When Godzilla emerges from the waves in Takashi Yamazaki’s entry into the classic tokusatsu series Godzilla Minus One (ゴジラ-1.0), he does so as an embodiment of wartime trauma most particularly that of the hero, Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki), a kamikaze pilot who failed die. Some might call his actions cowardice, returning to base siting engine trouble rather than doing what others regard as his duty, though the film implies it’s simply a consequence of his natural desire to live, a desire which the tenets of militarism which in essence a death cult insisted he must suppress.

But for Koichi as he’s fond of saying the war never ends. He’s trapped in a purgatorial cycle of survivor’s guilt and internalised shame, feeling as if he has no right to a future because of the future that was robbed from other men like him because of his refusal to sacrifice his life. When he first encounters Godzilla on a small island outpost, he is ordered back into his plane to fire its guns at him but freezes while the rest of the men, bar one, are killed. Tachibana (Munetaka Aoki), a mechanic who had already branded Koichi a treacherous coward, gives him a packet of photographs belonging to the dead men each featuring the families they were denied the opportunity to return to. Photographs on an altar become a motif for him, though he has none for his parents who were killed when their house was destroyed by the aerial bombing of Tokyo. A surviving neighbour similarly blames him, directly aligning Koichi’s act of selfish cowardice with the razing of the city.

The return of Godzilla is literal manifestation of his war trauma which he must finally confront in order to move into the new post-war future that’s built on peace and solidarity rather than acrimony and resentment for the wartime past. But then again, the film situates itself in a fantasy post-war Tokyo in which the Occupation is barely felt and the government, which mainly consisted of former militarists, is also absent. Both the US and the Japanese authorities refuse to do anything about Godzilla because of various geopolitical implications making this a problem that the people must face themselves, though they largely do so through attempting to repurpose rather than reject the militarist past. Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka), a scientist who worked on weapons production during the war, gives a rousing speech in which he explains that this time they will not pointlessly sacrifice their lives but instead fight to live in a better world which is all very well but perhaps mere sophistry when the end result is the same.

Called back by their old commander, many men say they will not risk their lives or abandon their families once again because they have learned their lessons but others are convinced by the message that they must face Godzilla if they’re ever to be free of their wartime past. Koichi wants vengeance against Godzilla but also to avenge himself by doing what he could not do before. The film seems to suggest that this time it’s different because he has a choice. No one has ordered him to die, and he is free to choose whether to do so or not which is also the choice of being consumed by his war trauma or overcoming it to begin a new life in the post-war Tokyo that Godzilla has just destroyed.

Despite the desperation and acrimony he returns to, Koichi maintains his humanity bonding with a young woman, Noriko (Minami Hamabe), who agreed to take care of another woman’s child. Even the neighbour, Sumiko (Sakura Ando), who first rejected Koichi and is suspicious of Noriko, willingly gives up her own rice supply for the baby proving that in the end people are good and will help each other even if that seems somewhat naive amid the realities of life in the post-war city ridden with starvation and disease. In any case, it’s this solidarity that eventually saves them, Godzilla challenged less by a pair of large boats than a flotilla of small ones united by the desire to finally end this war. Like Yamazaki’s previous wartime dramas The Eternal Zero and The Great War of Archimedes, the film espouses a lowkey nationalism mired in a nostalgia for a mythologised Japan but as usual excels in terms of production design and visual spectacle as the iconic monster looms large over a city trapped between the wartime past and a post-war future that can only be claimed by a direct confrontation with the lingering trauma of militarist folly.

Godzilla Minus One opens in UK cinemas 15th December courtesy of All the Anime.

International trailer (English subtitles)

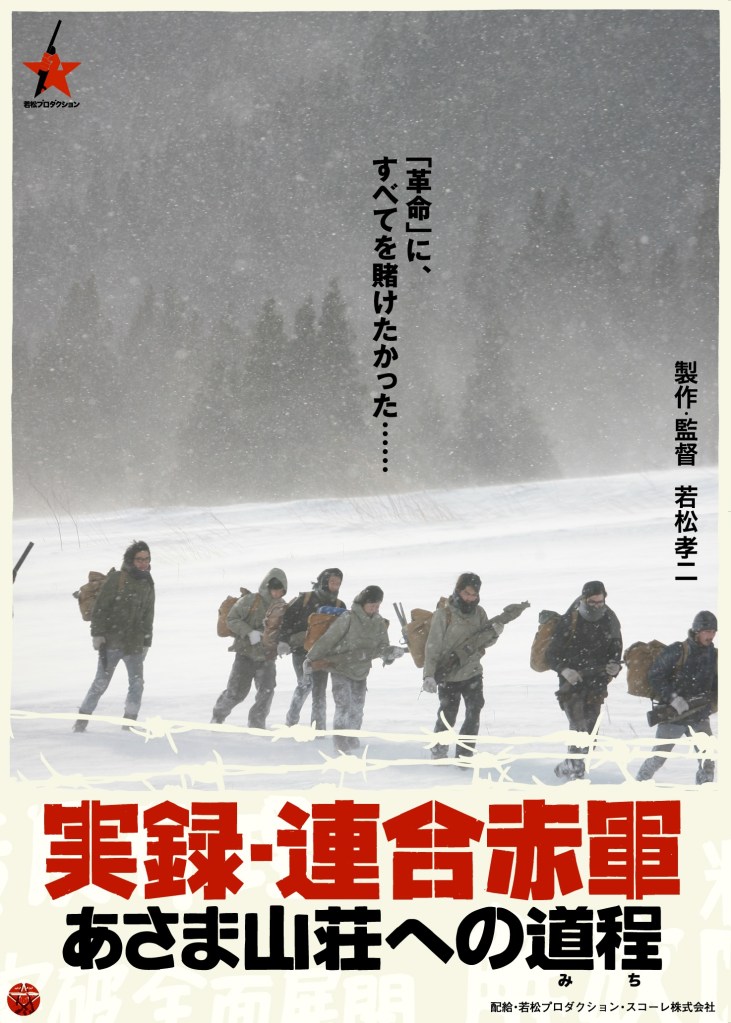

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.