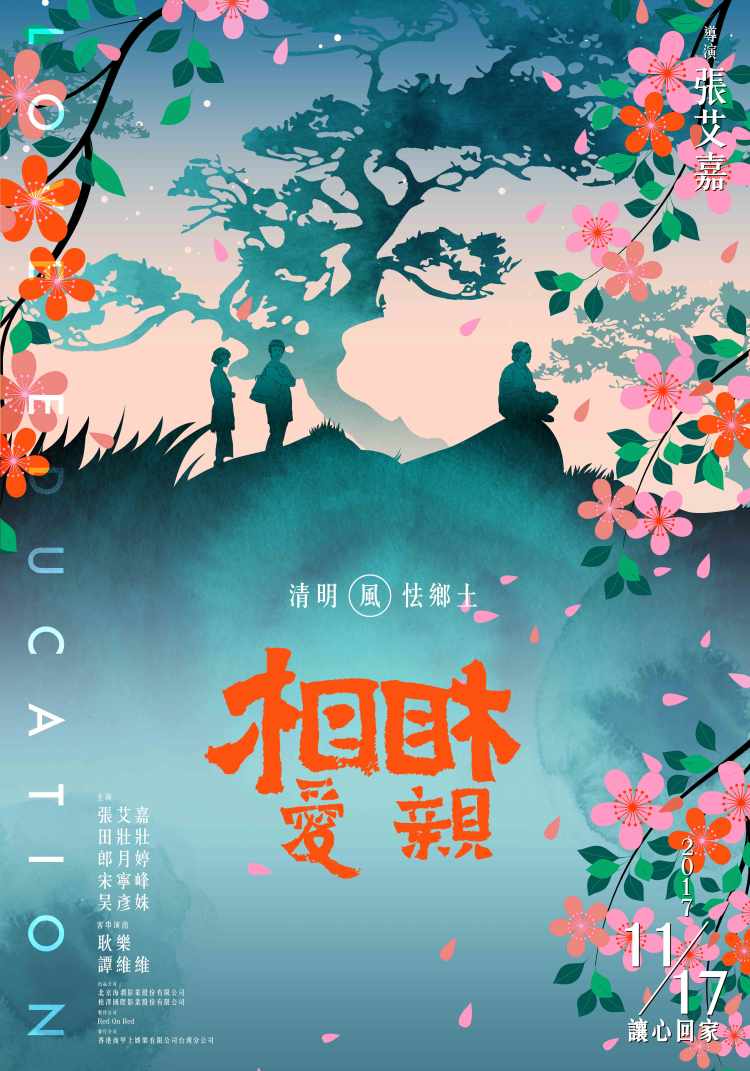

What is love? Who gets to define it, and should it be a force of liberation or constraint? Sylvia Chang attempts to find out in looking at the complicated, unexpectedly interconnected romantic lives of three generations of women who discover that nothing and everything has changed in the decades that divide them. While a bereaved daughter channels her own anxieties of impending mortality into a petty and hopeless quest to validate the true love history of her parents, a daughter battles an oddly familiar problem with her musician boyfriend, and an elderly village woman is forced to realise she wasted her life waiting for the return of a man who had so carelessly abandoned her. Mediated by a culturally specific argument over burial rites, Love Education (相愛相親, Xiāng ài xiāng qīn) is a meditation on the demands and obligations of love, both familial and romantic, as they inevitably change and mature across the arc of lifetimes.

What is love? Who gets to define it, and should it be a force of liberation or constraint? Sylvia Chang attempts to find out in looking at the complicated, unexpectedly interconnected romantic lives of three generations of women who discover that nothing and everything has changed in the decades that divide them. While a bereaved daughter channels her own anxieties of impending mortality into a petty and hopeless quest to validate the true love history of her parents, a daughter battles an oddly familiar problem with her musician boyfriend, and an elderly village woman is forced to realise she wasted her life waiting for the return of a man who had so carelessly abandoned her. Mediated by a culturally specific argument over burial rites, Love Education (相愛相親, Xiāng ài xiāng qīn) is a meditation on the demands and obligations of love, both familial and romantic, as they inevitably change and mature across the arc of lifetimes.

As Huiying’s (Sylvia Chang) elderly mother lies dying, she sinks into a vision of a bright summer’s day spent with her one true love who is already waiting for her in a better place. Huiying, a middle-aged school teacher facing semi-enforced retirement, is thrown into a tail spin of grief and anxiety in losing her mother, realising that it won’t belong before her daughter will in turn lose her. Weiwei (Lang Yueting), an aspiring TV journalist, remains unmarried and still lives at home though, unbeknownst to Huiying, is planning to move out and live with her aspiring rockstar boyfriend, Da (Song Ning). The plan is, however, thrown into confusion by the resurfacing of his ex, in the city with her son to compete in a cheesy TV singing contest. Meanwhile, Huiying has become obsessed with the idea of burying her mother alongside her father, only his body was sent back to his rural hometown, as is the custom, and so will need to exhumed and brought to the city. Unfortunately, Huiying’s father was technically a bigamist – he left an arranged marriage in the country to look for work in the city, “married” Huiying’s mother and never looked back. Huiying, determined to prove the “legitimacy” of her parents’ love seeks to reunite them in death, but Nana (Wu Yanshu) – the abandoned country wife, is hellbent on retaining the body, at least, of the man she married and thereby legitimising herself as a “true” wife.

Huiying’s grief-stricken descent into desperate obsession is a thinly veiled attempt to work through her own feelings of middle-aged dissatisfaction and anxiety on being violently confronted by her transition from a position of authority into a potentially powerless old-age. Her decades long marriage to Xiaoping (Tian Zhuangzhuang), a mild-mannered former teacher turned driving instructor, is comfortable enough but perhaps floundering as the couple contemplate their retirement and impending dotage. Huiying, mildly jealous of a elegant pupil who seems to have taken a liking to her husband, is also entertaining a mild crush on the father of one her own pupils while quietly feeling the distance that has inevitably grown between herself and her husband throughout the years. And so, she sets about “proving” that her parents’ romance was good and true, not only morally recognised but blessed by the state and legally approved.

This, however, proves more difficult than expected due to China’s rapid modernisation, series of political changes, high levels of bureaucracy and idiosyncratic way of issuing documentation. As her parents were “married” in the ‘50s, their union was approved by the local Communist authorities whose approach to record keeping was not perhaps as serious as might be assumed. The receipt for their license should be at the local block office, but they knocked that down. The papers were supposed to be moved to the town hall, but lacking resources they simply threw away all the documents from 1978 and before. Huiying’s parents belong to a past which has literally been thrown away, erased from history and regarded as an irrelevance by the current generation who think only of the future.

Meanwhile, Nana has been patiently waiting in her home town – a “good wife” by the standards of her rural society. Marrying Huiying’s father in an arranged marriage she has done all expected of her – looked after his family and then lovingly tended his grave despite the fact that he abandoned her after only a few months of marriage, not even bothering to tell her that he met someone else and wasn’t coming back. Nana, like Huiying, is desperate to legitimise her position to avoid the inevitable realisation that she has sacrificed her life for a set of outdated ideals.

Weiwei feels this most of all. Unlike her mother, she can’t forgive her grandfather’s moral cowardice in treating his first wife so cruelly. Building up an unexpected bond with the ironically named “Nana”, Weiwei is also forced to think about her own stalling relationship with Da who put his rockstar dreams on hold to stay with her rather than proceeding on to Beijing to try his luck there. Da, like her grandfather, has a past – in this case a childhood sweetheart with a young son and possibly territorial ambitions over a kind young man she has wounded through abandoning. Should Weiwei wait for Da, and risk ending up all alone like Nana, or should she end things now and give up on youthful romanticism for grown up practicality?

So bound up with the “legitimisation” of love, there’s an inevitable degree of possessiveness which creeps into each of the relationships – even that of Huiying and her daughter as she attempts to clip her wings to keep her close, but there’s also a kind of generosity in Chang’s direction which eventually allows them all to break away (to an extent) from an insecure need for validation to something bigger, warmer, and with more capacity for empathy and understanding. Quite literally a Love Education, Chang’s exploration of the romantic lives of three generations of women finds that though the times may have become more permissive nothing has become any easier. Nevertheless, there is comfort to be found in learning to appreciate the feelings of others, offering support where needed, and making the most of what you have while you have it in the acceptance that nothing is forever.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

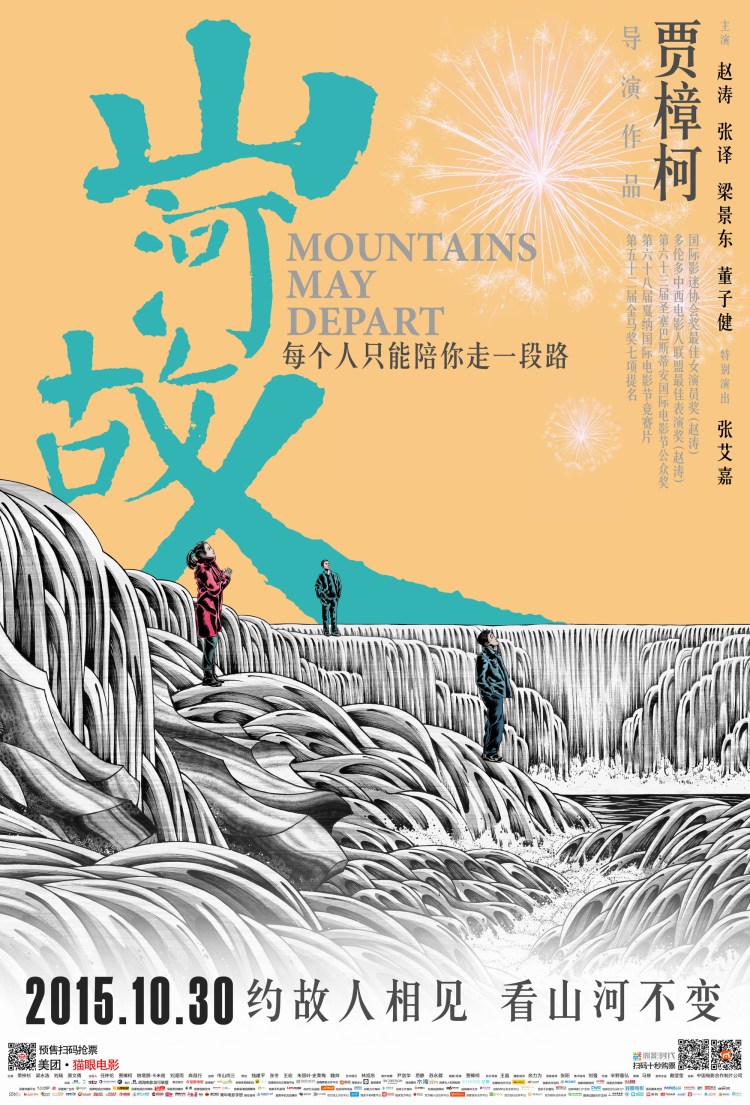

Jia Zhangke has made something of a career out of charting his nation’s history through the lives of ordinary people caught up in the business of living when everything about them is changing. Mountains May Depart (山河故人, Shānhé gùrén) isn’t the first of his films to span a comparatively wide period of time, though it is the first to venture into the “future” if only by a decade or so. Through a story of dislocation and isolation both cultural and personal, Jia has traversed the melancholy odyssey of those who grow up to discover that all the wrong choices have already been made.

Jia Zhangke has made something of a career out of charting his nation’s history through the lives of ordinary people caught up in the business of living when everything about them is changing. Mountains May Depart (山河故人, Shānhé gùrén) isn’t the first of his films to span a comparatively wide period of time, though it is the first to venture into the “future” if only by a decade or so. Through a story of dislocation and isolation both cultural and personal, Jia has traversed the melancholy odyssey of those who grow up to discover that all the wrong choices have already been made.