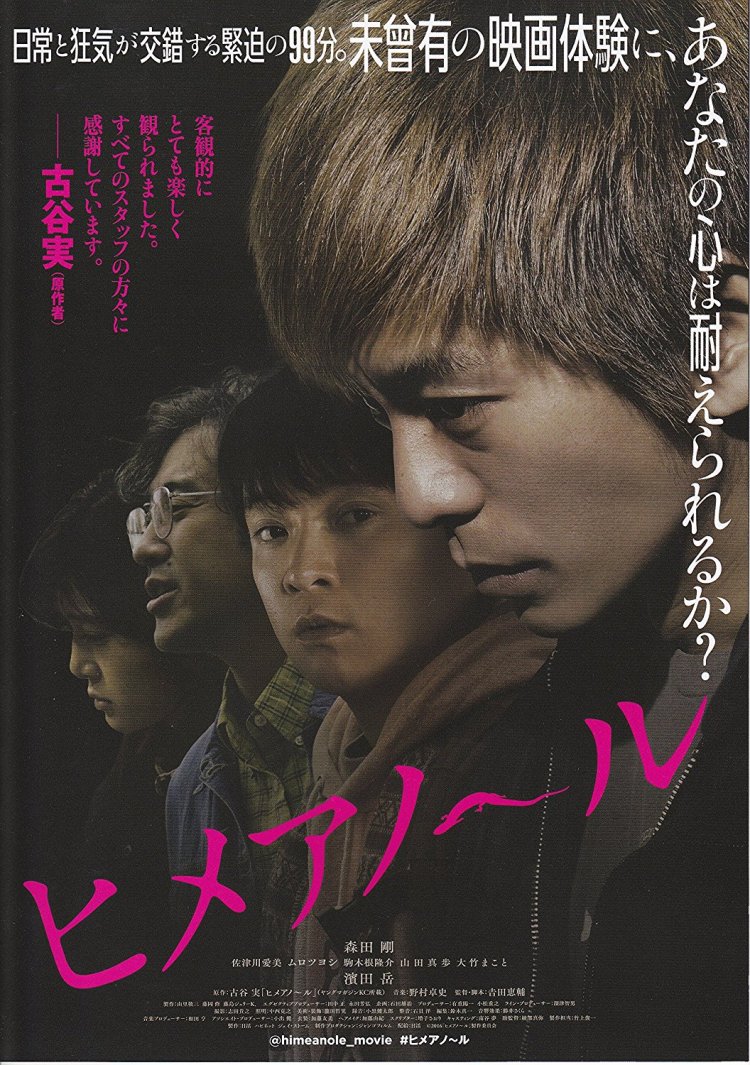

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Okada (Gaku Hamada) is a young man lost. He has a dead end construction job he doesn’t like and isn’t particularly good at, but treading cement all over the finished floors at least helps him bond with his mentor, Ando (Tsuyoshi Muro), who seems to view him as a friend even if constantly referring to him as “Okamura”. Okada takes the opportunity to explain his malaise to Ando – that he feels his life slipping away from him in its emptiness, going through the motions with no real hobbies or girlfriend to give his existence meaning. Ando does not really understand this, he says dissatisfaction is natural and the driving force of all life but, on the other hand, he is not particularly dissatisfied because he lives for love!

Ando has a crush on a girl at the local cafe, Yuka (Aimi Satsukawa), who actually hasn’t noticed him because she’s pre-occupied with the blond guy who got there before Ando and sits outside everyday just staring at her. Luckily or unluckily, the guy in question, Morita (Go Morita), is an old high school acquaintance of Okada’s and so Ando asks him to find out what’s going on with this scary looking guy and his angelic lady love.

So far, so Japanese indie rom-com, but when the title card flashes up about a third of the way in, we’re in very different territory. Suddenly the colour drains from the screen and Yoshida changes his aesthetic and shooting style almost entirely. Gone is the comforting, slightly washed out colour scheme and the static, middle-distance camera of the opening. Now we are the voyeur, held helpless behind Yoshida’s erratic shaky cam, hiding behind the bins as Morita goes about his bloody business. Morita’s world is dark yet realistic, he’s shot and positioned with the arch naturalism familiar to the Japanese indie and the violence he inflicts is not movie violence, it is shocking, sickening, and visceral.

Hime-anole does not shy away from the consequences of its actions. This is, in a way, its point. At one time or another everyone concludes the increasingly surreal events they become engulfed in must be all their fault because they all have at some point acted in a way they do not quite approve of. Guilt is another of the emotions that is hard to express, especially when it’s mixed with humiliation or fear, but left unaddressed it is these corrosive agonies which develop into deep psychoses. Morita, a violent sociopath, was once (or so it would seem) an ordinary young boy who liked video games and had few friends. Perhaps if he hadn’t been the victim of humiliating, sadistic treatment, or if someone had found the courage to stand up for him, none of this might be happening.

Then again, the world is a strange place filled with people who have trouble deciding where the lines are when it comes to appropriate behaviour. Poor Yuka seems to have become something of a nutter magnet, stalked by two guys at the same time and chatted up in the street by persistent suitors who only leave her alone when they realise she’s waiting for another man. Okada is the only man who’s treated her like a regular human being for a very long time so it’s no surprise that she begins to prefer him to his awkward friend. Ando is, it has to be said, odd. Convinced Yuka is the one for him yet completely uninterested in her feelings, he vows to persevere. Yet for all his talk of chainsaws, Ando is basically harmless (to others at least) and just another lonely guy who doesn’t know how to express himself in way in which he will be understood. Morita, by contrast, is instantly creepy and has no interest in connection, he only wants to take and possess in a kind of ongoing vengeance for truly horrific events in his childhood following which something inside him became very broken.

That Hime-anole ends with a Brazil-style fantasy only adds to its strangely melancholy air as it insists on sympathy for the devil even whilst showing each of his sadistic crimes for the ugly, bloody messes they really are. Maybe the reason everybody feels they’re to blame is that in some way they are yet everyone has done things they regret or aren’t proud of, wishing they’d done things differently or managed to find the courage to do what they thought was right rather than choosing to protect themselves or keep their head down when they could have saved someone else pain. Betrayals can be small things, but they fester – like those unspoken emotions which were making our guys so unhappy in the first place. There are no innocents in Hime-anole save perhaps for the ones pushed further than they could endure, but there are those finally facing up to their own flaws and attempting to do things differently now they know better. If that’s not progress, what is?

Original trailer (no subtitles)