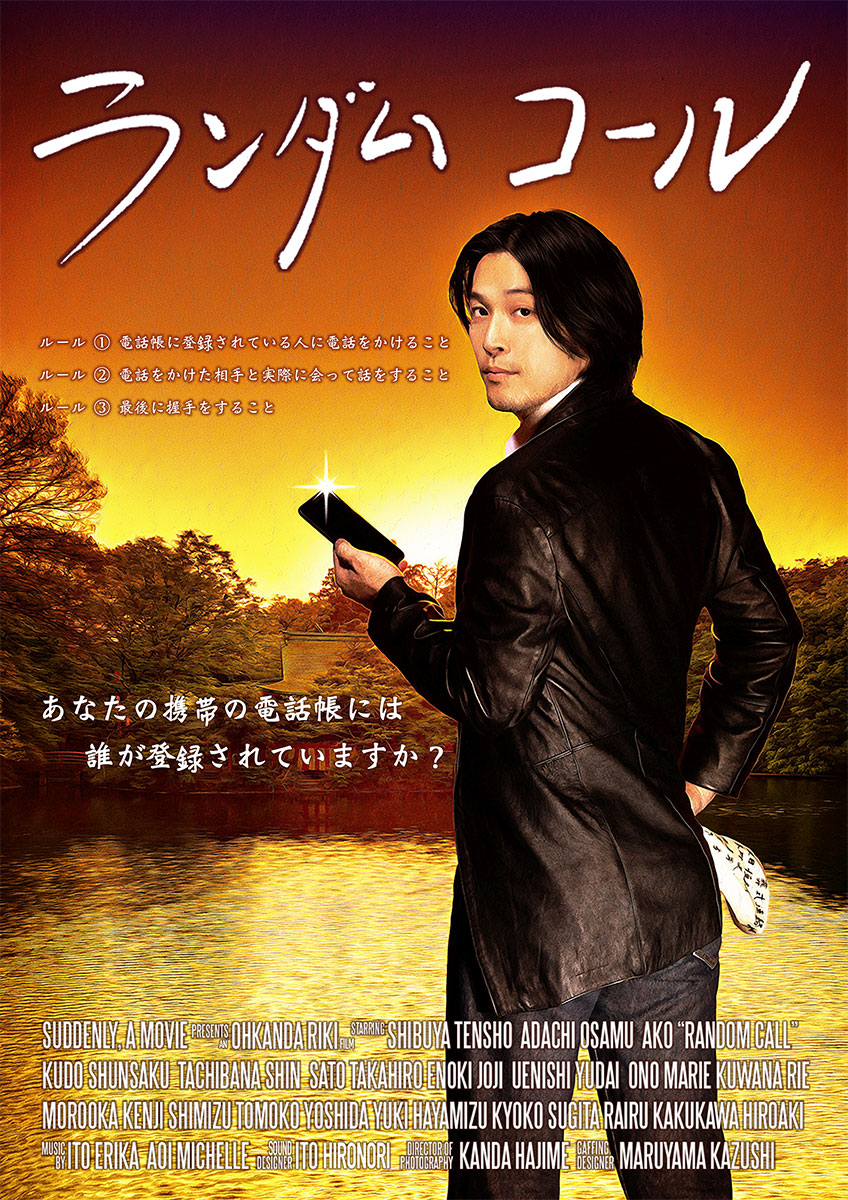

We may be more connected than ever before but now that it’s so easy to stay in touch we hardly every think of doing it. When was the last time you called someone just because with no specific reason in mind other than a desire to spend time with them? Struggling in his career and personal life, the hero of Riki Ohkanda’s heartwarming dramedy Random Call (ランダム・コール) begins to reconnect with his sense of humanity after a series of meetings with contacts from his phone selected at random each of whom teach him something about himself while reminding him that he is not alone and even if he’s not always been his best self love him anyway.

A little over 30, Ryo’s acting career has not worked out as well as he’d hoped and he’s beginning to get depressed, isolated by his internalised sense of failure while believing he’s sunk too much into his dream of becoming a successful actor to simply give up as several people including his mother advise him to do. The random call he gets from old friend Shintaro is then a kind of lifesaver reminding him he’s not been forgotten though he’s slightly bemused to discover that Shintaro claims to have no reason for wanting to meet, except he does in fact have an ulterior motive. Inspired by a recent experience in which he became ill abroad and people just helped him out of nothing other than simple human compassion, he’s embarked on the “Random Call” social experiment the results of which he hopes to turn into a book. The idea is he calls a number at random from his phone’s contact book and asks them to go for coffee making sure to shake their hand before he leaves, just checking in with old friends with no other demands or expectations. Inspired, Ryo decides to try it out for himself and encounters various reactions to the unusual project.

Perhaps that’s understandable, after all it’s natural enough that we mainly contact people when we want something from them so it’s only fair that some are annoyed or confused to discover there is no “point” to the meeting. It probably doesn’t help that the first “random” call is to a business contact, Saito, a TV producer, rather than to a friend with whom it might be more natural to meet up for a drink out of the blue. Saito is then irritated and suspicious, annoyed that Ryo is “wasting” his time assuming he’s making an awkward attempt to network but then something strange happens. He gives in to the magic of the random call and takes it at face value, accepting the warmth of an unexpected friendship and leaving a little happier than he arrived.

But then, Ryo finds himself not being entirely honest with some of his encounters painting himself as more successful than he’s actually been talking up meetings about movies after hearing of another friend’s award-winning career success and recent marriage though as we later discover the friend wasn’t being entirely honest either. Meanwhile, he cheats a little in making a not all that random call to old friend Mie after learning that she may have fallen on hard times but she tells him that her contact list is mainly full of people she’d rather not speak to so random calling’s probably not for her though she does begin to tag along on some of his adding an additional perspective to his quest for connection through which he gradually begins to realise that his inner insecurities have him led to treat people badly with the consequence that they don’t always remember him fondly.

Of course it doesn’t always work out, people don’t answer his calls, have moved away, or leave abrupt voicemails explaining they’re not lending him any money but even if it’s awkward or painful both sides gain something from the encounter emerging with a little more confidence in the knowledge that they haven’t been forgotten or else gaining a little closure to some unfinished business that allows both parties to begin moving forward. Through his various re-encounters, Ryo re-establishes a sense of connection with the world around him, encouraging and encouraged by others, and walking with a new sense of positivity into a less lonely future.

Random Call screened as part of Osaka Asian Film Festival 2022

Trailer (no subtitles)