As long as people live honest lives, eventually good things will happen to them, according to the sinister mistress at the centre of Takumi Kumashiro’s Roman Porno Woods Are Wet (女地獄 森は濡れた, Onna Jigoku: Mori wa Nureta). Perversely, she may actually believe this to be true but only in the most ironic of senses as she and her “cruel” husband enjoy incredibly happy lives together having decided to “honestly” embrace their true desires, which include things like rape, murder, and eating grapes off the corpses of their victims.

Inspired by the Marquis de Sade’s Justine and set in the Taisho era, the film begins in true gothic style as Sachiko (Hiroko Isayama), a runaway maid in flight from an accusation of having murdered her mistress, encounters Yoko (Rie Nakagawa), an upper-class lady who unexpectedly comes to her rescue in a small town. Yoko takes her back to the Western-style mansion she shares with her husband Ryunosuke (Hatsuo Yamaya) whom she describes as being incredibly cruel. Explaining that she’s been desperately lonely since her marriage at 19, Yoko begs Sachiko to stay but as her companion rather than a servant, which is another act of class transgression for which there will presumably be a price.

In any case, the atmosphere changes when Ryunosuke arrives and reveals he knows all about Sachiko’s predicament and blackmails her into helping with his schemes to rape and murder guests at the hotel he runs. He explains that he’s very wealthy and does this for kicks not out of financial necessity but nevertheless uses her to spice up his game by directly telling her to warn the guests that their lives are in danger. If she manages to get them to escape, he’ll let her go too, but of course it’s not as easy as she’d assumed it would be, especially as the first two guests she’s sent to brutally rape her. Even so, she vows to escape with them, only they are not quite clever enough to beat Ryunosuke’s game.

Out in the middle of nowhere, the mansion is a true gothic fantasy lit by candle light due to an absence of electricity because of the Depression. Ryunosuke has adapted it so that it contains a series of prison-like doors with iron bars and locks that allow him to trap Sachiko and others exactly where he wants them. He is vile and depraved, as is Yoko, though they later brand themselves as simply liberated and living “honestly” having embraced their true desires. Ryunosuke paints himself as a quiet revolutionary, asking why he should conform with rules and laws dictated by a distant authority to which he himself does not subscribe. He describes commonly held visions of morality as nothing more than a tool of social coercion designed to control the common man (which he is not), in which he may have a valid point despite the depravity of his apparently honest nature.

This aspect of Ryunosuke as an anti-social force was apparently something very much intended by Kumashiro, who was himself rebelling against a moral panic which had seen Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno line condemned under public obscenity laws. To make a point, he inserts large black blocks and lines throughout the film to mimic those sometimes demanded by the censors, though enlarged to an absurd degree and often not actually covering what they would presumably be intended to or actually drawing attention to it. In any case, what the censors objected to in this case was not apparently the sex itself but the violence which accompanies it, notably in the scenes in which blood-soaked sex continues after Yoko has shot one of the male victims she effectively raped at gunpoint.

The central part of the film is a lengthy orgy scene in which Ryunosuke has his maids whip the victims while he anally rapes them while they are forced to have sex with Yoko and Sachiko on the pretext of saving their lives. It only gets grimmer from there, though there’s a censoriousness about Sachiko’s insistence that happiness should come from correctness to counter the “happiness” that Yoko and Ryunosuke exude in their embrace of their baser desires that undercuts her role as the innocent heroine standing up to their depraved inhumanity amid the absurd interruption of a radio taiso broadcast signalling the arrival of the next unhappy guests to rock up for a less than pleasant stay at this decidedly unluxurious hotel.

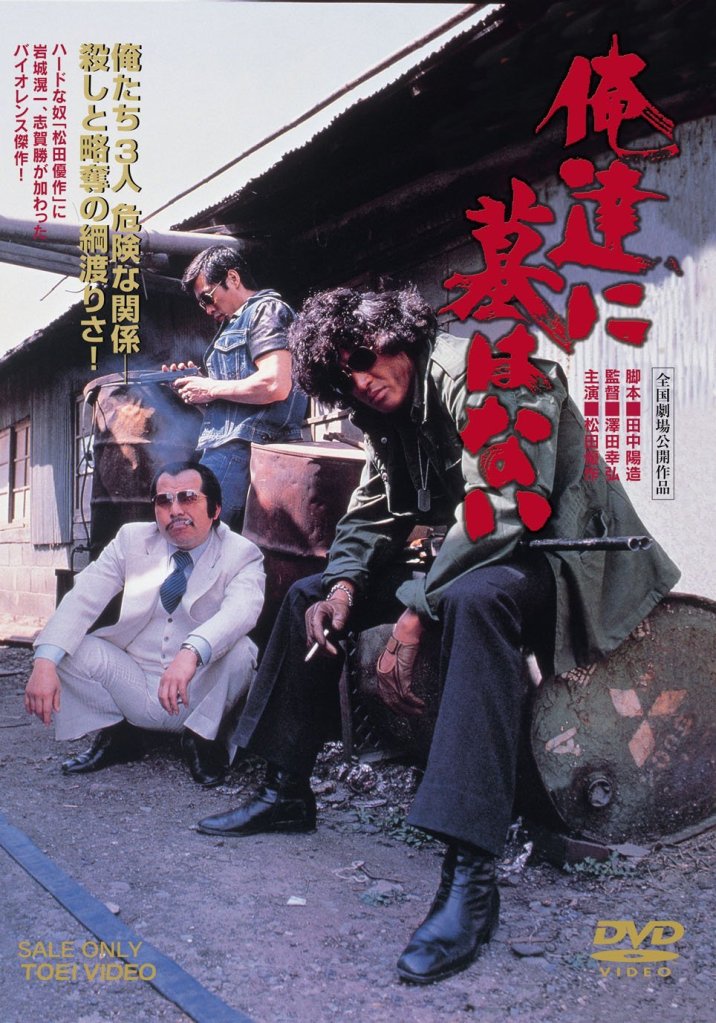

Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted.

Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted.