“Your sense of duty is too strong! The world isn’t a pretty place,” barks an irate policeman, scolding a female officer with a tendency to take things, in his view at least, too far. Yukio Noda’s kidnap drama Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs (0課の女 赤い手錠, Zeroka no onna: Akai Tejo) is on the extreme end of pinky violence and soaked in the political concerns of the 1970s along with all their concurrent paranoia but nevertheless positions its fearless avenger as a lone arbiter of justice in an incredibly unjust world.

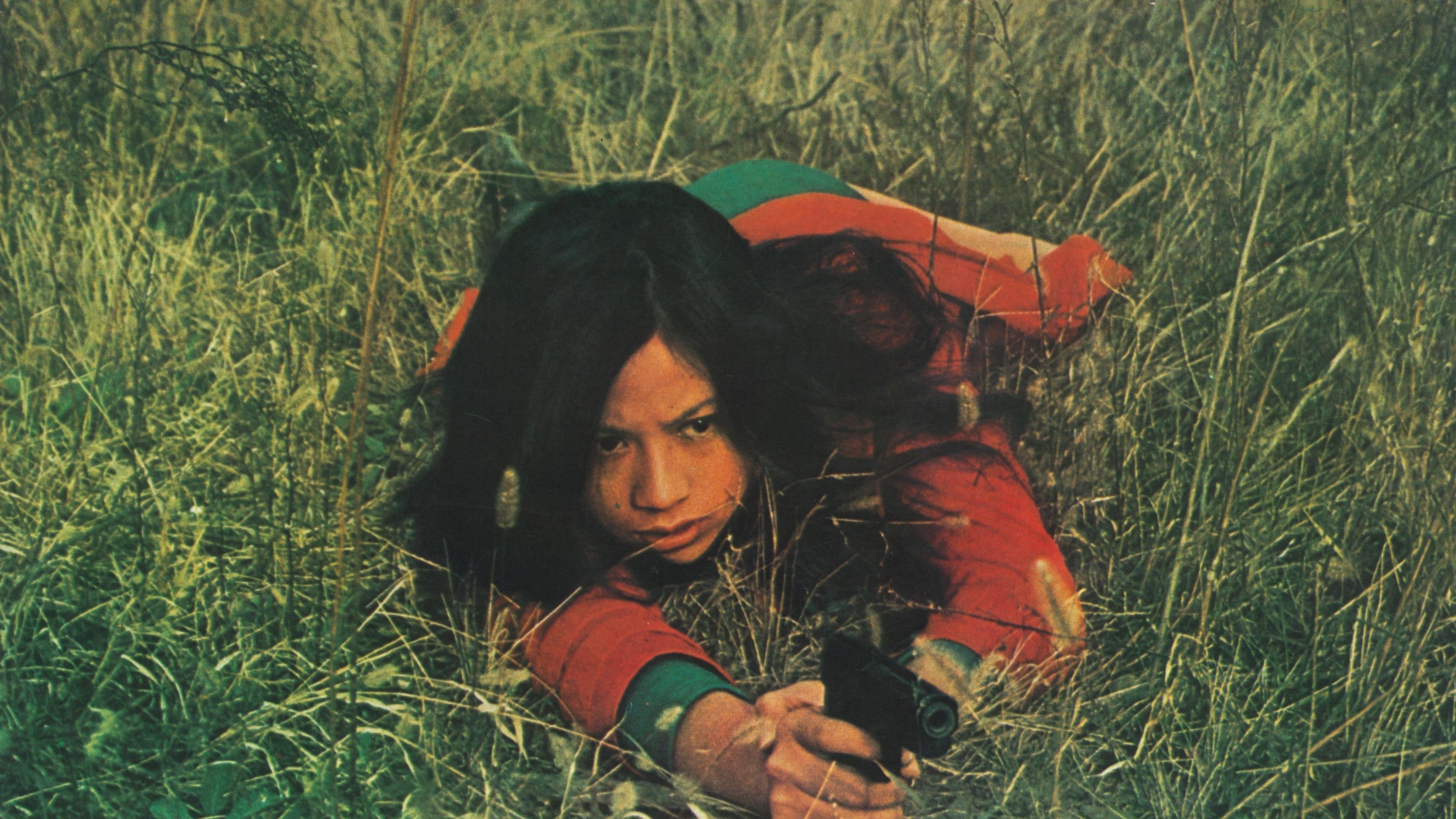

We know this from the start as we see Zero (Miki Sugimoto) almost date raped by an apparent serial killer who has his own torture suitcase and apparently killed her friend. Knowing that he is a diplomat and therefore has diplomatic immunity, she simply shoots him in the balls in the film’s extraordinary opening sequence. But even though it could be argued what she did was self-defence, Zero is kicked off the force and thrown into a woman’s prison for an indefinite period of detention to keep the lid on any possible scandal. Zero is only reprieved when the daughter of a politician is kidnapped by thugs and, wanting to keep things quiet, they need someone to rescue her and also wipe out all of the kidnappers to ensure no one ever finds out.

Kyoko (Hiromi Kishi), the politician’s daughter, claims that her father will do “anything” to ingratiate himself with the prime minister and has in fact already arranged her marriage to his son. Kyoko, however, already has a boyfriend who, inconveniently, is quite obviously a student protestor given his yellow construction hat and other paraphernalia. The pair are accosted while sitting in a car near an old American base, and as Kyoko is gang raped, firstly by the gang leader Nakahara (Eiji Go) who is wearing a hoodie with the words US Navy printed on the back, US planes fly over her as if she were being raped by America in an obvious metaphor for the legacy of the occupation.

Indeed, the flashbacks later experienced by Nakahara are of his mother whom he describes as a sex worker who worked at the base suggesting a very literal allusion to the corrupting influence of American servicemen. The gang operate out of a bar called “Manhattan” which is surrounded by other similar bars with Western names in a neon-lit area, while they constantly run across various signs written in English in fact peeing directly on a no peeing sign outside a largely disused residential area on the edge of the base where they later take hostage some kind of amateur dramatics / English-language class currently in the middle of a production of Romeo and Juliet.

Yet the big bad turns out to be essentially homegrown in the form of the corrupt lackey policeman Osaka, and the politician Nagumo (Tetsuro Tanba), who is more concerned with his political capital than his daughter’s safety keen that the police keep everything out of the papers otherwise the wedding will be called off and he’ll have a problem with the prime minister. Seeing a very pale Kyoko, her clothes torn, barely conscious having been drugged by the gang, he says he no longer cares to think of her as his daughter and perhaps it would be better if she simply passed away in an “accident”, instructing Osaka to care of loose ends like Zero too.

It’s very clear that women’s lives have little currency in this very patriarchal world, something Zero seems to know all too well even if at the beginning of the film she was content to work for the oppressive organisation of the police force though she later tears up her warrant card in disgust. The fact that division zero, operating like a secret police force on the behalf of an authoritarian government, exists at all is a clear indication that this is already a police state though one subverted by Zero who uses her red handcuffs to deliver ironic justice to all those who deserve it. Then again, unlike other pinky violence films there’s precious little solidarity that arises between herself and Kyoko whom she later describes as nothing more her mission objective seemingly caring little for her as a fellow human being. Noda cuts back between the Diet building and police HQ as if actively critiquing the latent authoritarianism of the early 70s society but even if Nagumo gets a kind of comeuppance it’s abundantly clear that nothing really will change and Zero stands alone wilfully freeing herself of the handcuffs of a controlling society.