Actress of the moment Sakura Ando steps into the ring, literally, for this tale of plucky underdog beating the odds in unexpected ways. It would be wrong to call 100 Yen Love (百円の恋, Hyaku Yen no Koi) a “boxing movie”, it’s more than half way through the film before the protagonist decides to embark on the surprising career herself and though there are the training sequences and match based set pieces they aren’t the focus of the film. Rather, the plucky underdog comes to the fore as we watch the virtual hikkikomori slacker Ichiko eventually become a force to be reckoned with both in the ring and out.

Actress of the moment Sakura Ando steps into the ring, literally, for this tale of plucky underdog beating the odds in unexpected ways. It would be wrong to call 100 Yen Love (百円の恋, Hyaku Yen no Koi) a “boxing movie”, it’s more than half way through the film before the protagonist decides to embark on the surprising career herself and though there are the training sequences and match based set pieces they aren’t the focus of the film. Rather, the plucky underdog comes to the fore as we watch the virtual hikkikomori slacker Ichiko eventually become a force to be reckoned with both in the ring and out.

Ichiko Saito is a 32-year-old woman with no job who still lives at home in her parents’ bento store where she also refuses to help out. With unkempt hair, slobbish pyjamas and a bad attitude, she stays in all day playing video games with her nephew other than running out to the 100 yen store late at night for more cheap and nasty snacks. Her sister has recently moved home after a divorce and to put it plainly, the two do not get on. Finally the mother decides the sister is the one most in need and more or less throws Ichiko out onto the streets. She gets herself a little apartment and a job in the 100 yen store where she’s perved over by a sleazy colleague and amused by a crazy old lady who turns up each night to help herself to the leftover bento.

Ichiko also becomes enamoured with a frequent customer who they nickname “Banana Man” because he just comes in, buys a ridiculous number of bananas, and leaves without saying anything. He’s even more awkward than Ichiko though he seems to kind of like her too. Banana Man is an amateur boxer and eventually ends up staying in Ichiko’s apartment following a rather complicated chain of events. When this too goes wrong, Ichiko decides to try her hand at boxing herself, hoping to make the next set of matches before she passes the age threshold.

We aren’t really given much of a back story for Ichiko, other than that her polar opposite sister thinks she’s too much like their father who also seems to be a mildly depressed slacker only now in early old age. Her mother is at the end of her tether and her sister probably just has problems of her own but at any rate does not come across as a particularly sensitive or sympathetic person. Getting kicked out at this late stage might actually be the best thing for Ichiko though it’s undoubtedly a big adjustment with her family offering nothing more than possible financial support.

Working in the 100 yen store isn’t so bad but it doesn’t really suit Ichiko with her isolated shyness and lack of work experience. Mind you, it seems like it doesn’t suit anyone very well as her manager quits right away and her only co-worker is a lecherous criminal who literally will not stop talking or take no for an answer. Ichiko’s only real relationship is with Banana Man but even this is strange with Ichiko becoming infatuated and coming on too strong for the rather immature amateur boxer who’s just hit the end of his career. If Ichiko is going to get anywhere she’ll have to do it on her own and on her own terms, no one is going to help her or be on hand to offer any kind of life advice.

That is, until she starts boxing where she gets some coaching, if only inside the ring. The gloves give her a purpose, in getting to a real match before the age limit passes (it’s 32 and she is already 32) she finally has something concrete to work towards and strive for. She just wants to win, once, after all the awful and humiliating things that have happened to her, she just wants to hit back. Even if she falls at the final hurdle, these seemingly small elements have caused a sea change within her. No longer holed up at home, too fearful to engage with anything or anyone, Ichiko has her self respect back and can truly stand on her own two feet.

Indeed, the film might well be called sympathy for the loser – what attracts Ichiko to the sport to begin with is the mini shoulder hug at the end between the victorious and the defeated. With the idea that it’s OK to lose, there are no hard feelings between athletes and even a mutual respect for those who’ve done their best even if they didn’t quite make it, this moment of catharsis seems to give Ichiko the connection she’s been craving. However, the film’s ending is a little more ambiguous and where this rapid transformation of the “100 yen kind of girl” might take her may be harder to chart.

100 Yen Love is Japan’s submission for the 2016 Academy Awards.

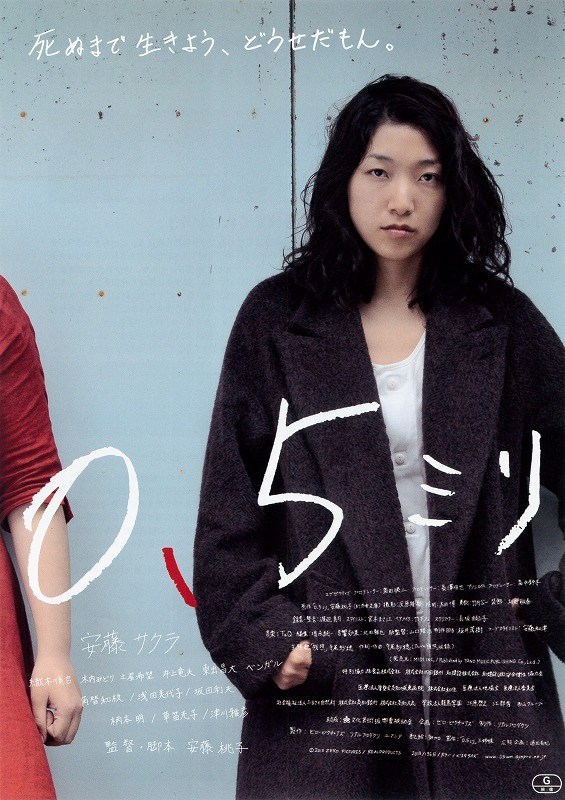

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.