“I told you to shut up about that,” Kokoa’s mother (Kumi Takiuchi) tells her after she gets caught with two other children trying to start an environmental revolution by releasing cows from their paddock. It’s not difficult to see why Kokoa (Ruri) feels so strongly about global warming even if it’s probably her home environment that she most wants to change given adult indifference to climate issues, though Mipo O’s charming family dramedy How Dare You? (ふつうの子ども, Futsu no Kodomo) is less about the issues themselves than the relationships between the children and the adults around them.

The point being that Kokoa hates adults for trashing the world and creating an environment in which she feels it’s impossible to live. Fellow student Yuishi (Tetta Shimada) is drawn to her Greta Thunberg-style speech in class having just embarrassed himself with an essay about his toilet habits and suddenly develops an interest in the environment as a means of getting close to her. Which isn’t to say that he didn’t really care before. In this semi-rural area, he and his friends still go outside every day to catch woodlice to feed his friend Soma’s lizards, and Yuishi is also very keen on animals in general. He’s sympathetic to the cause, but on the other hand, is only really into this because of Kokoa who pretty much ignores him in favour of class bad boy Haruto (Yota Mimoto) who tells her that they need to take “action” to wake the adults up or no one’s going to listen to a bunch of kids whining about methane emissions.

There is something pleasantly old-fashioned about their tactics which include cutting letters out of magazines to make protest signs they hang up all over town telling people not buy so much stuff, eat meat, or drive cars. But while the other two are increasingly emboldened their actions and their revolutionary activities begin to get out of hand, Yuishi finds himself conflicted. When they spot similar signs springing up made by other kids they don’t know, Kokoa and Haruto are annoyed rather than pleased that more people are joining the cause. Yuishi agrees with a sign saying people should catch the bus because it’s better than driving a car even if buses also pollute while Haruto opposes it. But he also points out that the firework rockets Haruto has bought for another action give off CO2, so perhaps they shouldn’t use them. He tries to deescalate and avoids becoming radicalised, but is eventually bullied into going along with the other two and suggests releasing the local farmer’s cows as their next protest assuming it’s a “nice” thing to do and less aggressive than some of Haruto’s ideas.

But they’re still just children and don’t really understand the consequences of their actions. After all, what’s a wild cow supposed to do? It doesn’t occur to them that the cows could get hurt or end up causing accidents and damage, let alone that they may alienate the local community who are already fed up with their stunts because it’s affecting their livelihoods. Of course, this is also part of the problem. The adults ignore the children because what they’re saying is inconvenient for the way they live their lives under capitalism which isn’t something they think they could change even if they wanted to which they likely don’t. Yuishi’s sympathetic mother is forever reading books about how to raise children well, and so she tries to listen to Yuishi but also “corrects” him in subtle ways like hiding meat in his spring roll after he tells he wants to give up eating it for the environment. Though she may have correctly assumed that he’s not really serious about it and tells him what she’s done after his first bite of the spring roll, there’s no getting around the fact that just as Kokoa said she’s not really listening. Nor does she sort her rubbish and recycling responsibly. When Yuishi looks up global warming on his tablet, his mother remembers being told about this at school too, which just goes to show how long this has been going on and how easily everyone forgot about the ozone layer panic of 1980s and 90s.

Nevertheless, the gradual escalation of the children’s activities towards something akin to ecoterrorism echoing the student protest movement on the 1960s satirises the dangers of radicalisation especially as neither of the boys are really invested in the cause and are only there because they’re each drawn to Kokoa who remains intense and implacable. Their true natures are exposed when they’re caught with only Yuishi stoic and remorseful, admitting it was his idea to release the cows and that he did it because he liked Kokoa and wanted her to like him back, while Haruto spends the entire time crying in his mother’s arms and Kokoa glares at everyone while reciting environmental statistics. Maybe she isn’t overly invested either so much as trying to regain control over her life and using cold hard facts as an escape from her overbearing mother who liked her better when she was “sweet” and ‘cute” and never asked any inconvenient questions. Even so, there is something very charming about the children’s earnestness that’s largely lost on the well-meaning adults around them who may be trying their best in lots of other ways but have already given in to the idea that the world can’t be changed and nothing they do makes a difference so there’s no point doing anything. Yuishi at least has learned some valuable lessons, if only that things go better when you’re straightforward and honest your feelings even if it might be embarrassing in the moment.

How Dare You? screens 20th July as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene.

Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene. In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.

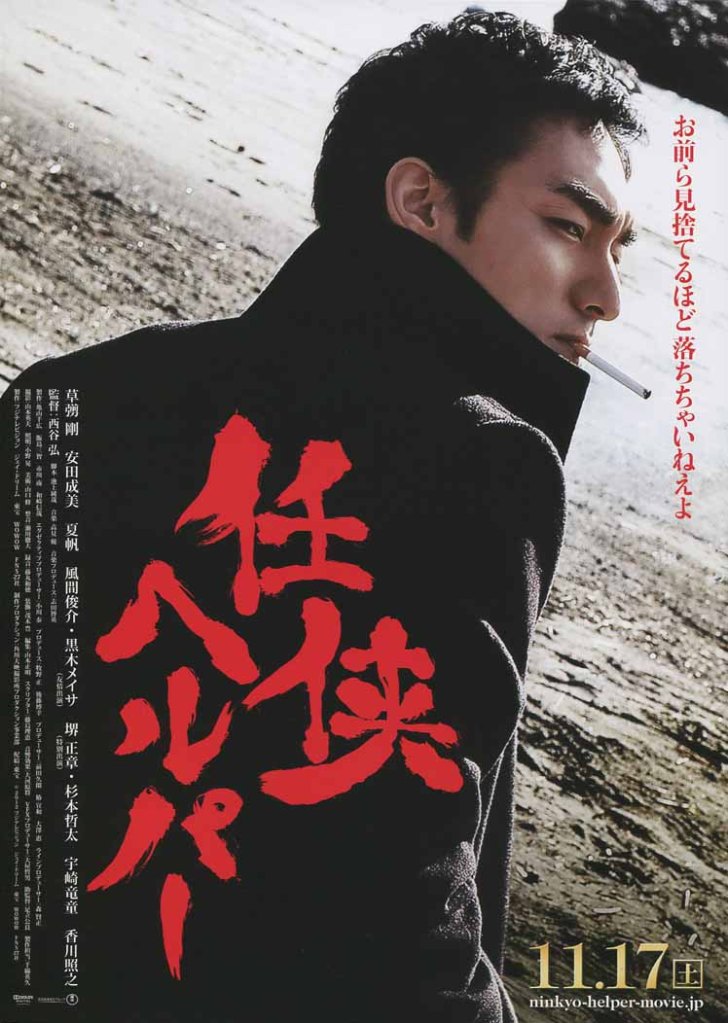

In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.