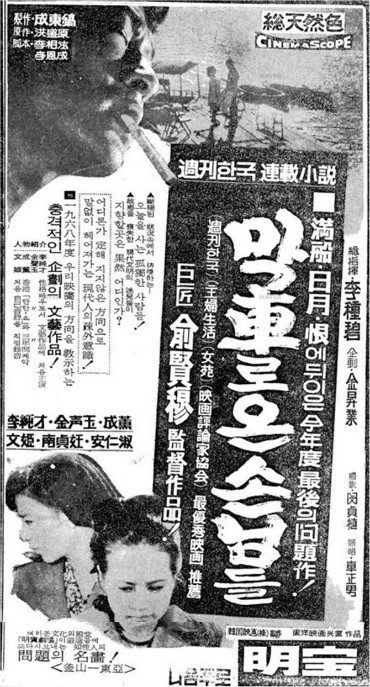

Despite ongoing social and political oppression, the Korea of the 1960s was an upwardly mobile world in which increasing economic prosperity and global ambition was beginning to offer the promise of financial stability and a life of comfort to millions of young men and women, albeit at a price. Yu Hyun-mok, often thought of as among the most intellectual of “golden age” film directors, was a relatively infrequent visitor to the “literary film” but Guests of the Last Train (막차로 온 손님들 / 막車로 온 손님들, Makcharo on Sonnimdeul, AKA Guests Who Arrived on the Last Train), adapted from a novel by Hong Seong-won, is perhaps comfortably in line with his career long concerns in its focus on those who for one reason or another have been running to catch the rapidly departing train of modernity, pulling themselves on board just it prepares to pull away. A disparate tale of three men and their respective love interests, Yu’s film once again rejects the consumerism of the modern society in its cold and lonely search for soulless acquisition and finds comfort only in the fragile connections between the lost and hopeless.

Despite ongoing social and political oppression, the Korea of the 1960s was an upwardly mobile world in which increasing economic prosperity and global ambition was beginning to offer the promise of financial stability and a life of comfort to millions of young men and women, albeit at a price. Yu Hyun-mok, often thought of as among the most intellectual of “golden age” film directors, was a relatively infrequent visitor to the “literary film” but Guests of the Last Train (막차로 온 손님들 / 막車로 온 손님들, Makcharo on Sonnimdeul, AKA Guests Who Arrived on the Last Train), adapted from a novel by Hong Seong-won, is perhaps comfortably in line with his career long concerns in its focus on those who for one reason or another have been running to catch the rapidly departing train of modernity, pulling themselves on board just it prepares to pull away. A disparate tale of three men and their respective love interests, Yu’s film once again rejects the consumerism of the modern society in its cold and lonely search for soulless acquisition and finds comfort only in the fragile connections between the lost and hopeless.

The film opens behind a train station where a young woman, Bo-yong (Bo-yong), staggers and stumbles, grasping for something to hold on to but hardly able to stand. Eventually a man, Dong-min (Lee Soon-jae), turns up and tries to hail a taxi. Noticing the distressed woman, he manages to get her into a car and when she tells him she has nowhere to go, takes her home with him. Dong-min is currently off work with an illness which turns out to be terminal lung cancer and has only a few months left to live as a second opinion from his doctor friend, Kyeong-Seok (Seong Hoon), makes clear. Kyeong-seok is also facing a problem with a female patient, Se-jeong (Nam Jeong-im), suffering a nervous complaint after losing her wealthy husband and subsequently being hounded by her relatives over the inheritance. When Se-jeong leaves the hospital the pair end up having an affair but the money continues to present a problem – neither of them want the hassle of dealing with it. Meanwhile, Dong-min and Kyeong-seok reunite with another old friend, Choong-hyeon (Kim Seong-ok), who has just returned from Japan apparently having become fabulously wealthy. Choong-hyeon has pretensions of becoming an avant-garde artist, but is unable to get over his ex-wife who has left him to become a famous actress.

Each of the three men is in someway arrested, unable to move past something towards the future rapidly rolling away from them like a train leaving the station. Dong-min’s depression and listlessness is understandable given that he’s facing a terminal illness and knows that he has already reached the end of the line. Yet his ennui began long before. Kyeong-seok, describing his friend to a colleague, disapprovingly remarks that he used to be a mild-mannered bank teller but left to become a freelance translator and journalist. Unable to put up with the stringent, high pressure world of work Dong-min removed himself from it to try and grasp his freedom only to remain dissatisfied and eventually defeated by a cruel and arbitrary illness. Even so he retains his human feeling as demonstrated by his decision to help Bo-yong rather than leave a vulnerable woman alone to suffer on the streets. Staring blankly at the calendar on his wall, avoiding tearing off the sheets which serve as an all too obvious symbol of his limited time, he falls slowly in love with the woman who remains at his side whilst knowing that his existence is futile and doomed only to tragedy.

Kyeong-seok, by contrast, is merely disaffected. Dragged into a relationship with Se-jeong originally unwillingly, what he resists is responsibility. He wants to help her, but he does not want to get involved with her complicated familial and financial problems. As so often in Yu’s films, money is the root of all evil, presenting barriers between people where there should be none. Neither Kyeong-seok or Se-jeong are very interested in the money for its own sake, they want only simple lives of adequate comfort and emotional fulfilment – something which the hassle of dealing with other people’s money hungry machinations will actively destroy.

Money has also, in a sense, destroyed Choong-hyeon’s hopes though more through his misplaced faith in its ability to buy him back what he’s lost. His relationship with his wife is clearly over, she has chosen something else which is her right and privilege, but Choong-hyeon can not accept it and continues to look for her in all he does. Attempting to become an “artist” himself, he uses his money to get himself a show featuring his avant-garde pop art creations but neither of his friends rate his work or is careful enough about his feelings to avoid criticising it. Choong-hyeon spirals out of control, becoming dangerously obsessed with a schoolgirl he somehow wants to imagine as his wife. Dong-min and Kyeong-seok suspect that he will kill himself, but by this point they aren’t sure if they should care. What would they be saving him for? There is no possible salvation – no one can save anyone else, and no one can save themselves. Each is an individual and can offer no excuses. Love and friendship are but scant comfort in a cold and lonely world.

Meanwhile, the women continue to suffer in silence. Yu chooses to focus on his trio of male misfits rather than the pair of unlucky women whose story lies at the centre of the narrative. Se-jeong married an older man for apparently legitimate reasons but the marriage was unsuccessful and also ruined her friendship with her husband’s daughter who, unsurprisingly, turns out to be Bo-yong. Looking for love and not money, Se-jeong is only holding on to her inheritance in the hope of someday reconciling with Bo-yong and handing it all to her. Meanwhile, Bo-yong has been on the run from her former life. Once an air stewardess, Bo-yong dropped off the radar when a former fiancé planted drugs in her suitcase and got her sent to prison. Like Se-jeong she is looking for support and companionship and finds it in the kind if melancholy Dong-min, vowing to stay by his side even if she knows their time it limited. The two women are eventually “reunited” at a wedding, but the crowd keeps them apart, breaking into factions fighting over the inheritance that neither Se-jeon or Bo-yong actually want.

Yu declines to tell us whether the women are eventually able to meet and repair their friendship, but he does make clear that both have rejected the superficial comforts of wealth in asking for a small and simple life with their respective partners. In this he offers both hope and despair. The couples are rejecting the new future their nation has planned for them, yearning for small comforts and an end to their loneliness and struggling to find it in an increasingly alienated world. Bo-yong, at least, steps forward to grasp her chance at happiness however small it maybe, waiting for the train and seeing red lights change to green only when her gesture of sincerity is finally accepted.

Available on DVD as part of the Korean Film Archive’s Yu Hyun-mok boxset. Not currently available to stream online.