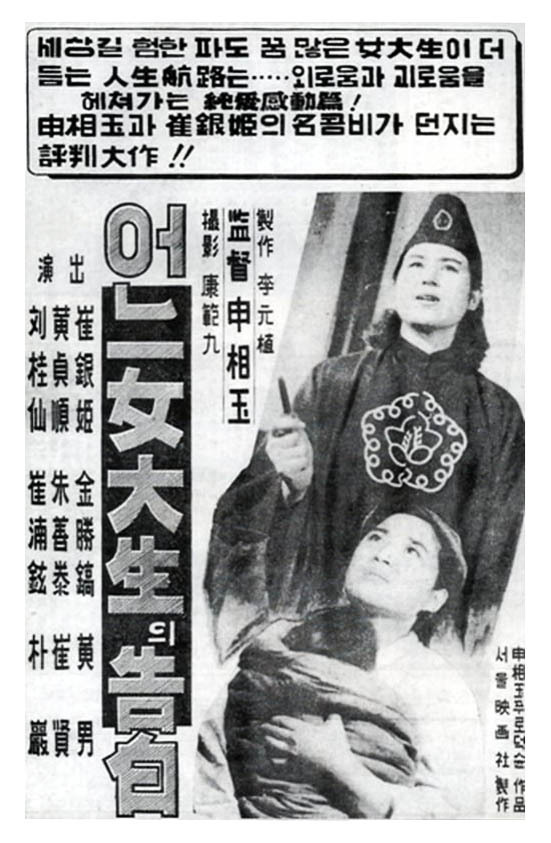

A Princess’ One-Sided Love streamed as part of the Korean Cultural Centre UK’s Korean Film Nights: Filming Against the Odds