When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.

When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.

Chedeng (Gloria Diaz), apparently plotting the death of her sickly husband, is shocked to find him already gone when she takes him his breakfast. Shielded by the window which places her in the crematorium and her children outside it, Chedeng decides to make a shock announcement that comes as no surprise to her supportive best friend Apple (Elizabeth Oropesa). Standing front and centre and with intense determination, she announces to her grown up sons that she is a lesbian and will now be embarking on a more authentic life. Her sons are scandalised. Despite the fact that her youngest son is gay himself (and slightly hurt that his apparently supportive mother had never thought to share her own conflicted sexuality with him), the other two cannot get their heads around it and assume their mother has had some kind of mental breakdown.

Meanwhile, Apple whose life has been far less conventionally successful has been married to a wealthy but violent and abusive husband for the last five years. Praying furiously for his demise through black magic, she eventually snaps and kills him. Calling Chedeng for help, the pair dismember (in full view of the “discreet” maid) and bury the body (save for the head which Apple insists on keeping, and his penis which she can’t resist nailing to the wall and ruining the perfect crime in the process). With both their husbands out of the picture the pair decide to go on the run to look for Chedeng’s first love – a woman called Lydia for whom she had promised to return, only that was over 40 years ago.

At heart Chedeng and Apple is a story of liberation. The two women have been consistently impeded by men who prevented them from living the lives they wanted to live, trapping them within the patriarchal system of the conventional family. Chedeng, a serious and earnest woman, has prided herself in conforming so completely to the social role expected of her. A straight laced schoolteacher, she married well and kept a fine home raising three sons and supporting her husband who apparently knew she was gay and just accepted it. With her children grown and her obligation to the man she married at an end, she finally feels herself free to be her true self. Apple meanwhile has had the opposite experience in a series of unfulfilling relationships with useless men on whom she blames (rightly or otherwise) her inability to pursue her dreams of becoming an actress. Finally ending up in an abusive but economically comfortable relationship, she eventually has no choice but to free herself through violent means.

A pervasive sense of melancholy haunts the film as it becomes clear how much Chedeng has suffered in sacrificing her authentic self to live the life society expected of her. Lydia, the lost love of her youth, was braver – she dreamt of escaping to an island for a simple fisherman’s life in which she and the woman she loved could perhaps live together wanting little more than each other’s company. Chedeng, conventional as she is, could not imagine it and, though she vowed to return and reclaim her love after going to the city, she has waited 40 years and fears it may be too late.

Yet the resolution to her problems isn’t found in romance but in the depth of the friendship she shares with the loose cannon that his Apple – a woman her total opposite who follows her desires to destruction and freely speaks her mind little caring what anyone else may think about it. The spiky banter between the two women has an authentic, lived-in quality that brings a degree of realism to the often absurd adventure and proves a comedic counterpoint to the heaviness of the issues. Warm and oddly hopeful for its aged protagonists, if lamenting that they had to wait so long to achieve their “freedom”, Chedeng and Apple is at once a fierce condemnation of an oppressive, misogynistic society and a joyful celebration of friendship and liberation.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed.

Lav Diaz’s auteurist break through, Batang West Side is among his more accessible efforts despite its daunting (if “concise” by later standards) five hour running time. Ostensibly moving away from the director’s beloved Philippines, this noir inflected tale apes a police procedural as New Jersey based Filipino cop Mijares (Joel Torre) investigates the murder of a young countryman but is forced to face his own darkness in the process. Diaspora, homeland and nationhood fight it out among those who’ve sought brighter futures overseas but for this collection of young Filipinos abroad all they’ve found is more of home, pursued by ghosts which can never be outrun. These young people muse on ways to save the Philippines even as they’ve seemingly abandoned it but for the central pair of lost souls at its centre, a young one and an old one, abandonment is the wound which can never be healed. If

If

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.

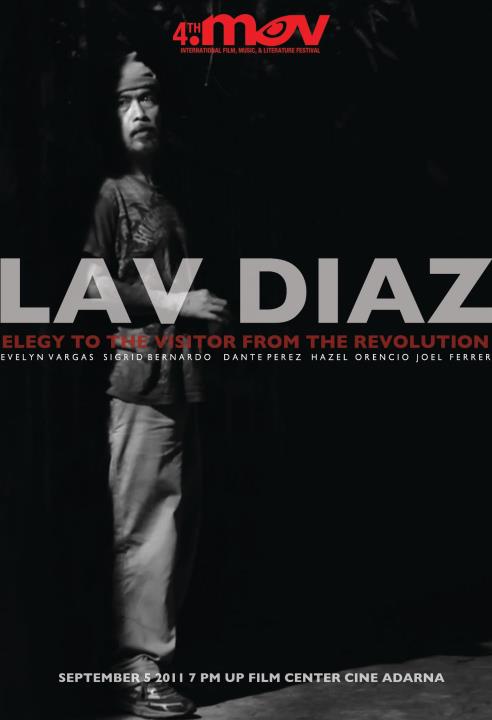

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence. Lav Diaz is many things but he’s not especially known for his brevity. Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution (Elehiya Sa Dumalaw Mula Sa Himagsikan) is something of a departure in that regard as it runs a scant eighty minutes but is, nevertheless, imbued with the director’s constant themes of loss, melancholy and despair conveyed across a tripartite structure peopled by three very different yet interconnected sets of characters. To say “only” eighty minutes long, yet Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution first began as a one minute short, intended to form a part of Nikalexis.MOV – an omnibus dedicated to the memory of film critics Alexis Tioseco and Nika Bohinc tragically killed during a home invasion. Diaz’ film, however, outgrew its origins to become a stand alone feature in its own right.

Lav Diaz is many things but he’s not especially known for his brevity. Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution (Elehiya Sa Dumalaw Mula Sa Himagsikan) is something of a departure in that regard as it runs a scant eighty minutes but is, nevertheless, imbued with the director’s constant themes of loss, melancholy and despair conveyed across a tripartite structure peopled by three very different yet interconnected sets of characters. To say “only” eighty minutes long, yet Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution first began as a one minute short, intended to form a part of Nikalexis.MOV – an omnibus dedicated to the memory of film critics Alexis Tioseco and Nika Bohinc tragically killed during a home invasion. Diaz’ film, however, outgrew its origins to become a stand alone feature in its own right. “Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope.

“Why is there so much madness and too much sorrow in the world? Is happiness just a concept? Is living just a process to measure man’s pain?” asks a key character towards the end of this eight hour film, but he might as well be speaking for the film itself as its director, Lav Diaz, delivers another long form state of the nation address. This is a ruined land peopled by ghosts, unable to come to terms with their grief and robbing themselves of their identities in an effort to circumvent their pain. Raw yet lyrical, Diaz’s lament seems wider than just for his damaged homeland as each of its sorrowful, disillusioned warriors attempts to reacquaint themselves with world devoid of hope. Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one.

Lav Diaz has never been accused of directness, but even so his 8.5hr epic, Heremias (Book 1: The Legend of the Lizard Princess) (Unang aklat: Ang alamat ng prinsesang bayawak) is a curiously symbolic piece, casting its titular hero in the role of the prophet Jeremiah, adrift in an odyssey of faith. With long sections playing out in near real time, extreme long distance shots often static in nature, and black and white photography captured on low res digital video which makes it almost impossible to detect emotional subtlety in the performances of its cast, Heremias is a challenging prospect yet an oddly hypnotic, ultimately moving one. Rather than a Maenad in a divine frenzy driven by drunkenness, lust, and hedonistic fury, a “Bacchus Lady” is a humorous nickname used for the older women who solicit men in Korean parks by euphemistically offering to sell them a bottle of Bacchus energy drink. E J-yong reteams with veteran Korean actress Youn Yuh-jung to tell the tragic story of Youn So-young, hooker with a heart of gold and now a member of the older generation permitted to slip through the cracks in the absence of familial connections.

Rather than a Maenad in a divine frenzy driven by drunkenness, lust, and hedonistic fury, a “Bacchus Lady” is a humorous nickname used for the older women who solicit men in Korean parks by euphemistically offering to sell them a bottle of Bacchus energy drink. E J-yong reteams with veteran Korean actress Youn Yuh-jung to tell the tragic story of Youn So-young, hooker with a heart of gold and now a member of the older generation permitted to slip through the cracks in the absence of familial connections.