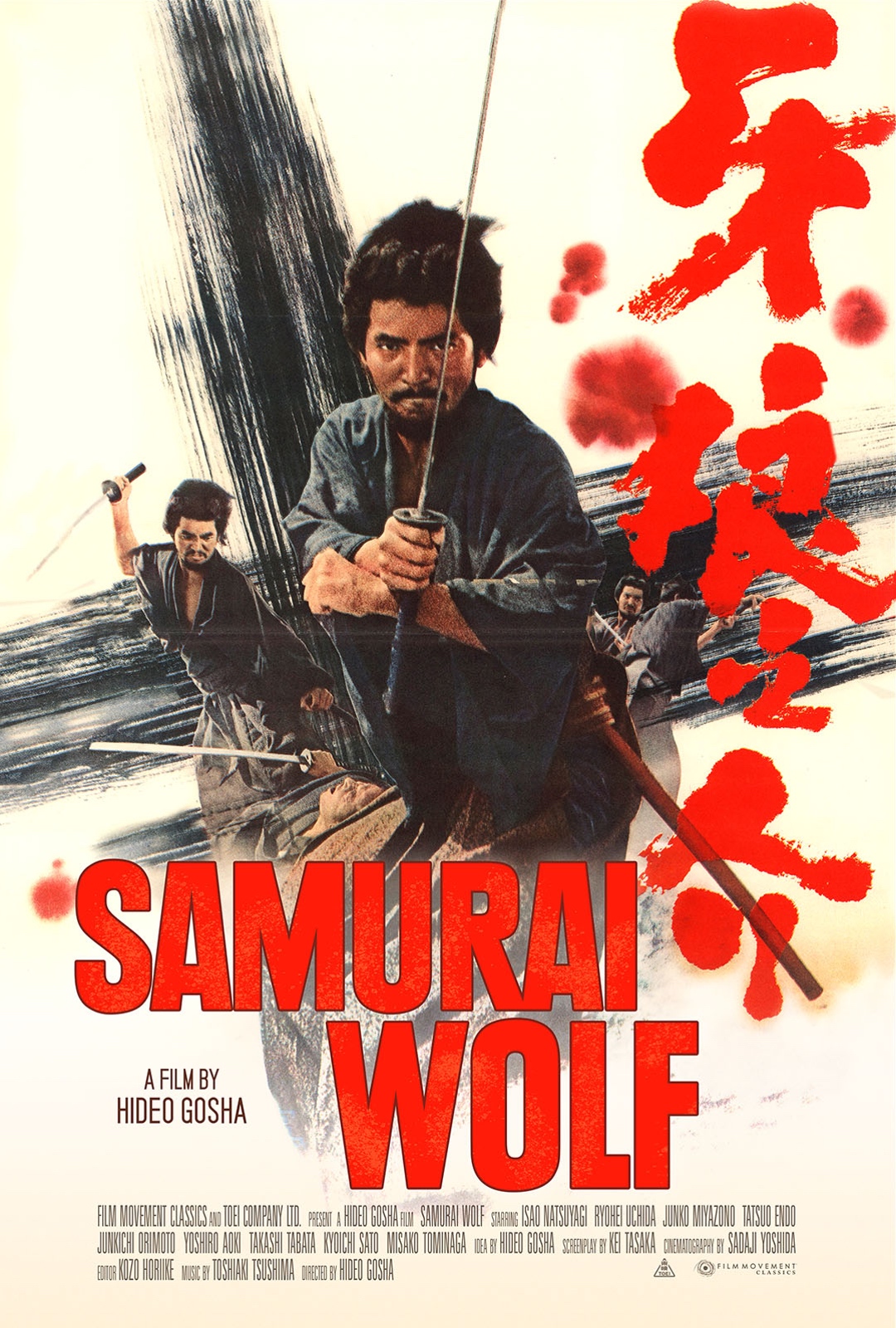

A cheerful ronin with strong moral fibre finds himself squaring off against a nihilistic assassin and a corrupt retainer/postmaster in Hideo Gosha’s new wave chambara Samurai Wolf (牙狼之介, Kiba Okaminosuke). Where many jidaigeki of the age would follow the antagonist Sanai (Ryohei Uchida), Gosha’s focusses on the figure of a man with wolfish appetites who is otherwise unaffected by the infinite corruption of the world around him and in that at least unwilling to submit himself to the dog-eat-dog mentality of late Edo-era society.

Wandering samurai Kiba Okaminosuke (Isao Natsuyagi) explains that he got his name because often he bares his fangs and is known as the Furious Wolf, yet as much as the ferocity of the opening titles might bear that image out he is not cruel or avaricious but measured and honest. After wolfing down an exorbitant amount of food prepared by an old woman at a way station, he announces that he can’t pay. The old woman panics and we wonder if he might become violent or even kill her, but Kiba simply offers to pay in kind fixing the old lady’s leaky roof and chopping a supply of wood much to her surprise and gratitude. It seems, the wolf always pays his way. While there, he witnesses a trio of bandits attack a postal cart and kill the men who were pulling it. He retrieves the bodies along with a runaway horse and takes them back to the outpost they came from but the guard there is disinterested claiming that, as they died on the road and not in the town, it’s not his business. As Kiba soon discovers, the guard is in league with a corrupt lord, Nizaemon (Tatsuo Endo), who is an official messenger for the shogun but wants to take over the public postal service which is why he’s terrorising the postmistress, Chise (Hiroko Sakuramachi), with the intention of getting his hands on the relay outpost.

There is something a little ironic in the fact that Ochise is blind while Nizaemon’s chief assassin is deaf and mute, both of them excluded from mainstream society and looking for support but finding it in opposing directions. Formerly a samurai woman, Ochise wants to hang on to the outpost because it has become her place to belong while resenting the incursion by corrupt lord Nizaemon who only wants it for the potential to control the cargo route along with raising the rates to use it to exorbitant heights. Shortly after Kiba tries to take out the assassins, a bunch of government inspectors turn up to complain about the missing merchandise while backing Chise into a corner by forcing her to accept the liability for transporting a large sum of gold coins. Kiba originally says he won’t help because he doesn’t want to risk his life for people he doesn’t even know, but of course later agrees in part on the promise of a significant return but also because he likes Chise and resents the kind of corruption men like Nizaemon represent.

On the other hand, his humanity is mirrored in his antagonist, hired gun Sanai who fetches up to help Nizaemon stop Kiba and take over the outpost. Sanai cynically tells him, that in five years’ time Kiba will be no better than he is, if he doesn’t kill him first. Kiba rejects the claim but it’s easy enough to see how someone could be corrupted by the realities of Edo-era society. Sanai later reveals that he fell in love with a samurai woman and eloped with her, a fierce taboo given the class difference between them, and later fell into his present state of nihilistic despair when she was taken from him quite literally betrayed by the social order. But Kiba seems different. He is not naive and has no expectations of human goodness yet remains cheerful and in his own way honest. When a young woman comes to him with her life savings and tells him that Sanai is the man whom she’s been waiting for to gain her revenge, he tells her to keep her money because he’s going to end up fighting him anyway. Likewise, when he realises someone he trusted has betrayed him, he tells them that he understands why they did it and bears them no ill will it’s simply the way things are only he suspects they will regret that others have died because of it. Even in his final confrontation with Sanai, he notices that his opponent is injured and ties one of his own hands to his belt to ensure it will be a fair fight.

In any case, it seems that Sanai’s morally compromised existence is about to catch up to him with several other players intent on taking his life aside from the sex worker who longed to avenge the deaths of her family murdered during a massacre of peasants killed for standing up to a cruel landowner. A female gang leader also wants revenge for the death for her boss, while the cynical madam at the local brothel offers to team up with him to steal the gold from under Nizaemon’s nose. It seems that Sanai is a man already dead, having long abandoned the lovelorn boy he was for the nihilistic existence of a wandering assassin only to be confronted with the ghosts of the unattainable past. This world is indeed rotten, but Kiba has somehow managed to rise above it embracing his wolfish appetites in more positive ways while opposing injustice wherever he finds it. Much more avant-garde than much of his later work would be, Gosha makes great use of slow motion and silence broken only by the reverberating sound of clashing swords and hints at the meaninglessness of a life of violence in an agonisingly haunting death scene in which a bloodstained man turns and falls as if the air were suddenly leaving his body. In the end all Kiba can do is turn and walk away, on to the next crisis on the highways of a lawless society.

Samurai Wolf opens at New York’s Metrograph on Dec. 26 as part of Hideo Gosha x 3

Original trailer (English subtitles)