Spoiler warning

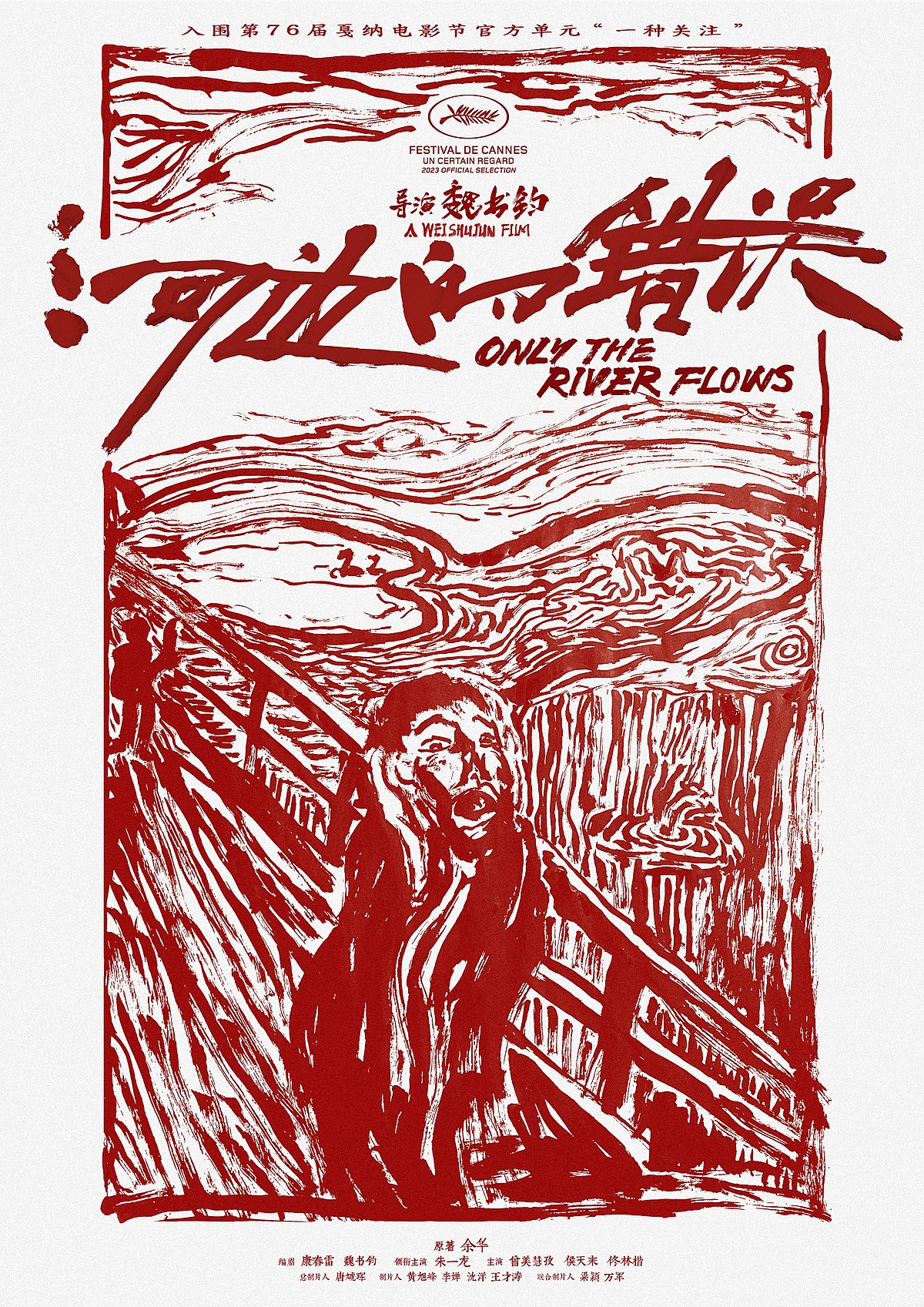

In the opening moments of Wei Shujun’s Only the River Flows (河边的错误, Hébiān de Cuòwù) children run through an abandoned building playing cops and robbers amid the ruins of a changing China. One could argue that detective Ma Zhe (Zhu Yilong) is little different from the boy who chases after the other children with a plastic toy gun in his hand and an apparent love of justice in his heart only to enter a room and find himself on the edge of precipice looking down on a digger several floors below already sweeping up the rubble while Ma and his police partner look on obliviously.

Wei fully recreates the aesthetics of sixth generation cinema, filming on grainy 16mm with a score that immediately echoes the films of the 1990s. Yet this small town in southern China is also a noirish place full of dank corridors and crumbling buildings that reflect the slow death of the old factory system along with the accompanying anxiety and displacement. Ma Zhe is also somewhat displaced. As he’s first introduced it’s as the only plainclothes detective in a room full of policemen in military uniform. His genial boss sells a message of “collective glory” that sounds somewhat outdated and is continually undermined by the fact he seems to do little himself and in fact continually instructs Ma to close the case he is working on even if he isn’t really convinced that primary suspect really is the guilty party.

Based on a novel by Yu Hua, the film’s Chinese title more accurately means “a mistake on the river bank” which could refer to the murder itself, a strange case of an apparently well liked old lady killed with a sharp object, or to an encounter Ma later has with the suspect who is referred to only as “The Madman”. Apparently adopted by the old woman, Granny Four (Cao Yang), to stave off loneliness after her husband’s death (presumably they had no children of their own) the Madman is middle-aged with some kind of learning difficulties and otherwise mute and docile never having displayed any signs of violence or volatility. Yet in his way Ma is also a “madman”, increasingly out of touch with objective reality and driven near out of his mind by his preoccupation with the case.

Pushed past his limit, Ma feels himself stalked and eventually descends into a lengthy dream sequence in which he watches his recollections projected on a cinema screen only for the negative to dissolve in flames as if it were burning a hole in his memory. His own perceptions are not reliable as confirmed by the confusion surrounding a commendation he received at a previous posting that he can no longer find, while a friend he contacts says he can’t remember him every receiving it and would have been surprised if he had as back then Ma was drinking quite heavily. Overburdened by the case, he begins drinking again and is also filled with paternal anxiety while his pregnant wife spends her time to trying to construct the image of their family by completing a jigsaw puzzle featuring a picture of a mother and child.

The couple are told, by a very unsympathetic doctor, that there is a small chance the baby may be born with a genetic abnormality that could result in cognitive impairment. While Ma leans towards an abortion (the one child policy in this era perhaps influencing his decision) his wife is determined to keep it, calling Ma a heartless man but also suggesting that the fate that has befallen him is some kind of karmic retribution. He feels the Madman in himself echoed in the fate that awaits his child and is unwilling to accept it, wondering what their life would be like with the world the way it is.

His sense of “madness” is centred in his individuality as the member of a collective and something that he finds echoed in the frustrating dead ends of his case. Several witnesses saw the body but did not report it, fearful of their own secrets being exposed. More deaths soon occur, not exactly related to the first but somehow as a result of it as if murder were catching and Ma is a point of infection bringing a hidden truth to light that accidentally exposes something others would have preferred remain private. Ma’s quest is to quell the madman within himself, as perhaps he does in once again putting on his uniform and joining the collective even if it means accepting their truth above his own or the doubts in his heart. A brief coda featuring Ma and his wife happily bathing their son in an atmosphere of warmth and comfort might suggest that order has been restored were it not for the unsettling look in the child’s eyes in the film’s final frame. Beguiling and mysterious, the film lends itself to multiple viewings in its consistently slippery realities and noirish sense of existential dread as Ma attempts to find himself amid the contradictions of ‘90s China in a land very much under construction.

Only the River Flows screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival and will be released in UK & Irish cinemas in spring 2024 courtesy of Picturehouse Entertainment.

International trailer (English subtitles)