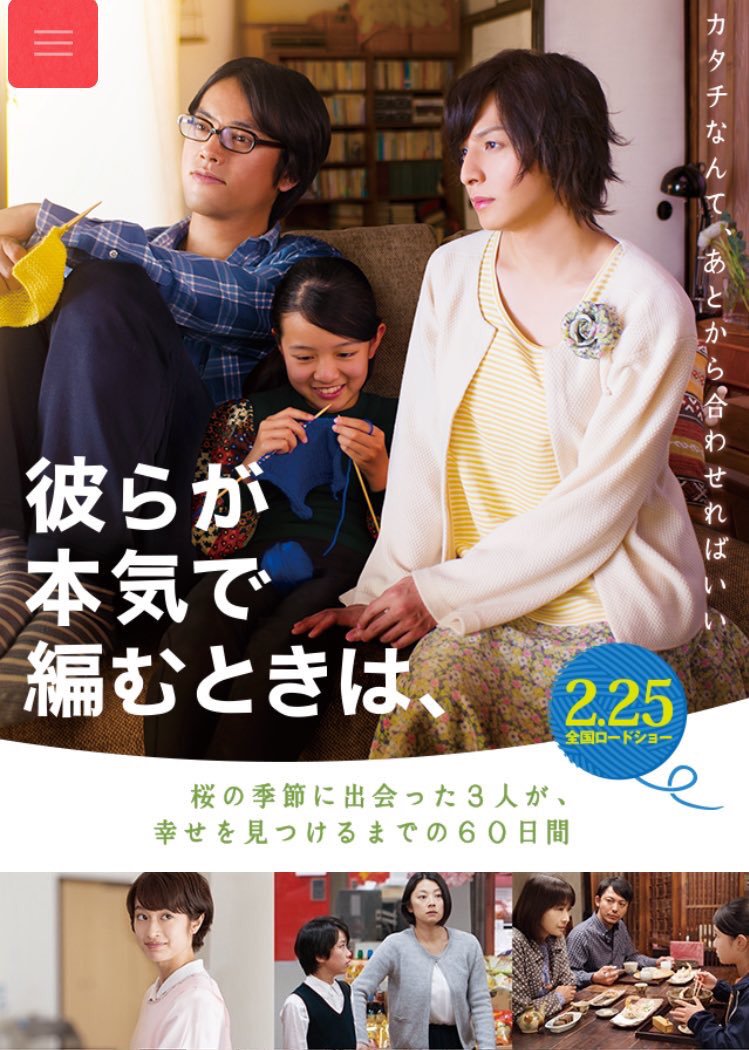

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

While studying in the US, director Naoko Ogigami encountered people from all walks of life but on her return to Japan was immediately struck by the invisibility of the LGBT community and particularly that of transgender people. Close-Knit (彼らが本気で編むときは, Karera ga Honki de Amu Toki wa) is her response to a still prevalent social conservatism which sometimes gives rise to fear, discrimination and prejudice. Moving away from the quirkier sides of her previous work, Ogigami nevertheless opts for a gentle, warm approach to this potentially heavy subject matter, preferring to focus on positivity rather than dwell on suffering.

11 year old Tomo (Rinka Kakihara) is home alone, again. Her mother rolls in late, dead drunk, and promptly flops down onto the futon next to Tomo’s still in her work clothes. A note left the next day explains that Tomo’s mother has quit her job and won’t be coming home for a while. This is not the first time she’s done this and the money she’s left is at least enough for a train ticket to visit uncle Makio (Kenta Kiritani). When Tomo slaps a collection of manga down in front of him at the bookstore where he works, Makio immediately realises what’s going on and is both infuriated with his sister and glad to take his niece in for a while until her mother comes to her senses.

There’s one potential problem. Makio now has a live-in girlfriend only she’s not quite what Tomo might be expecting. On meeting Rinko (Toma Ikuta), Tomo is indeed shocked but is soon won over by Rinko’s warm and loving nature. Rinko is a transgender woman who’s experienced her share of hardships in life but finally found fulfilment in her relationship with Makio though she has a lot of love to give and would dearly love a child of her own.

Used to being left to her own devices, Tomo is a tough and resourceful child but also one with a thick protective shell. Unused to being mothered, Tomo finds Rinko’s attempts to reach out to her difficult to bear, cycling back and forth through a pattern of affection and rejection. Where her mother left her only store bought onigiri (which she has come to hate) and cash, Rinko makes beautiful character bentos complete with octopus frankfurters and adorable panda faces. So touched is Tomo by this gesture that she can’t quite bring herself to eat it and eventually makes herself ill by finally deciding to enjoy it long after it’s past its best.

Nevertheless even if Tomo comes to bond with Rinko, there are still those who don’t approve of her existence. Tomo has a, well, not quite friend at school, Kai, who is somewhat ostracised by the other children who call him “gay” and write homophobic slurs on the classroom blackboard. Tomo, whilst sometimes hanging out with Kai who lives near to her outside of school, refuses to have anything to do with him in class lest she be rendered guilty by association. Growing closer to Rinko, Tomo also comes to an acceptance of and willingness to fight for Kai who has confided in her about his crush on another boy in their class. Kai’s mother (Eiko Koike), however, is not so understanding and so when she catches sight of Tomo in the supermarket with Rinko she offers to save her from the “weirdo” and later bans Kai from hanging out with his only friend in case he somehow catches “weirdness” from their atypical family setup. This attitude of hers eventually has potentially tragic consequences for her young son, left with nothing other than the prospect of maternal and later societal rejection eased only by Tomo’s firm insistence that there’s nothing wrong with him at all.

Unlike Kai’s mother, Rinko’s instantly understood and remained fully supportive of her child even whilst hauled into school for an explanation of why “Rintaro” has been skipping P.E.. Rinko’s mother not only goes out and buys lacy bras for her daughter, but even knits her a pair of fluffy pink breasts so she won’t feel so depressed about not developing in the same way as all the other girls. Tomo’s mother has a lot of problems of her own but many of these stem back to her own upbringing, unintentionally threatening to pass on some of these same qualities to her own daughter as she allows her to feel just as worthless and unloved as her mother did her. Yet, Ogigami’s camera remains resolutely unjudgemental in trying to understand each of these various facets of motherhood from the immense maternal love of Rinko as it finally finds an outlet in Tomo to the far less positive image of Kai’s mother who presumably thinks she’s doing the best for her son in trying to prevent him veering from the norm but only succeeds in making him feel his life is not worth living.

The title of the film, as grandly punned as it is, refers not just to the quickening family bonds among this idealised yet unusual family but also to Rinko’s favourite method of stress relief – knitting. Like the cooking she is often seen providing for the family, Rinko’s knitting is also largely about warmth in making something for a particular person which is tailor made to keep them warm in the cold, but it also works as a multilayered metaphor as she brings people together, binding them tightly with her own wamth and generosity of spirit. Rather than fighting back with angry words (or well aimed dish soap as a provoked Tomo eventually does), Rinko channels her frustrations into her knitting, using them to create something positive rather allowing negativity to overwhelm her. Ogigami’s film seems to want to do the same, arguing for tolerance, understanding, and acceptance as a pathway to a better world even if it’s clear the road is long and we’re not so far along it as we should be.

Close-Knit was screened as part of the Udine Far East Film Festival 2017

There’s also an interesting interview with director Naoko Ogigami and producer Kumi Kobata in the Nikkei Asian Review in which they discuss the casting of actor Toma Ikuta.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours.

Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours.