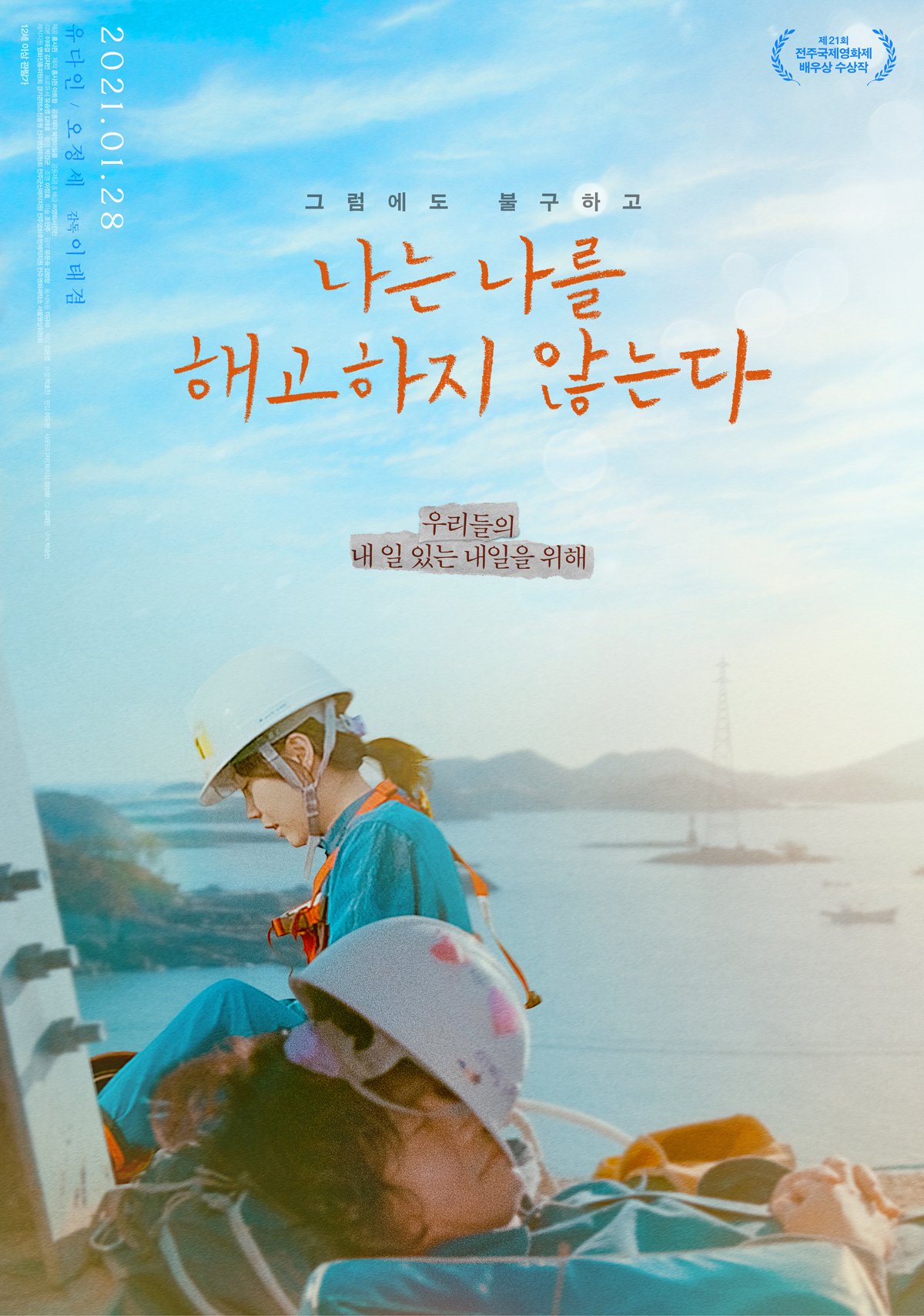

“All we asked for is not to die” a disgruntled employee reasonably explains, finally finding her voice on being confronted with the consequences of her complicity. Lee Tae-gyeom’s impassioned workplace drama I Don’t Fire Myself (나는 나를 해고하지 않는다, Naneun Nareul Haegohaji Anneunda) is the story of one woman’s path towards reclaiming agency over her life, but it’s also a subtle condemnation of rampant capitalism and the various ways entrenched social mores can set the oppressed against each other, hiding from the very ways they are each victims of the same social order.

30-ish Jeong-eun (Yoo Da-in) is a talented employee working at an electrical company but her capability only makes her a threat to her male bosses. Insisting that “it’s not about whether a woman can do the job”, her superior forces her to accept a one-year transfer to a rural electrical engineering subcontractor promising that if she works out the contract she can come back to HQ. Resolving to make the best of a bad situation Jeong-eun soon realises her new boss is not keen to have her. Her presence is an obvious inconvenience to the other three male employees who must now put a curtain up so they can change into their work clothes while resenting the unexpected intrusion into their working life. What soon becomes clear to Jeong-eun is that her new assignment is in reality just an elaborate form of “banishment room”-style constructive dismissal. Her old boss is trying to make her working life so miserable that she’ll quit on all her own.

Only, as a friend of Jeong-eun’s points out, neither of them can afford to quit because it’s so unlikely they’ll be able to find alternative employment. Jeong-eun was good at her job, but as a woman she has very little chance of career advancement and had to work twice as hard as the men just to be employed. Perhaps for these reasons, she refuses to quit resolving to stick out the year in the sticks to see what happens, but her new manager refuses to give her any work and is himself pressured by the higher ups to either push Jeong-eun towards resignation or engineer a reason to fire her. Her male colleagues only come to resent her more when it’s revealed that the substation is expected to cover her salary out of their budget which is also being reduced meaning someone will likely be out of a job. Hoping to win their trust and respect, she studies electrical engineering manuals in her off hours and offers to accompany them into the field but is quickly undone by anxiety as she looks up at the tall towers of the electricity pylons unsure how she could ever scale them.

There is something of a potent metaphor in Jeong-eun’s attempts to climb these infinite structures while the men around her laugh and try to pull her down. Latterly sympathetic colleague Seo (Oh Jung-se) snaps at her that for men like him getting fired is worse than dying and the reason she can’t climb is that for her it never will be. But Seo has in a sense miscalculated. Jeong-eun may be educated and middle class, but as she claps back to her getting fired and dying are synonyms. They are each victims of the same system, but blind to the ways they are similarly misused. Jeong-eun knows only too well the costs of getting fired, her grief over a close friend who took her own life after being forced out of her job possibly contributing to her self-destructive drinking problem. Seo meanwhile is constantly being reprimanded for falling asleep on the job, largely because he also works a series of part-time gigs to make ends meet such as manning the till in a convenience store and working as an Uber driver. As Jeong-eun discovers this dangerous, highly skilled work which is essential both for public safety and economic support pays almost nothing while the workers are also expected to provide their own protective safety gear including electric resistant overalls which run to $1000.

The inspectors sent to undermine Jeong-eun and pressure the manager harp on about how the company has already been privatised and can no longer afford “inefficiency” while continuing to exploit their employees and ride rough shod over both employment law and people’s basic rights. Jeong-eun has three months to decide if she wants to try suing them for constructive dismissal but is warned that if she does the company will retaliate and even if she wins the quality of her working life may not improve. Yet if everyone goes on thinking only of themselves the company will continue to get away with their nefarious practices

Pushed to breaking point, Jeong-eun’s epiphany comes only after a colleague is killed after being asked to fix a transmission tower in unsafe conditions while her slimy boss shows up to pressure his young daughter who can’t be more than 10 to sign away her right to proper compensation. She realises that she’s been “fired” by everyone in her life from her parents to her company, but has also been wilfully complicit in her reluctance to rock the boat believing that if you work hard and follow the rules you’ll eventually succeed even while intellectually knowing that that way of thinking is merely another tool used by the powerful to maintain their grip on power. She realises that she doesn’t need to fire herself too, seizing her own agency to mount a resistance towards the amoral venality of her ultra capitalist bosses by refusing to play by their rules anymore. A subtle yet pointed attack on the radiating effects of Korea’s notoriously poor labour law, I Don’t Fire Myself allows its educated middle-class heroine to find unexpected solidarity with a working-class labourer while ending on a note of positivity as Jeong-eun finds the courage to climb alone in the hope of bringing the light to others much like herself.

I Don’t Fire Myself streams in the US Aug. 18 to 23 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original teaser trailer (English subtitles)