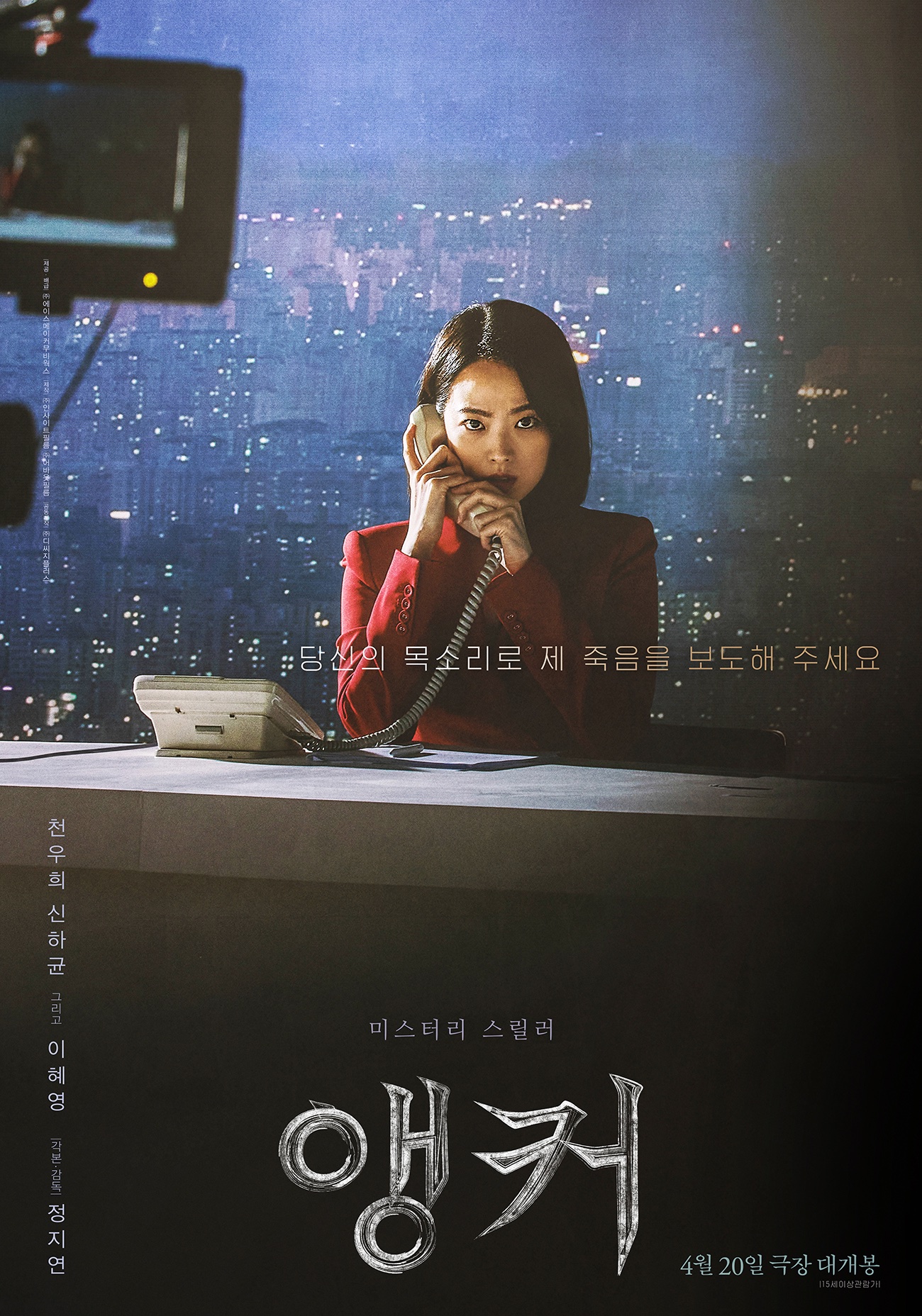

A successful newsreader’s sense of reality begins to fracture when she ends up becoming part of the story in Jeong Ji-yeon’s twisty B-movie psychological thriller, The Anchor (앵커, Anchor). As much about mothers and maternal anxiety as it is about a patriarchal and conservative society, Jeong’s eerie journey through the psyche of a traumatised woman is also a quest for identity and a search for the self as the heroine rails against her role as a mere conduit for the thoughts and will of others.

In her mid-30s, Sera (Chun Woo-hee) is a popular anchor helming the most important news report of the day. Yet she’s facing a challenge from a younger rival who is not a trained presenter but a respected reporter who can bring a degree of editorial authority to the desk which her polished delivery cannot. As one of her bosses puts it, it’s the way that things are going which Sera seems to know seeing as he also remarks that she’s been trying to gain experience as a reporter so that she can be a “real anchor”. As it stands, her job is mostly to look presentable and support the male lead reading out words other people have written presented to her by autocue. Her mother (Lee Hye-young) is always needling her, insisting that she can’t afford to let her guard down even for a moment if she wants to keep her spot while further fuelling her sense of futility in suggesting that even becoming a news anchor may not have been her decision in the first place so much as in service to her mother’s desire for vicarious success.

When a strange woman, Mi-so (Park Se-hyeo), calls in to the station one day insisting on speaking with Sera directly it seems like the perfect opportunity to prove her credentials as an investigative reporter but her male colleague immediately shuts the conversation down writing off the woman’s claims that she’s being harassed by an unknown aggressor as a prank call from a crazed fan. Sera follows his lead and in any case has to read the news, but something about the woman’s story disturbed her so she decides to check out her address and is shocked to discover the woman’s daughter dead in the bath and the woman herself hanging in her closet with her phone still in her hand. Perhaps echoing her own fragile mental state, Sera is haunted by the image of the woman hanging but does not seem to feel particularly guilty or responsible for her death in not following up immediately in case she and her daughter could have been saved so much as determined to turn the case into her personal crusade to decrease the likelihood of them kicking her off the desk.

The desire to investigate the case herself is in part a desire to assert her own identity as distinct from that projected onto her by her overbearing mother and chauvinistic husband who insists that her mother is controlling her but in reality just wants to control her himself. Min (Cha Rae-hyung) keeps badgering her about starting family but seems oblivious to her wishes though the couple appear to have been separated for some time only keeping up appearances to avoid the possible fallout from the scandal of divorce. Becoming a mother is in a way to lose one’s own identity especially in a society such as a Korea’s in which women who bear children stop hearing their own name, addressed only as so and so’s mum rather in their own right. It may partly be this sense of erasure which drives the resentment which exists between mother and child along with a persistent social stigma against women raising children alone especially if born out of wedlock. The idea of a woman seeking fulfilment outside of the home is still to some taboo with a strong social pressure for women to abandon their own hopes and desires and devote themselves entirely to the role of “mother”.

On trying to decide how to frame the case, the editorial board is torn between viewing Mi-so as a victim of unjust societal pressures and condemning her as an evil woman who murdered her daughter and then herself, the police having decided that there was no third party involved despite Mi-so’s claims of an intruder. Even with a more compassionate framing, the message is pity rather than a drive for social change in which women like Mi-so who appears to be incredibly young, little more than a child herself, could get the help they need. Sera becomes convinced that a creepy psychiatrist (Shin Ha-kyun) specialising in hypnotism is somehow responsible though he frames the mysterious intruder as a kind of phantom, a manifestation of buried trauma ratting the doors trying to get in or else a convenient “entity” that allows the hauntee to deny their responsibility or reality. In any case, Sera’s investigations take her to a dark place but eventually arrive in a kind of psychological wombscape in which she must finally kill the image of the mother in herself in order to escape her mother’s house in a symbolic vision of birthing a new self having reclaimed her individual identity. Elegantly lensed and filled with visions of refracting mirrors reflecting Sera’s identity crisis Jeong’s eerie psychodrama eventually allows its heroine to find her own way out of unresolved trauma if only ironically.

The Anchor screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Vengeance is a doubled edged sword, it cannot help but wound the wielder. The heroine of Jung Byung-gil’s ironically titled The Villainess (악녀, Aknyeo) has more to be revenged of than even she knows. Yes, the narrative beats are familiar and Jung has clearly drawn inspiration from Luc Besson’s seminal hit woman movie La Femme Nikita as well as the long history of female revenge films from Lady Snowblood to Kill Bill, but he does it with style and style is always hard to argue with. A new kind of action cinema, The Villainess makes a performer of its camera, darting frantically like an animal on the run and then drifting listlessly between dreamlike visions of half remembered traumas. Jung remains firmly in B-movie territory but owns it, unafraid to embrace the genre’s more extreme qualities and all the better for it.

Vengeance is a doubled edged sword, it cannot help but wound the wielder. The heroine of Jung Byung-gil’s ironically titled The Villainess (악녀, Aknyeo) has more to be revenged of than even she knows. Yes, the narrative beats are familiar and Jung has clearly drawn inspiration from Luc Besson’s seminal hit woman movie La Femme Nikita as well as the long history of female revenge films from Lady Snowblood to Kill Bill, but he does it with style and style is always hard to argue with. A new kind of action cinema, The Villainess makes a performer of its camera, darting frantically like an animal on the run and then drifting listlessly between dreamlike visions of half remembered traumas. Jung remains firmly in B-movie territory but owns it, unafraid to embrace the genre’s more extreme qualities and all the better for it.