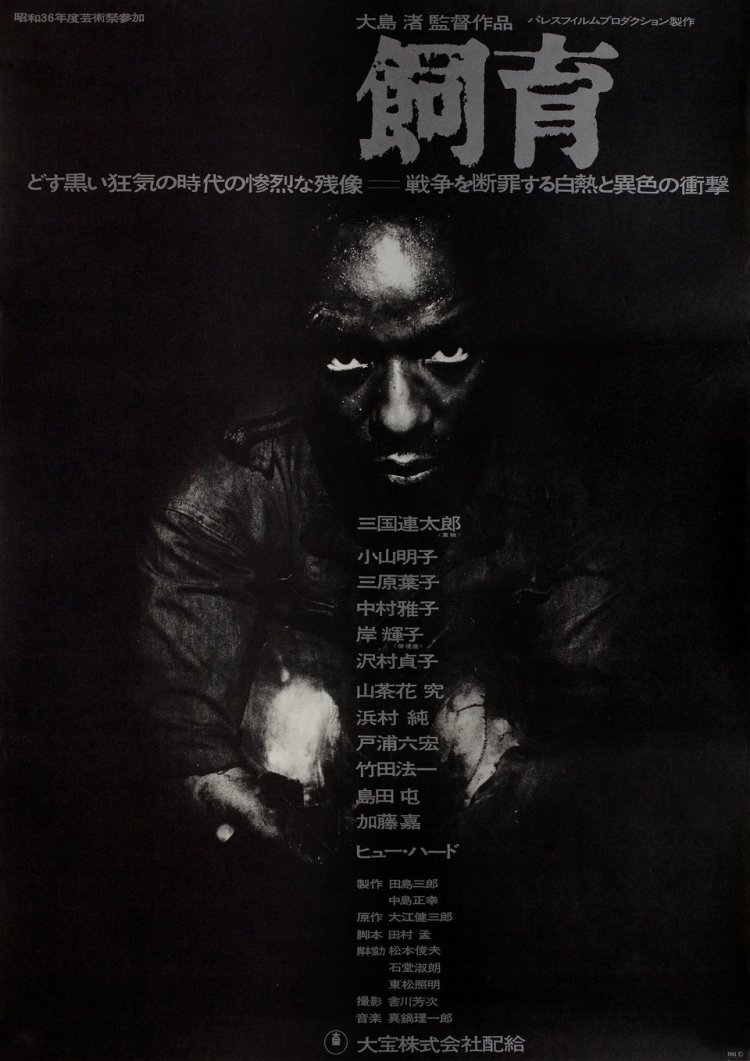

1960 was a turbulent year for many, not least among them Nagisa Oshima who dramatically broke his contract with Shochiku after the studio withdrew Night and Fog in Japan on grounds of sensitivity after the leader of Japan’s Socialist Party was murdered by a right-wing assassin live on TV. 1961’s The Catch (飼育, Shiiku), an adaptation of a novel by Kenzaburo Oe, was Oshima’s first post-studio picture and as uncompromising as anything else he’d worked on up to that point. Unlike many other filmmakers of the post-war generation who had been keen to use the corruption of the war as an excuse for a failure of humanity they now thought could be repaired, Oshima suggests that the rot was there long before and all the war did was give it justification.

1960 was a turbulent year for many, not least among them Nagisa Oshima who dramatically broke his contract with Shochiku after the studio withdrew Night and Fog in Japan on grounds of sensitivity after the leader of Japan’s Socialist Party was murdered by a right-wing assassin live on TV. 1961’s The Catch (飼育, Shiiku), an adaptation of a novel by Kenzaburo Oe, was Oshima’s first post-studio picture and as uncompromising as anything else he’d worked on up to that point. Unlike many other filmmakers of the post-war generation who had been keen to use the corruption of the war as an excuse for a failure of humanity they now thought could be repaired, Oshima suggests that the rot was there long before and all the war did was give it justification.

In the summer of 1945, a small village captures a black American airman (Hugh Hurd) shot down over a nearby forest. They are originally quite jubilant about their act of heroism, believing that they will eventually be rewarded by the authorities, but are then irritated by their new responsibility. They are already low on food, and now they’ll have to feed this full grown man or risk being branded as amoral war criminals. Predictably, nobody wants to be saddled with looking after him until the authorities arrive with further instructions or knows what to do now, so in time-honoured fashion they tie him up in a shed and hope for the best. Only latterly when one of the children points it out do they realise that they should probably remove the bear trap attached to the airman’s foot which may already be infected seeing as he seems to be in a considerable amount of pain and is running a high fever.

It goes without saying that villagers are extremely racist, using quite pointed racial slurs and dehumanising language to describe their captive, even when others stop to remind them that he is after all human too even if he’s an enemy. Just as their sons and husbands are overseas fighting, and dying, bravely for the emperor so was this man valiantly risking his life for his country. Shouldn’t he be accorded some respect just for that? Wouldn’t they want that for their sons too?

Sadly thoughts are thin on the ground, as is food. Jiro (Toshiro Ishido), a young man shortly to enlist, wants a bag of rice off his dad to take into town to buy a woman, but his dad doesn’t have any because he’s already in debt to the immensely corrupt village chief (Rentaro Mikuni). Jiro eventually satisfies himself with a sexually liberated high school girl evacuated from the city and thereafter disappears – the first of many negative events to be randomly blamed on the captive airman. Meanwhile the village chief is responsible for a series of problems because of his out of control need for sexual dominance which sees him apparently abusing his daughter-in-law (Masako Nakamura) and attempting to assault a young widow (Akiko Koyama) with two children evacuated from the city and otherwise undefended in the village.

The rot here is feudalism, the idea that gives free rein to the village chief to misuse his position for his own satisfaction – extracting sexual favours from the women and controlling the men economically. Because he’s the village chief no one really questions his authority or his orders, so when he says all the problems are new and caused by the “black monster” they’ve brought into the village then everyone believes it to be true. The airman, who cannot be responsible for any of these crimes because he is still recovering and locked up in the shed, becomes a scapegoat for every bad thing that has ever happened in the village. More than an embodiment of the war, he is a symbol of all the external pressures that the village would like to pretend are the reasons it has turned in on itself.

Yet the airman is only one kind, the deepest kind, of other. The village hasn’t quite even integrated its evacuees who also constitute a secondary community. The young woman’s two starving children are repeatedly caught with their fingers in other people’s rice jars and receive little sympathy from the villagers, but their crimes only expose the fact that the man who has sheltered them, and also owns the shed where the airman is kept, has been keeping quiet about people thieving his potatoes. He knows it’s not the widow because there are simply too many taken to feed a small family of three, which means that there are probably several “thieves” among the villagers, content to betray their neighbours in thinking that the wealthy farmer won’t miss a measly few root vegetables.

Predictably, rather than deal with the problem, everyone obsesses over the idea that the corruption is born only of the airman and if they could just eliminate him everything would go back to “normal” – i.e. the feudal past in which everyone does what the village chief says and lives in superficial harmony without complaining about their reduced status as lowly peasants forced to live in penury by an unfair and essentially corrupt system. To cure the discord between them, they decide that the airman must be killed, no longer caring about the censure they may face from the authorities. Only two young boys stick up for him, remaining sane amid the madness all around them in insisting that the airman is a person too, is unrelated to the village drama, and deserves his dignity and respect. Sadly, however, the madness has already taken hold.

On learning that the war is over, the villagers refuse to reflect on their behaviour and seek only to bury the past, superficially smoothing over their barbarity with convenient justification. They receive the news that the American authorities do not trust the Japanese with surprise and hurt, despite the fact they are living proof of the reasons why they would be foolish to do so. We gave him white rice while we ate potatoes, he had goats milk, they say, what more could he have wanted? The answer is self evident, but it’s already been forgotten. The villagers start blaming each other, and eventually settle on another scapegoat – a deserter, as if another death could tie all of this into a neat bundle to be burned away on a funeral pyre as if it never existed at all. The evacuees are invited to leave, and the villagers start thinking about the harvest festival, as if the evil has been excised and everything is returning to the way it’s supposed to be, but this “peace” is brokered on the back of secrecy and an abnegation of responsibility. A grim exposé of man’s essential cruelty and selfishness, The Catch rejects the tenets of post-war humanism to suggest that the corruption of feudalism has not and may never be eliminated at least as long as a nation remains content to bury its past along with its shame.

Short clip (English subtitles)