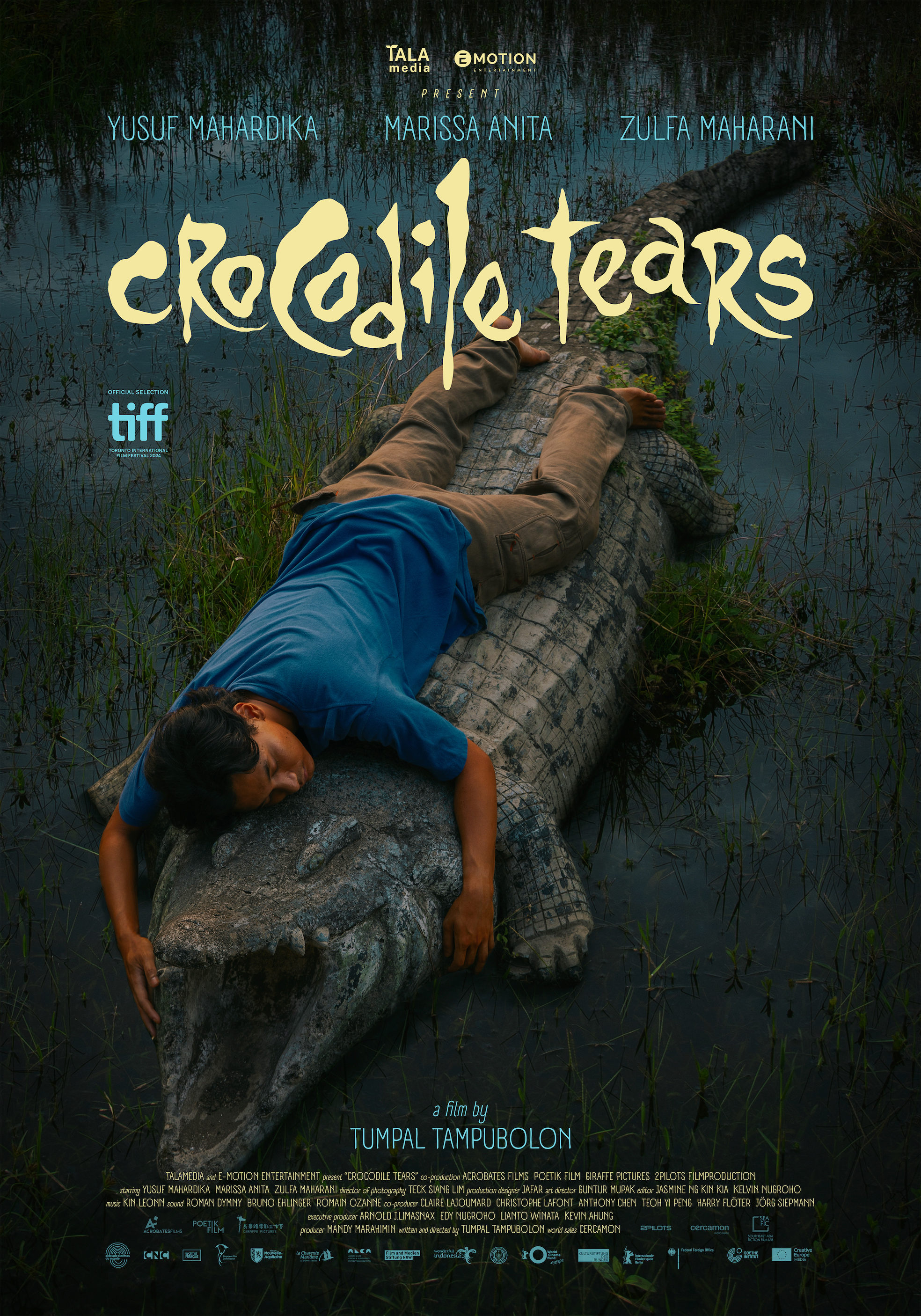

What happens when the baby wants to break out of the egg? The hero of Tumpal Tampubolon’s Crocodile Tears (Air Mata Buaya) isn’t a baby, he’s a 20-year-old man, but the crocodile zoo where he lives with his mother is also a kind of extended womb in which she keeps him constrained. The film’s title is apparently inspired by the fact that crocodiles protect their young by holding them in their jaws, the same jaws they use to snap at the live chickens Johan (Yusuf Mahardika) and his mother (Marissa Anita) throw over the fences.

Mama is evidently aware her little boy’s growing up. In the first shot of the film he’s furtively masturbating until he’s interrupted by her screaming for him outside. She scrubs his pants and seems to notice that they’re soiled, taking care to remind him that he should keep himself clean now he’s a grown man, but Johan doesn’t seem to understand telling her that he showers every day. Perhaps he’s smarting a little at her comments having overheard two women complaining about a bad smell while sitting next to him at a restaurant and wondering if he carries the stench of the crocodile park even when in the outside world. Later he takes to wearing some of the perfume he picked up for his mother’s birthday and had also given to his girlfriend Arumi (Zulfa Maharani).

Arumi is a direct threat to Mama who knows that another woman will inevitably replace her. She and Johan still sleep in the same bed. The irony is that her loneliness becomes that of Johan who is terrified of ending up all alone in the crocodile park prevented from having anything like a normal life by his mother’s possessive neediness. He loses his virginity to Arumi, a more worldly woman working in the local karaoke box and on the fringes of the sex trade, and she becomes pregnant though unsure whether or not Johan is the father. He realises he likely isn’t, but like his mother is so lonely that he doesn’t care only begging Arumi not to leave him because he can’t bear the idea of being on his own.

But despite the obvious conflict and rivalry between them, the past is essentially repeating with each woman oppressed by Indonesia’s oppressively conservative and patriarchal social norms. Mama had Johan at 19 and seemingly unmarried. Though she resented the baby in her womb, when he was born she gave all of herself to him and he became her entire world. There are rumours that Mama may have murdered her husband and fed him to the crocodiles though Johan says he never knew his father. He was told both that he had died before he was born and that his father is the zoo’s white crocodile whom his mother refers to as “Papa” and claims to have a special connection to “mentally”. Now Arumi looks her in the eye and says she will do for her child as she did for Johan, but she too has been railroaded into a marriage through lack of other options. Aside from the stigma attached to unwed motherhood, she is fired from the karaoke bar for shoving a customer who was harassing her with the boss apparently thinking it’s all part of her job and she should have known better than to upset a paying client.

The two women become almost like crocodiles in a cage snapping in defence of their territory as if knowing only one of them can stay. Plagued by strange visions, as is Arumi later, it seems the choice is really Johan’s of whether to bust out of his shell and symbolically break free of his mother’s womb or abandon the idea of starting his own family with Arumi to stay in there forever. Tumpal Tampubolon cracks up the sense of dread and eeriness beginning merely with discomfort in this quasi-incestuous relationship and heading into the realms of folk horror with its strange and surreal hallucinations that confront Johan with his Oedipal dilemma as he tries to crawl free only waiting to see if Mama’s jaw will finally snap.

Crocodile Tears screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival

Original trailer (English subtitles)