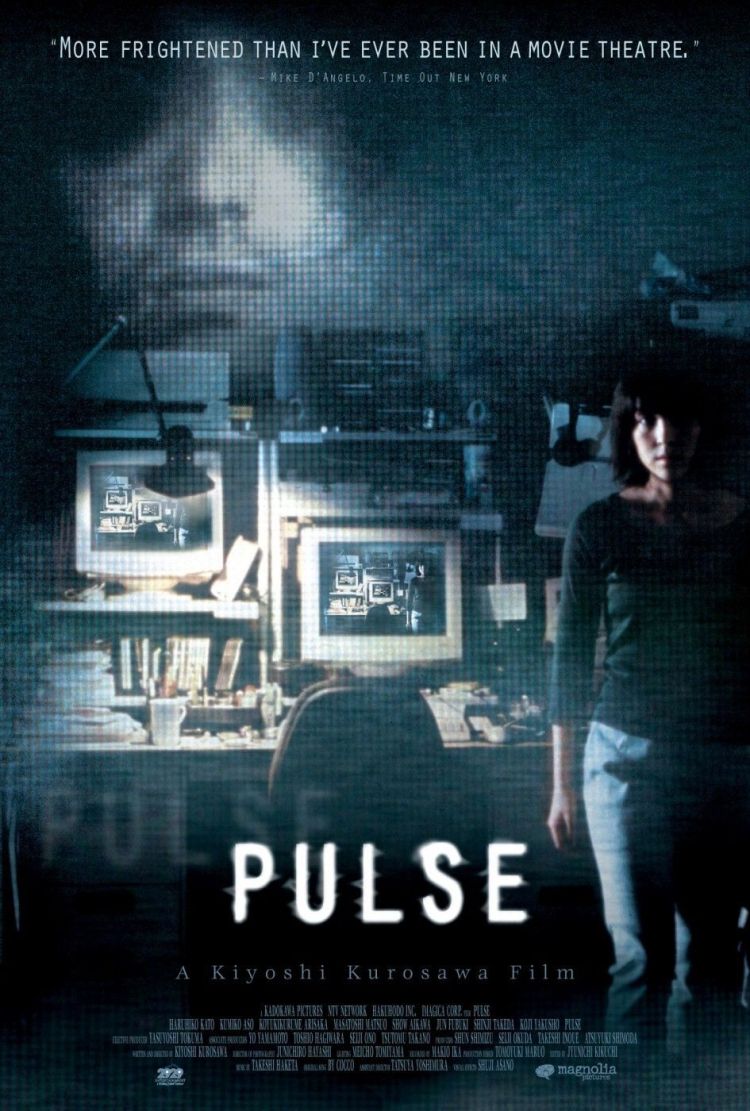

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

The end of the world starts with a young man staring at his computer screen and the strange images it conjures of the only half alive. Michi (Kumiko Aso), a young woman working at a rooftop plant centre, is dispatched to find out what’s happened to a colleague, Taguchi (Kenji Mizuhashi), who has some essential information stored on a floppy disk. Arriving at his flat she finds him distracted, informing her that the disk is somewhere in a pile scattered on the desk before disappearing off somewhere else. Having found what she came for, Michi looks for Taguchi to say goodbye but finds him hanged in an adjacent room. Barely reacting, Michi deals with the police before meeting up with her colleagues to relate the news, leaving each of them stunned. Another colleague, Yabe (Masatoshi Matsuo), then receives a strange phone call as a distorted voice repeatedly utters the words “help me”.

Meanwhile, economics student Kawashima (Haruhiko Kato) is attempting to set up this new fangled internet thing in his dorm but failing miserably. When he finally gets online and is greeted with the message “would you like to meet a real ghost?” he thinks he’s done something very wrong and hurriedly shuts his computer down. Seeking advice in the uni computer club he gets to know IT professor Harue (Koyuki) who tries to help him but may be beyond help herself.

The Japanese title, “Kairo”, literally means “circuit”, a fixed path of connectedness along which something flows continuously. A “pulse” is itself a circuit, or more accurately an observation of a fixed point in motion along it which maybe continuous or finite. Pulse, in its most immediate meaning is the life force by which we live, the thing which defines the states of life and death, but the “circuit” here is bigger than that which exists in one body alone, extending across the great confluence of humanity, or at least of that still regarded as “living”.

When Harue attempts to fix Kawashima’s internet she prompts him about why he wanted it in the first place (it was hardly necessary back in the still largely analogue world of 2001). He seems confused and replies he doesn’t quite know, it’s just that everyone seemed to be into it. Harue thinks she has his number – he thought he could use it to connect with people, but, she says, that is hopeless, people don’t truly connect, we all live in our separate bubbles. Harue is the most classically “disconnected” of our protagonists. Never having felt at home in the world, she talks of a lifelong fascination with the idea of death as a portal to another one in which it might be possible to live happily with others, only to realise as a teenager that it might also be a gateway to a land of perpetual nothingness and isolation. Terrified of being alone yet unwilling to submit herself to the inherent risks of connection, Harue exists in a permanent state of embittered longing and anxiety in which the cold embrace of death may prove the the only companion she will ever allow.

Harue may be an extreme case but she’s not the only example of disconnected youth. Michi, is also aloof and isolated – a child of divorced parents who has a close if imperfect relationship with her mother (Jun Fubuki) and an absent father she has already rejected. She says she’s OK in the city because she has her friends prompting her mother to warn her that she’s too trusting, too blind to the dangers of city life. Michi’s connections may turn out to be shallow, but unlike Harue she remains broadly open, seeking physical connections rather than digital ones. She visits her friend’s apartment, and makes a point of chasing after Yabe even after her boss warns her that friendly words can wound and that wounding a friend is also an act of self harm. Compelled to travel onwards, she resolves to keep on living, continue seeking connections until there are no more left to seek.

Kurosawa’s world is one of essential interconnectedness which finds itself frustrated by a mysterious forces leaking in. Yet the ghosts are not all on the other side, these are people who are spiritually dead while physically alive – isolated, defined by routine and expectation, and endlessly unfilled. “Trapped inside their own loneliness” as one character puts it, the disappeared gain a kind of immortality but it’s one filled with eternal longing and isolation. These “broken connections” are continually in search of vulnerable ports, flooding a system which has already begun to fail, and threatening to destroy that which they seek. The “ghosts” have destroyed the machine, but Kurosawa’s apocalyptic conclusion, melancholy as it seems to be, offers as much a hope for rebirth as it does a condemnation to existential loneliness.

Now available on blu-ray from Arrow Films!

Arrow release EPK

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.

Koji Wakamtasu had a long and somewhat strange career, untimely ended by his death in a road traffic accident at the age of 76 with projects still in the pipeline destined never to be finished. 2008’s United Red Army (実録・連合赤軍 あさま山荘への道程, Jitsuroku Rengosekigun Asama-Sanso e no Michi) was far from his final film either in conception or actuality, but it does serve as a fitting epitaph for his oeuvre in its unflinching determination to tell the sad story of Japan’s leftist protest movement. Having been a member of the movement himself (though the extent to which he participated directly is unclear), Wakamatsu was perfectly placed to offer a subjective view of the scene, why and how it developed as it did and took the route it went on to take. This is not a story of revolution frustrated by the inevitability of defeat, there is no romance here – only the tragedy of young lives cut short by a war every bit as pointless as the one which they claimed to be in protest of. Young men and women who only wanted to create a better, fairer world found themselves indoctrinated into a fundamentalist political cult, misused by power hungry ideologues whose sole aims amounted to a war on their own souls, and finally martyred in an ongoing campaign of senseless death and violence.