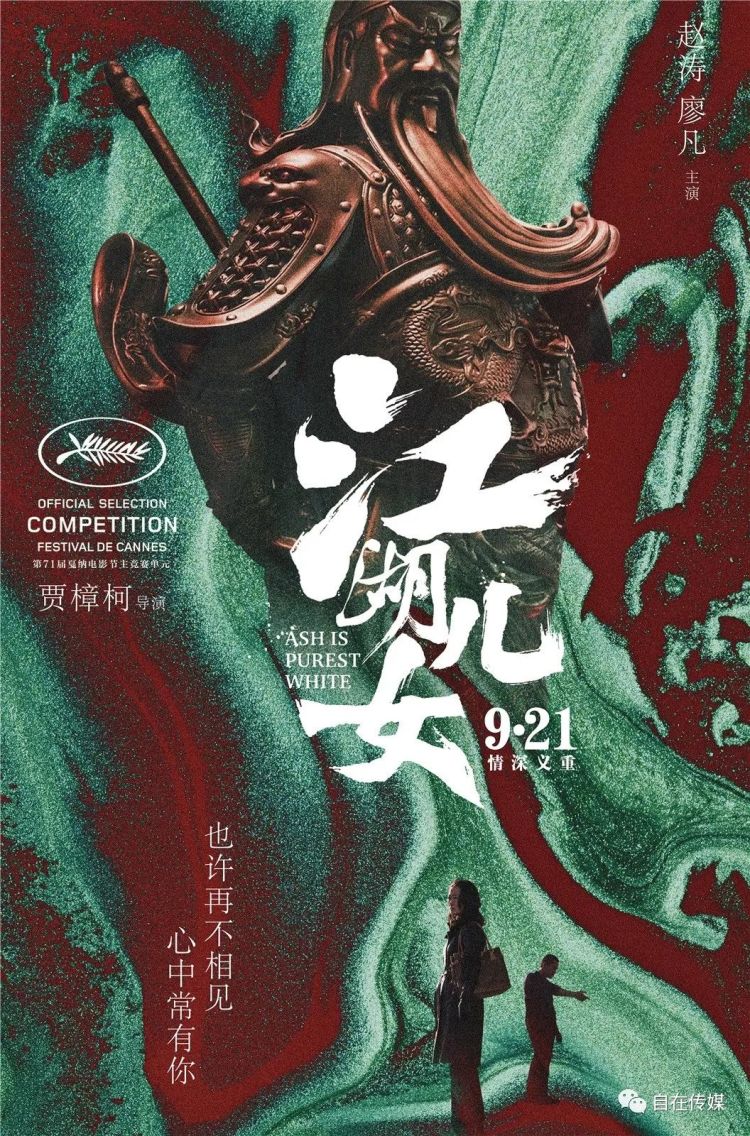

Jia Zhangke returns to the world of crime for a slice of jianghu blues in his latest chronicle of modern China through the eyes of its ordinary, downtrodden citizens. Self referential in the extreme, Ash is Purest White (江湖儿女, Jiānghú Érnǚ) is a sad story of conflicting values and missed connection as a lovelorn woman proves herself too good, too pure, and ultimately too strong for the weak willed man she can neither love nor abandon. Times change and feelings change with them. To survive is not enough but integrity comes at a heavy price in a land where everything is for sale.

Jia Zhangke returns to the world of crime for a slice of jianghu blues in his latest chronicle of modern China through the eyes of its ordinary, downtrodden citizens. Self referential in the extreme, Ash is Purest White (江湖儿女, Jiānghú Érnǚ) is a sad story of conflicting values and missed connection as a lovelorn woman proves herself too good, too pure, and ultimately too strong for the weak willed man she can neither love nor abandon. Times change and feelings change with them. To survive is not enough but integrity comes at a heavy price in a land where everything is for sale.

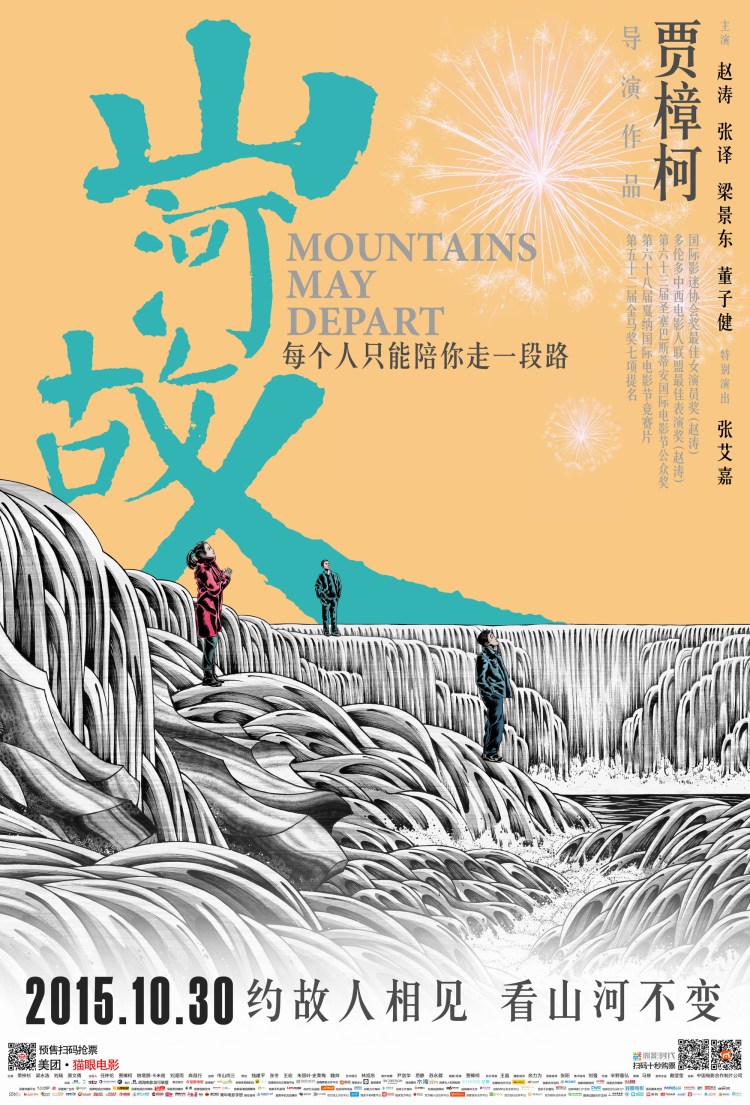

Echoing the time jumping narrative of Mountains May Depart, Jia opens in 4:3 and in 2001 as Qiao (Zhao Tao), sporting a black Cleopatra-esque haircut (the same as that worn by the identically named heroine of Jia’s own Unknown Pleasures from 2002) takes the bus into town. The first lady of the local “jianghu” underworld, Qiao is the devoted righthand woman of petty gang boss Bin (Liao Fan), enjoying the loyalty, honour, and respect of all in the slightly depressing environs of a small corner of dusty Datong. Bin is a walking monument to the idea of “jianghu” as mediated through Hong Kong action movies, swaggering around with a gun in his belt to prove that he’s the top dog in this tiny town. To live by jianghu is know that someone is always coming and when another prominent gangster is offed by young thugs, it’s not long before they come knocking on Bin’s door. Humiliatingly thrashed in the main square, Bin is only saved by a heroic intervention from Qiao who takes up his gun and fires into the air, a look of imperious authority on her face even as her eyes flicker with fear and excitement.

Qiao didn’t shoot anyone, but as the gun was illegal and she brought its presence to the notice of the police she gets into trouble anyway. A fierce devotee of the jianghu way, she refuses to give up Bin and insists the gun is hers and always has been. The gun was not hers in a real sense, and though she intends to lie in order to protect the man she loves from her mistake in firing it, spiritually speaking she and the gun are one. Having admired Bin’s skilful defusing of a petty gangster dispute without needing to use it, Qiao picks up the pistol and turns it over in her hands. The irony is, Qiao doesn’t need the gun but it completes her all the same, or at least completes the image she has of herself as an action movie heroine. Bin, however, has the gun because he doesn’t believe in himself in the same way Qiao does. He knows he’s weak and that his time is limited.

When Qiao is sent to prison for five years, she fully expects to find Bin waiting for her on the other side when she gets out. In the meantime Bin has proved true to form – he’s found himself another powerful woman to hide behind, though this time he’s chosen (or, in reality, is chosen by) one with good connections rather than fighting spirit. Bin has left the world of jianghu behind to try and make it in the rapidly developing capitalist economy, but as Qiao tells him when they finally reunite she had to live as a jianghu just to find him. Alone and friendless, betrayed by her love and disrespected by her new environment, Qiao turns to a cheeky strain of petty crime to get by – taking social revenge by attempting to blackmail random men over secret affairs, gatecrashing wedding parties for food, living by her wits on the streets and, if she’s honest, enjoying it.

Qiao is, in a sense, living in an imagined past. The frequent strains of Sally Yeh’s theme from John Woo’s seminal noir-tinged hitman drama The Killer underscore the yearning for an era of heroic bloodshed, brotherhood, and honour which never really existed outside of the movies. While Qiao grips her gun and fires in the air, Bin lights a melancholy cigarette watching Taylor Wong’s Tragic Hero, grumpily passive as always. Qiao saves Bin, more than once, but he can’t forgive her for it or reconcile himself to his own lack of resolve.

The film’s Chinese title, loosely translated as “the sons and daughters of jianghu” hints at the power of this double edged inheritance in which the archaic social codes of brotherly honour and loyalty are both barrier and bridge in an increasingly amoral society. Jia shows us a world of mine closures and forced migration, revisits the Three Gorges damn in which the past is sunk to pave way for the future, and introduces us to a modern day prospector with a big idea about UFOs. Bin, weak and opportunistic, doesn’t have the ability to ride the waves of China’s changing tides, but Qiao doesn’t have the will. Burned right through to her jianghu core, she sticks steadfastly to her code as she retreats to her spiritual home but owns her place within it even as the modern world rises up all around her. Qiao’s independence is both victory and defeat, an echo of the failed ideologies of a nation drunk on capitalism in which newfound freedom confuses and corrupts in equal measure. Nevertheless, there is something tragically romantic in Qiao’s lovelorn longing for a more passionate era in which the bonds between people still counted for something even if their demands were not always fair.

Screened as part of the 2018 BFI London Film Festival.

Short clip (English subtitles)

Full version of Sally Yeh’s theme from John Woo’s 1989 existential hitman noir The Killer

Jia Zhangke has made something of a career out of charting his nation’s history through the lives of ordinary people caught up in the business of living when everything about them is changing. Mountains May Depart (山河故人, Shānhé gùrén) isn’t the first of his films to span a comparatively wide period of time, though it is the first to venture into the “future” if only by a decade or so. Through a story of dislocation and isolation both cultural and personal, Jia has traversed the melancholy odyssey of those who grow up to discover that all the wrong choices have already been made.

Jia Zhangke has made something of a career out of charting his nation’s history through the lives of ordinary people caught up in the business of living when everything about them is changing. Mountains May Depart (山河故人, Shānhé gùrén) isn’t the first of his films to span a comparatively wide period of time, though it is the first to venture into the “future” if only by a decade or so. Through a story of dislocation and isolation both cultural and personal, Jia has traversed the melancholy odyssey of those who grow up to discover that all the wrong choices have already been made.