The obvious irony in the title of Kim Dae-woo’s erotic thriller Hidden Face (히든페이스), is that it refers both to the heroine, Su-yeon (Cho Yeo-jeong), who conceals herself within a secret bunker in her home to spy on her indifferent social climber boyfriend Sung-jin (Song Seung-heon), and to the sides of themselves that people choose not to reveal to others. As Su-yeon’s mother (Cha Mi-kyung) says, it’s what people see that matters, but the hidden corridors of Su-yeon’s home symbolise the ways in which she has imprisoned her true self or at least has locked a part of herself away from prying eyes while continuing to pry into the secret lives of others.

It’s in this forbidden space, apparently added to the house by the previous father’s owner who was a member of notorious Japanese Unit 731 during the war and feared exposure, that Su-yeon first kissed fellow student Mi-ju (Park Ji-hyun) with whom she’s been in a long-term, but apparently secret, relationship. While Mi-ju is patiently renovating the house she thinks they’ve bought together, Su-yeon has decided that she wants a “real life that people recognise”, which she evidently doesn’t believe a same-sex relationship can be. The forbidden space of “cold room” is then where she’s locked her queerness, and a manifestation of her fears of the consequences of exposure. The problem is that she doesn’t even like Sung-jin and the points of attraction he seems to hold for her are that he doesn’t like her either and is otherwise easy to manipulate because of the vast class difference between them.

Part of the reason that Sung-jin keeps Su-yeon at arms’ length is that he resents the power that she holds over him. He resents both her and himself in knowing that he’s really only with her for material reasons, while simultaneously aware that his current success has nothing to do with his own talent and everything to do with Su-yeon’s privilege. Su-yeon’s mother congratulates him on working hard to build an image of himself, while otherwise needling him about his working-class background in which his mother ran a small restaurant and really knows nothing of this elite world of classical music, mansions, and honeymoons to resorts that charge some people’s annual wage for a single night’s stay. But the facade can’t really cover up Sung-jin’s insecurity and the fear that he couldn’t make it on his own though he so desperately wants to be a part of this world and to feel himself worthy of it. He feels emasculated and humiliated in assuming that other people can see that he’s just a puppet while Su-yeon, her mother, and their advisor discuss policy decisions he’s technically responsible for out in the open, he assumes to deliberately embarrass him and keep him under control.

Yet the truth is that these kinds of hierarchal power structures of class and gender are less relevant when it comes to desire than otherwise might be assumed. Su-yeon refers to Mi-ju as her slave or underling and adopts a dominant role in the relationship yet eventually has the tables turned on her when Mi-ju decides to rebel. The power dynamic of desire is a push and pull between the desire and the desired mediated by the depth of yearning. It may seem to Su-yeon that she is in control, but equally Mi-ju derives power from her willing submission and can overturn the dynamic at any time she chooses upending Su-yeon’s delusion that Mi-ju is a mere plaything, or “tool”, she can take out and put away at will.

Nevertheless, the question is whether anyone could be content with this shadow life or if Su-yeon, vain, psychopathic, and probably incapable of understanding other people’s feelings, is content to imprison herself within the hidden corridors of her home which come to stand in for the need to conform to the heteronormative, patriarchal, class-based social codes other people see as “real” and “normal”. Sung-jin is apparently all too willing, considering just leaving Su-yeon trapped behind their walls to continue enjoying this life of privilege with a little more freedom without considering that without Su-yeon he has no entitlement to it as her mother later suggests after becoming worried on realising that Su-yeon hasn’t used her credit in days which is extremely uncharacteristic behaviour.

Sung-jin would trade his pride as a man, his sense of self-worth, and even betray his moral code to appear wealthy and successful and deny his working-class origins. Su-yeon would also, it seems, rather be in a conventional marriage to a man for whom she feels only contempt and resents for not liking her, than live an authentic life as a lesbian and face her internalised homophobia along with that of the wider society. Thus she confines Mi-ju to a forbidden space of her mind in an attempt to have her cake and eat it too, while Mi-ju seemingly fulfils herself in wilfully becoming a prisoner of love, even if it may only be in Su-yeon’s fantasy. Perhaps they get what they wanted all along, affirming the primacy of privilege, but only at the cost of their authentic selves and trapped inside the prison of their own self-loathing.

Hidden Face is released Digitally in the US on September 16 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

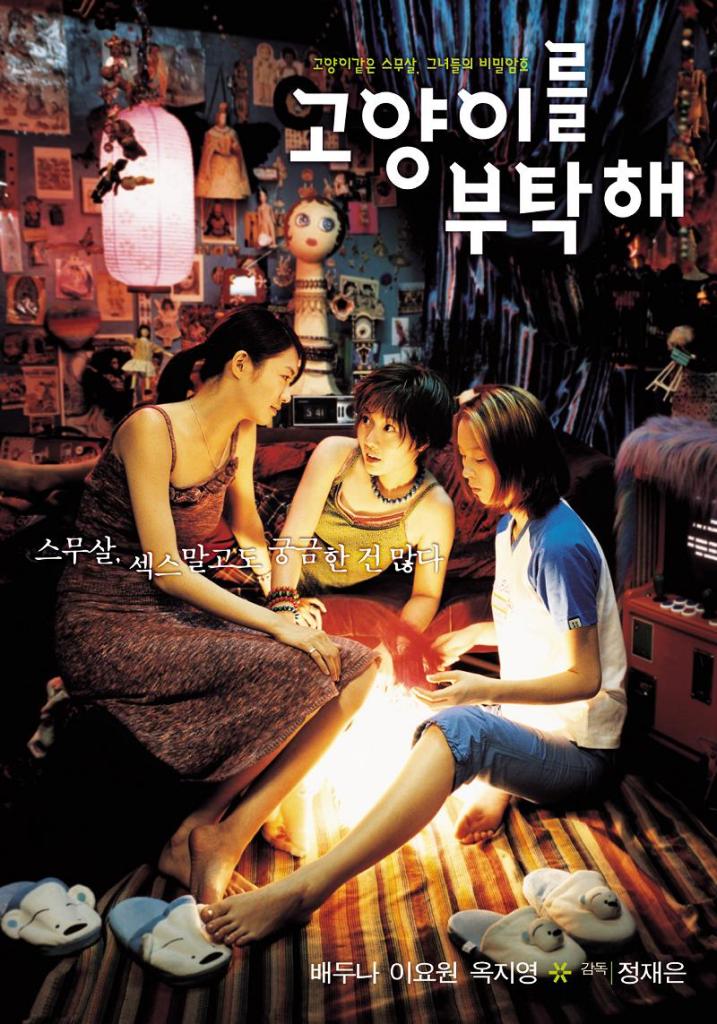

The time after high school is often destabilising as even once close groups of friends find themselves being pulled in all kinds of different directions. So it is for the group of five young women at the centre of Jeong Jae-eun’s debut feature, Take Care of My Cat (고양이를 부탁해, Goyangileul Butaghae). All at or around 20, the age of majority in Korea, the girls were a tightly banded unit during high school but have all sought different paths on leaving. Lynchpin Tae-hee (Bae Doo-na) is responsible for trying to keep the gang together through organising regular meet ups but it’s getting harder to get everyone in the same place and minor differences which hardly mattered during school grow ever wider as adulthood sets in.

The time after high school is often destabilising as even once close groups of friends find themselves being pulled in all kinds of different directions. So it is for the group of five young women at the centre of Jeong Jae-eun’s debut feature, Take Care of My Cat (고양이를 부탁해, Goyangileul Butaghae). All at or around 20, the age of majority in Korea, the girls were a tightly banded unit during high school but have all sought different paths on leaving. Lynchpin Tae-hee (Bae Doo-na) is responsible for trying to keep the gang together through organising regular meet ups but it’s getting harder to get everyone in the same place and minor differences which hardly mattered during school grow ever wider as adulthood sets in.