Aspiring journalist Nami Tsuchiya (Eri Kanuma) works for a magazine called “The Woman,” but it soon becomes clear she’s their only female reporter and one of a handful of women in an office otherwise staffed by men. Her editor has her writing a series titled “Rape and its Consequences” in which she attempts to interview women who’ve experienced sexual assault in an attempt to root out the effect it’s had on their lives. At times Nami seems a little conflicted, puffing away on a cigarette with a pensive look on her face, but there’s no denying that she’s sold out other women for a chance to make it in a man’s world by exploiting a suffering she does not herself share.

Muraki (Takeo Chii), formerly a top magazine editor, reminds her that not everyone who reads her magazine is a woman, but there is something perverse about the idea of her article which is otherwise conceived from a perspective that seems very male. The female readership of this magazine would not need to be educated about the prevalence of rape nor its consequences. Nami’s article doesn’t seem to want to find success stories, but to revel in misery. She accosts one of the women she’s hoping to interview and tries to badger her into talking on the record. Yoshiko appears fed up and tells her that recounting what happened would be like being raped all over again, but still Nami doesn’t relent. She tries to guilt her into speaking by suggesting that her testimony would stop other women being assaulted, which is backwards logic seeing as it isn’t the women who are responsible and even if she were advancing a victim blaming narrative that it’s on women to protect themselves, Yoshiko had not done anything that could be seen to be “wrong” nor is there any way she could have prevented what happened to her.

Through her articles, Nami has become complicit in this culture and is effectively an agent of rape herself in her desire to tear into the lives these women have tried to build for themselves and extract even more salacious detail. She describes Yoshiko as “happily married,” but she’s living in a rundown house on the margins of the city. It seems her husband maybe ill and therefore unable to work. Yoshiko may have married him out of a lack of other options and it’s not clear if her husband knows about her past or how he would react if he learned of it now. The fact that Nami’s attempt to interview others about Yoshiko fails bears out the social stigma that can surround those who’ve experienced sexual assault and suggests that Yoshiko has now become an outcast. The photos that they publish only black out Yoshiko’s eyes making it easy for those in her community to identify her which could certainly make her life much more difficult and lead to a loss of employment or social further exclusion.

It’s clear that Nami hasn’t really thought any of this through and is only focussed on impressing her male editors to be given better assignments. This may in part be what she means when she says that she’s been assaulted in her office by the people she works with on gaining more of an insight into the consequences of her writing. Though he threatens to rape her himself, Muraki seems to be a representative of a more compassionate masculinity but at the same time has been emasculated, rendered impotent after his own wife was raped by an intruder and then left him because he couldn’t satisfy her sexually. He connects Nami with a mentally disturbed nurse who was assaulted by a doctor with an autopsy fetish, though the incident was covered up by the hospital. None of these men, except Muraki, is held responsible for their actions. Nami, however, becomes all of these women, envisioning herself abandoned at the scene half-naked and clothes torn, discarded on the rubbish tip of the modern society. At the beginning of the film, a woman smashes the lens of the camera as a man moves towards her, as if she meant to rebuke us for watching, while even Nami finds herself becoming dangerously aroused by watching other women being assaulted or listening to their stories before she too cracks and begins to see herself as nothing more than an anonymous object at the mercy of male society.

Angel Guts: Nami is available as part of The Angel Guts Collection released on blu-ray 23rd February courtesy of Third Window Films.

Each year the Nippon Connection film festival runs a retrospective programme alongside its collection of recent indie and mainstream hits. The subject for this year’s strand is Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno. Heading into the 1970s, Japanese cinema was in crisis mode as TV poached cinema audiences who largely stayed away from the successful genres of the 1960s including the previously popular youth, action, and yakuza movies which had been entertaining them for close to 20 years. Daiei, one of the larger studios known for glossy, big budget prestige fare alongside some lower budget genre offerings went bust in 1971, Shochiku kept up its steady stream of melodramas, but Nikkatsu found another solution. Taking inspiration from the “pink film” – a brand of soft core, mainstream pornography shown in specialised cinemas and made to exacting production standards, they created “Roman Porno” which made sex its selling point, but put big studio resources behind it, bringing in better actors and innovative directors to lend an air of legitimacy to its purely populist ethos.

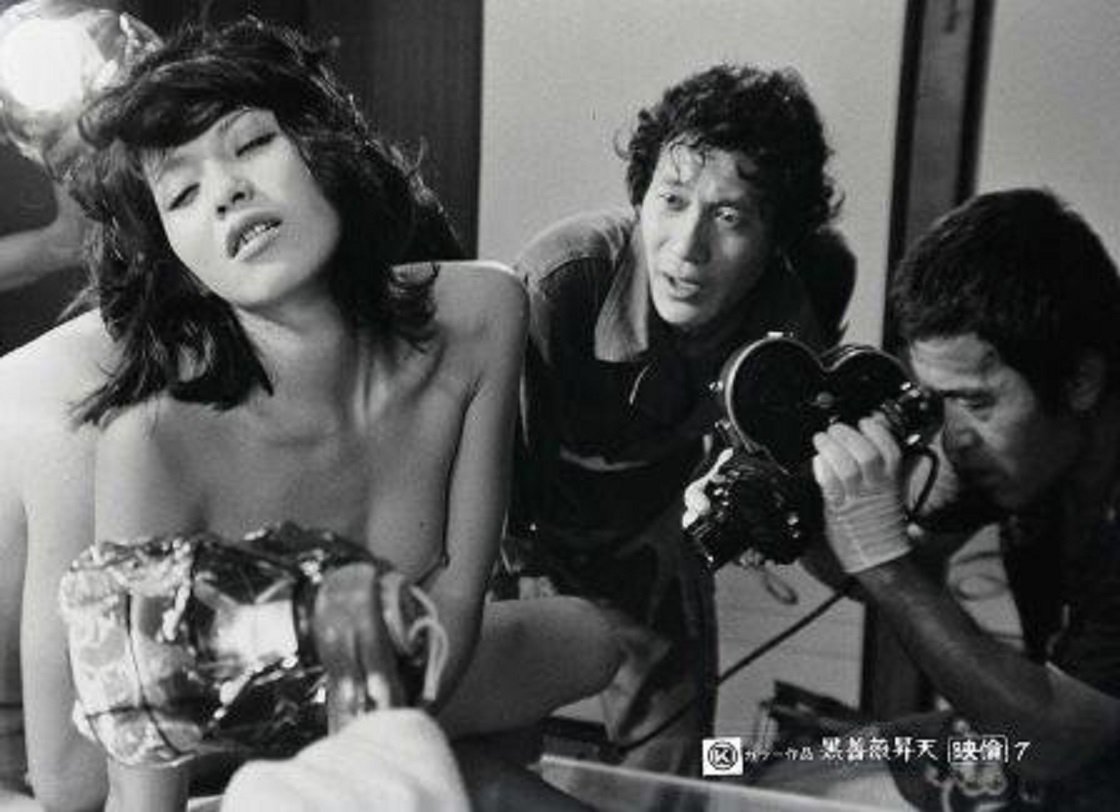

Each year the Nippon Connection film festival runs a retrospective programme alongside its collection of recent indie and mainstream hits. The subject for this year’s strand is Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno. Heading into the 1970s, Japanese cinema was in crisis mode as TV poached cinema audiences who largely stayed away from the successful genres of the 1960s including the previously popular youth, action, and yakuza movies which had been entertaining them for close to 20 years. Daiei, one of the larger studios known for glossy, big budget prestige fare alongside some lower budget genre offerings went bust in 1971, Shochiku kept up its steady stream of melodramas, but Nikkatsu found another solution. Taking inspiration from the “pink film” – a brand of soft core, mainstream pornography shown in specialised cinemas and made to exacting production standards, they created “Roman Porno” which made sex its selling point, but put big studio resources behind it, bringing in better actors and innovative directors to lend an air of legitimacy to its purely populist ethos. Ecstacy of the Black Rose is a more comedic effort than most of Kumashiro’s output and takes an ironic look at the genre as a put upon director gets fed up when his leading actress falls pregnant and becomes obsessed with finding a woman whose moans he overheard at the dentist’s.

Ecstacy of the Black Rose is a more comedic effort than most of Kumashiro’s output and takes an ironic look at the genre as a put upon director gets fed up when his leading actress falls pregnant and becomes obsessed with finding a woman whose moans he overheard at the dentist’s. Following Desire received a Kinema Junpo award for best screenplay as well as the best actress prize for Hiroko Isayama who plays a stripper intent on taking down her rival for the top spot!

Following Desire received a Kinema Junpo award for best screenplay as well as the best actress prize for Hiroko Isayama who plays a stripper intent on taking down her rival for the top spot! Kumashiro’s Tamanoi Street of Joy takes place on the last day of legal prostitution in 1958 and follows the girls as they mark the occasion in their own particular ways.

Kumashiro’s Tamanoi Street of Joy takes place on the last day of legal prostitution in 1958 and follows the girls as they mark the occasion in their own particular ways. Further proving Kumashiro’s critical stature, Twisted Path of Love was among Kinema Junpo’s 1999 list of the greatest Japanese films of the 20th century. The story of a young man who returns to his hometown but attempts to shed his identity, burning a hole in the conventional village life through sex and violence, Twisted Path of Love also displays Kumashiro’s interesting use of common censorship techniques for artistic effect.

Further proving Kumashiro’s critical stature, Twisted Path of Love was among Kinema Junpo’s 1999 list of the greatest Japanese films of the 20th century. The story of a young man who returns to his hometown but attempts to shed his identity, burning a hole in the conventional village life through sex and violence, Twisted Path of Love also displays Kumashiro’s interesting use of common censorship techniques for artistic effect. Often regarded as Kumashiro’s masterpiece, The Woman with the Red Hair picked up a Kinema Junpo best actress award for Junko Miyashita, as well as ranking fourth in their annual best of the year list. The story centres on construction worker Kozo who, along with friend Takao, rapes his boss’ daughter who subsequently becomes pregnant. While she asks Takao to marry her, Kozo embarks on an affair with the mysterious red-haired woman.

Often regarded as Kumashiro’s masterpiece, The Woman with the Red Hair picked up a Kinema Junpo best actress award for Junko Miyashita, as well as ranking fourth in their annual best of the year list. The story centres on construction worker Kozo who, along with friend Takao, rapes his boss’ daughter who subsequently becomes pregnant. While she asks Takao to marry her, Kozo embarks on an affair with the mysterious red-haired woman. Another of Kumashiro’s most well-regarded Roman Porno, The World of the Geisha takes place in a geisha house in 1918 and examines the various tensions which exist between the women themselves and their customers who have come to the house to escape external political concerns. The film again demonstrates Kumashiro’s tendency to ironic commentary as he tampers with intertitles to make a point about censorship.

Another of Kumashiro’s most well-regarded Roman Porno, The World of the Geisha takes place in a geisha house in 1918 and examines the various tensions which exist between the women themselves and their customers who have come to the house to escape external political concerns. The film again demonstrates Kumashiro’s tendency to ironic commentary as he tampers with intertitles to make a point about censorship. Night of the Felines provides the inspiration for Kazuya Shirashi’s reboot Dawn of the Felines and follows the comical adventures of three prostitutes.

Night of the Felines provides the inspiration for Kazuya Shirashi’s reboot Dawn of the Felines and follows the comical adventures of three prostitutes. Stroller in the Attic is among the best known in the Roman Porno canon and adapts an Edogawa Rampo short story about a ’20s boarding house filled with eccentric guests.

Stroller in the Attic is among the best known in the Roman Porno canon and adapts an Edogawa Rampo short story about a ’20s boarding house filled with eccentric guests. Inspired by the same real life case as In the Realm of the Senses, Noburu Tanaka’s Sada and Kichi takes a more lurid look at the strange case of Abe Sada who strangled her lover after a brief affair and then cut off his genitals to wear as a kind of talisman.

Inspired by the same real life case as In the Realm of the Senses, Noburu Tanaka’s Sada and Kichi takes a more lurid look at the strange case of Abe Sada who strangled her lover after a brief affair and then cut off his genitals to wear as a kind of talisman.