A young man with blond hair and blue eyes stands out in North Korea, though Isak speaks the language fluently, if with a Southern inflection, and tries to make friends with those around him but is generally kept at arms’ length by those who struggle to understand his motivations. As his boss tells him, foreigners are destined to be lonely, but that goes for the local community too. Constant observation has a curiously isolating quality, as if you were always under a spotlight with every word and gesture scrutinised for potential signs of dissidence, though ironically you are never really alone.

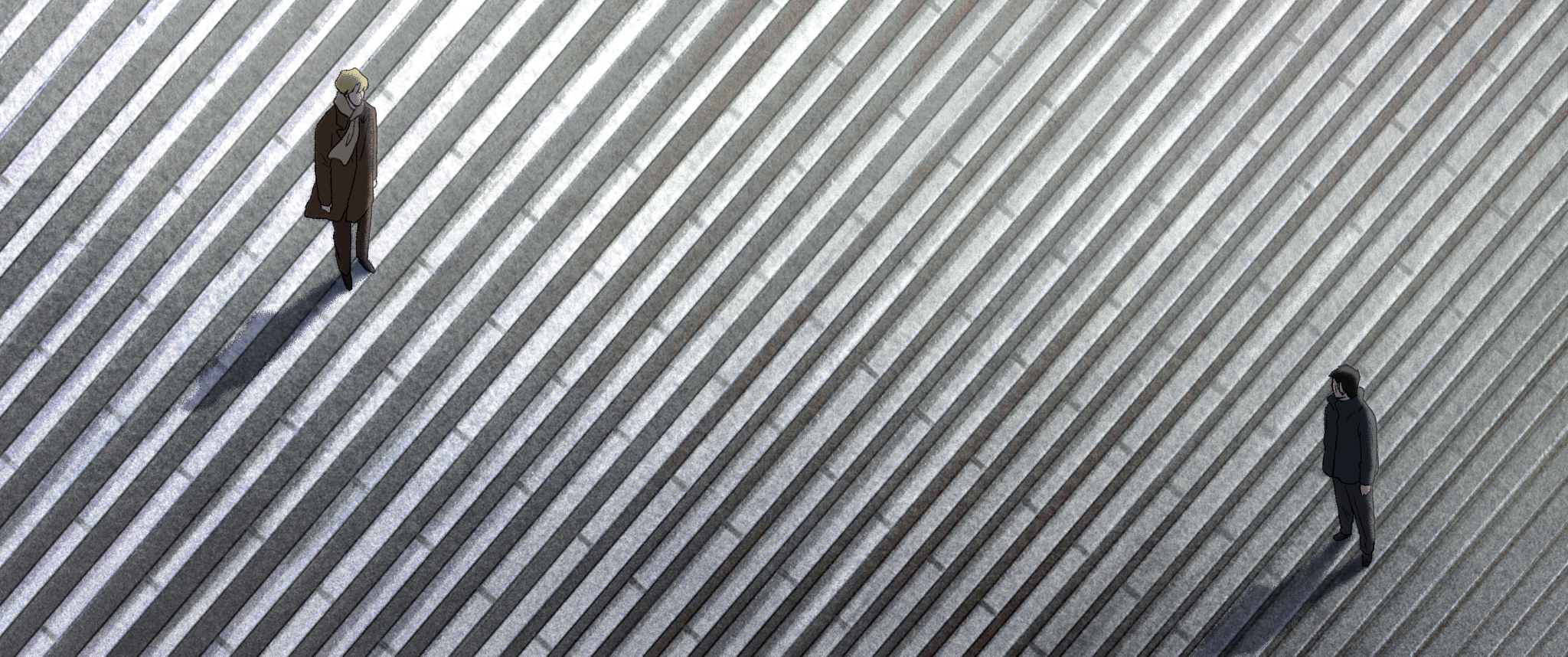

Set in the secretive Communist state, Kim Bo-sol’s melancholy animation The Square (광장, Gwangjang) is in many ways about the dehumanising effects of a surveillance state and the pressures of living in a society in which it becomes impossible to communicate with other people because every interaction has the potential to destroy your life. Everyone you meet is a potential enemy and betrayal lurks around every corner. To begin with, the perspective is Isak’s. He looks at North in the same way we do. Scenes familiar from North Korean travelogues such as the underground station and passages with social realist artwork featuring soldiers smashing capitalism dominate, but he also as an abstracted perspective in trying to reconcile this place with that of his Korean grandmother who followed his grandfather to Sweden before the Korean War. A Swede should eat Swedish food, she ironically tells him in a letter included with a care package full of tinned sausages, through he washes them down a few glasses of soju.

He tries to share them with Myeong-jung, ostensibly his interpreter though Isak is in the North to work as a translator himself and doesn’t really need one despite Myeong’s advanced skills in both English and Scandinavian languages. Myeong-jung always rudely rebuffs his attempts at friendship and appears displeased when Isak tells him he’s trying to get his stay extended. This is partly because of the tense situation, it would be difficult for Myeong-jung to be on friendly terms with a foreign diplomat without arousing suspicion, but also because Myeong-jung seems to have developed some genuine affection for Isak which makes his real job, monitoring him for signs of “harmful” behaviour, much more difficult. Myeong-jung lives in the apartment across the courtyard and has a camera trained on Isak’s window. Like the hero of the Conversation or the Lives of Others he’s become invested in Isak and has begun doctoring his reports to protect him after becoming aware that he has become romantically involved with a young woman who directs traffic for a living, Bok-joo.

Asked why he tried to help him, Myeong-jung replies that perhaps he was just “lonely” though there is something of a homoerotic tension in his relationship with Isak. After Isak drinks too much on realising that the woman he loves has been disappeared, Myeong-jung steps out of the shadows to rescue him and Isak rests his head on Myeong-jung’s back as they ride home, just as Bok-joo had while riding behind Isak on his bicycle. If that really were the case, his love is as futile as Bok-joo’s or perhaps more so. In any case, he’s right when he calls Isak naive. If their affair were exposed, Bok-joo could be in a lot of danger. His pursuit of her is selfish, and perhaps if he really loved her, the most sensible thing would be to avoid seeing her again. Isak seems put out when Bok-joo tells him she won’t leave with him because she doesn’t want to leave her country or her family for the complete unknown, but were she to do so it would also be selfish. Her family would be made to pay in her absence.

Then again, the worst thing that happens to anyone in this film is being exiled from Pyongyang and other than their loneliness, they do not seem to be particularly unhappy in the North and have no real desire to leave though arguably that’s because they are already resigned its futility. Isak asks Myeong-jung why he doesn’t apply to travel with his advanced language skills but Myeong-jung brushes the question off and replies he’s barely been out of the city let alone another country though his interest in Isak maybe a reflection of his desire for the world outside of the North. Isak, by contrast, asks himself if he could stay in the North forever to live with Bok-joo and make the reverse decision his grandmother once made though in the end the decision is not really his to make. He has to accept that love is an impossibility under such a repressive regime let alone love between a citizen and a foreigner and that the division will forever keep them apart. Whatever choice his grandmother had, Isak does not have any. But despite the melancholy setting of Pyongyang in the snow, there is a kind of warmth to be found that these connections were made at all even as Myeong-jung spins his wheels, riding in circles like Isak and listening to the DiscMan Isak left behind like an echo of a far off freedom.

Trailer (English subtitles)