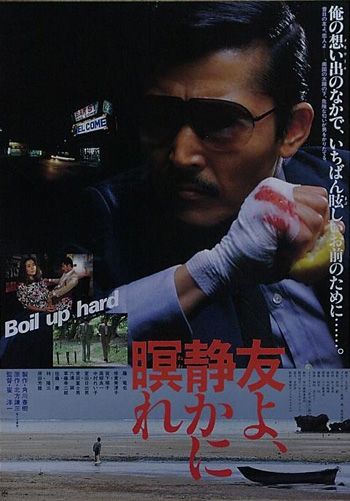

A beaten-down beat cop’s existential crisis progressively deepens after he throws himself into financial ruin to buy a computer in Yoichi Sai’s debut The Mosquito on the Tenth Floor (十階のモスキート, Jikkai no Mosquito). Like Pool Without Water, star Yuya Uchida conceived and co-scripted the film as a vehicle for himself and was apparently inspired by the sight of some blood, his own, on a wall where he’d squashed a mosquito though he also claimed the the 10 in the title is intended to reference the 10 commandments in addition to simply where the unnamed protagonist lives.

The fact that he lives on the 10th and top floor in a building with no lift is symbolic of his dismal circumstances. On the one hand he can rise no higher but on the other is stuck with an inconvenient living situation precisely because of his inability to rise socially. As it transpires the hero, a policeman, joined the force right out of high school with aspirations of rising to the rank of captain but has spent the entirety of his 20-year career manning a police box. He’s repeatedly failed the exam for promotion to lieutenant and realistically speaking is now simply too old to make much further progress. A man of few words, he listens as the other officers who took the exam with him outline the hierarchal structure of the police force while meditating that as a man on the wrong side of 40 his possibilities have decreased and it’s more than likely he’ll be stuck in the police box until he retires.

His boss later says as much, sympathising with him but also pointing out that a policeman is also a public servant with a role to serve within the community. He is supposed to make people feel safe and contribute to the progress towards a crime-free society, but it’s clear that his life has spiralled out of control precisely because he cannot ally his career goals with the kind of life he wished to lead. His wife divorced him two years ago seemingly because she wanted a greater degree of material comfort and became resentful that he failed to progress in his career and could not move on from the low-salaried position of an ordinary street cop. She now makes a living selling golf club memberships, looking ahead to the oncoming Bubble-era and a society of affluent salarymen which is very much what her new boyfriend seems to be. Meanwhile, she lives in a very nice townhouse with their teenage daughter and constantly hassles the policeman for falling behind with his child support and alimony payments. He’s also racked up a healthy tab at a karaoke bar where he regularly hangs out and has a serious gambling problem with betting on boat races seemingly his only other form of social outlet.

As his daughter and others keep reminding him, the world is changing and his decision to buy a computer after unwisely taking out a payday loan is in part a symbol of his desire to progress into the modern society even if, somewhat ironically, others chastise him for spending what is then a huge amount of money on something they think of a child’s toy. Otherwise an upstanding policeman who irritatedly deflects a colleague’s joke about bribing someone to pass the exam, the policeman finds himself taking out one payday loan to pay another with loansharks constantly ringing him at the police box to remind him he’s behind on his payments. To overcome his sense of powerlessness, he begins by abusing his authority in catching a punk woman shoplifting and arresting her but then taking her back to his flat to play computer bowling and take advantage of her sexually. He later does something similar with a bar hostess, Keiko (Reiko Nakamura), who took him home when he was drunk. Though the encounter begins as rape, Keiko soon gives in and even comes back for more claiming that she’d never done it with a policeman before and it exceeded her expectations which is in many ways reflective social attitudes at the time. Emboldened, he invites danger by raping a female traffic cop, tearing her clothes as she fights back, screams, and cries though she presumably does not report him given the professional and social consequences that may adversely affect her life and career if she chose to.

His ex-wife Toshie (Kazuko Yoshiyuki) says she’s not even sure if he’s human anymore, and his failed attempt to rape her after his boss reminds him that he advised against getting a divorce in the first place because it would negatively affect his chance of promotion may be a perverse way to prove he is though it obviously backfires. Having failed in every area of his life and with no prospect of ever getting back on track or starting again, he begins to go quietly insane typing rude words into his computer while the constant calls from loansharks take on a mosquito-like buzzing as does his own final wail of despair and powerlessness as he’s brought down by same authority he once served. His aloneness and confusion are palpable when he ventures into the city and discovers his teenage daughter Rie (Kyoko Koizumi) dancing in Harajuku staring at her intently but then walking away having invaded this space reserved for the young. “Police yourself!” one of the Rockabilly guys ironically instructs him on noticing that he’s dropped his ice cream cone, explaining that the police might shut them down if they’re discovered to be using the space irresponsibly by littering. Rie and her friends tell him to get a life, explaining that the world is changing while tapping him for cash he doesn’t have but is too embarrassed to refuse, laying bare the extent to which he and those like him have been left behind by the economic miracle, buzzing around maddeningly in mid-air with safe nowhere safe to land.

Original trailer (no subtitles)